Ornamental bags have always been important to the native peoples of North America. Not only did they serve a practical purpose of containing important everyday items such as tobacco or fire making equipment, their beautiful designs meant that they were often regarded as a part of an individual’s ceremonial regalia.

These bags could come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, and here at the GNM Hancock we’re fortunate enough to have several examples. One of them in particular has caught my attention – an Octopus shot pouch from Alaska.

NEWHM : G025 Octopus shot pouch

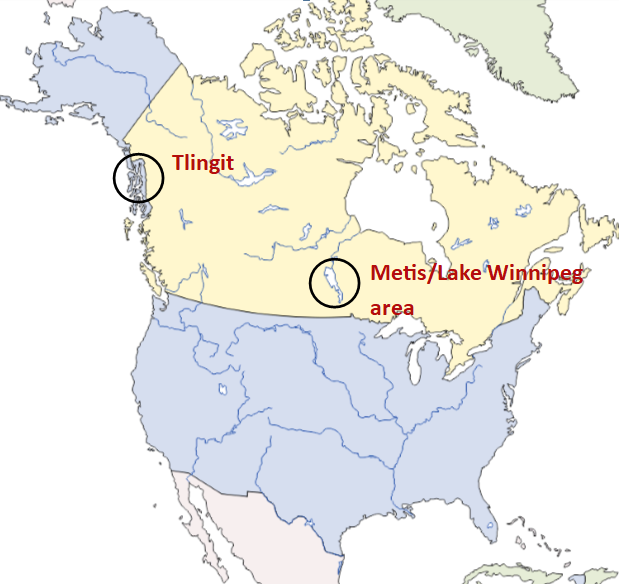

As well as looking rather stunning, they have an intriguing history as they weren’t designed with octopuses in mind at all. It’s thought that they were first developed by the Metis people who lived around the Lake Winnipeg area in Manitoba. They were based on traditional animal skin bags that the Ojibwa people made, called “Many Legs Bags” because the legs and tail of the animal were left attached to the main body of the bag. The Metis established a bag with tabbed ends to reflect this. This style of pouch was popular with both the Metis and Cree people, and over the course of the 19th century, the style travelled westward. By 1870, this tabbed bag had reached the northwest coast, and it’s here that it earned the new moniker with its introduction to the Tlingit people.

On seeing this new style of bag, the Tlingit noted its similarity to the “devilfish” or octopus that they hunted. They became known as Octopus bags to the Tlingit and as the name travelled back eastwards the new label remained.

Map showing origins of the Octopus bag and its gradual dispersion to the northwest coast

The octopus is an animal that features prominently among many northwest coast cultures. It was a crest figure among some First Nations and it also had close links to shamanism. It was also an animal that symbolised transformation due to its ability to change shape and colour. Devilfish featured in many myths and stories of the northwest coast, especially Tlingit tales of a monstrous devilfish who could devour canoes and whole villages. It’s not entirely clear why octopuses were called “devilfish”. It could be a reference to the mythological beast, or it could simply be that their appearance was considered terrifying to other animals and humans.

Either way, it makes us look at our shot pouch in a different light.

What’s also interesting with our Octopus bag is the detail – or perhaps the lack of detail involved. Octopus pouches, along with other styles of bag, would normally be embellished with exquisite beadwork, often showing floral motifs, like the ones below .

Credit: Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Credit: Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

As we can see, our bag has none of these floral decorations. If anything, the maker has done more to highlight its similarities with an actual sea creature by giving it decorative “eyes”. When examined closely, the bag shows little evidence of it ever being used- it could be that this particular Octopus pouch was made and sold as a souvenir to a European visitor or trader rather than used as any form of dancing or ceremonial regalia.

While the likes of cotton and beads were popular items to trade for, our bag also shows something extra that its maker has acquired. On close inspection we can see that the “eyes” on the bag are made up of two different types of military buttons.

The button on the left shows an eagle over an upright anchor. This is a button used in the US Navy from before the Civil War, made between the 1830s-1850s. The button on the right is harder to identify. It appears to show a floral image similar to a Tudor rose. This is a specific English emblem, and it was used on high-ranking uniform buttons in the Royal Navy in the second half of the 18th century. Both of these details make unique additions and points of interest to our curious Octopus bag.

It’s quirks like this that make our objects so fascinating to study. As curators, we can closely examine an artefact in minutiae to help reveal its hidden stories. Yet sometimes, it’s the lack of detail that can be just as telling.

This research is made possible through a Headley Fellowship with Art Fund