Hello, my name is Immy and I am researching the use of art in natural history illustration during my placement at the Great North Museum: Hancock Library. The Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) has a wonderful collection of books about the natural world that is located in the library. Many of these have beautiful illustrations with examples dating back to the 16th century.

My first blog concentrated on the use of lithography in natural history illustration and my second focussed on the natural history illustrations of Edward Lear. For my third and final blog, I have gone back to an earlier period in the illustration of the natural world and concentrated on the use of woodcuts.

We take printed books for granted these days but their production has a long and complicated history. One of the fundamental developments in printing was in the Far East around the 8th century, when the first books and prints were produced by using woodblocks to reproduce text and images. However, it was not until the 15th century that the printing press was first used in Europe to produce books by using moveable type. This innovation resulted in the ability to produce more books at a lower cost and assisted in enabling access to printed material for a wider audience. This helped to promote the distribution of knowledge in a number of fields, including natural history. Many of these early books contained what are now known to be factual errors and fanciful illustrations, yet it can be argued that in this period the availability of the content was more important than its accuracy.

From then on, artists became more and more aware of science as a medium for their work, and images began to be created for a more scientific and intellectual purpose. Illustrated publications became more widely available from the middle of the 16th century, as progress in science led to a growing need for presenting facts in a pictorial form.

Pierre Belon and Guillaume Rondelet were particularly well known zoologists of the 16th century, examples of the artwork in their books can be viewed in the NHSN’s collection at the Great North Museum: Hancock Library.

Woodcuts.

Woodcut is a printing technique that originated in China as a method of imprinting on textiles, and then later on paper. The artist carves an image directly into the surface of a block of wood using a chisel, cutting away areas that they wish not to carry ink, acting as non-printing parts. The ink is applied via a roller and an impression is made on a piece of paper. This process can be repeated a number of times, replicating a relatively sharp and bold image for each print. Woodcut was the main printing medium in Europe for book illustrations until the late 16th century, but was challenged and eventually overtaken by metal plate prints and lithography, nevertheless it still continues to be used to a lesser extent to this day.

Pierre Belon.

Pierre Belon (1517 – 1564) was a French traveller, naturalist, writer and diplomat of the 16th century. He was interested in zoology, botany and classical Antiquity, and embarked on a tour of eastern Mediterranean countries in order to identify species of plants and animals described by ancient writers. Alongside the narrative of his frequent travels, he wrote several scientific works of considerable value, such as the “Histoire naturelle des estranges poissons” which was published in 1551 and was mainly devoted to a discussion of the dolphin and included the earliest known illustration of a great white shark. His text was one of the first of its time to be based on direct observation and original drawings, and therefore gained the reputation of being a foremost body of work in the natural history field.

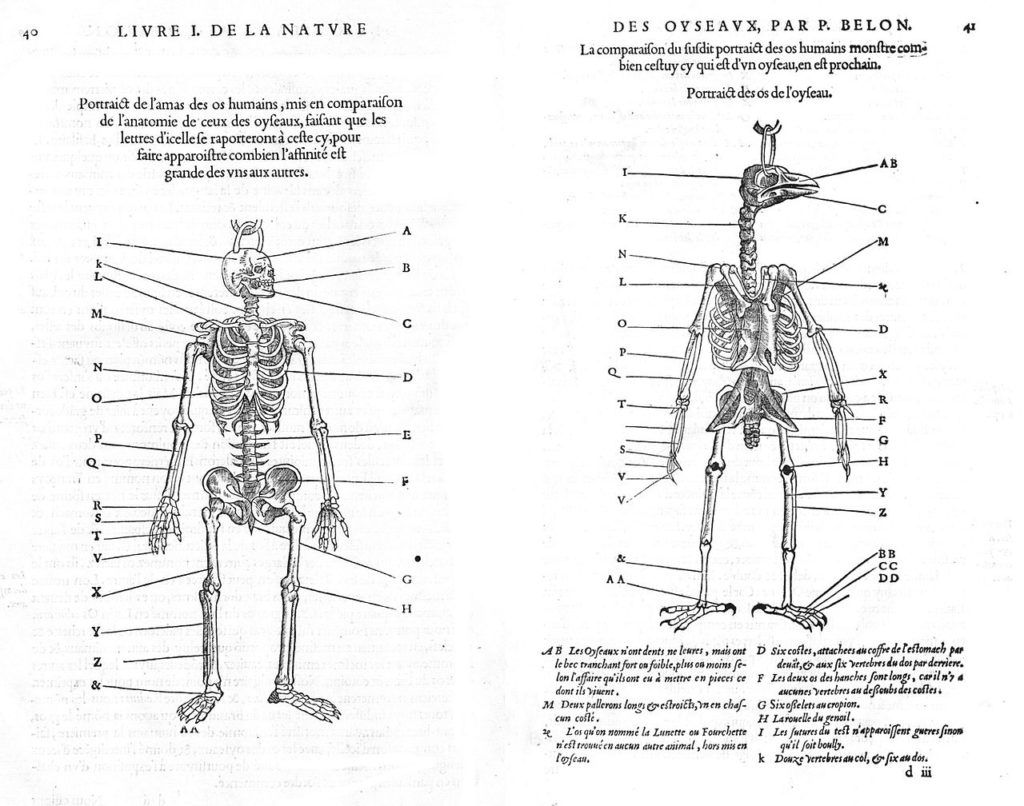

Another publication of his was the ”L’Histoire de la nature des oyseaux”, published in 1555, in which he included two figures comparing the skeleton of a human and a skeleton of a bird that is believed to be one of the earliest ideas on the variances in the anatomy of different species.

This volume contains 161 woodcuts, 158 of which were large images of birds, many of which were taken from actual specimens making the prints extremely rare for this period. A first edition of this book is included in the NHSN Library.

Guillaume Rondelet.

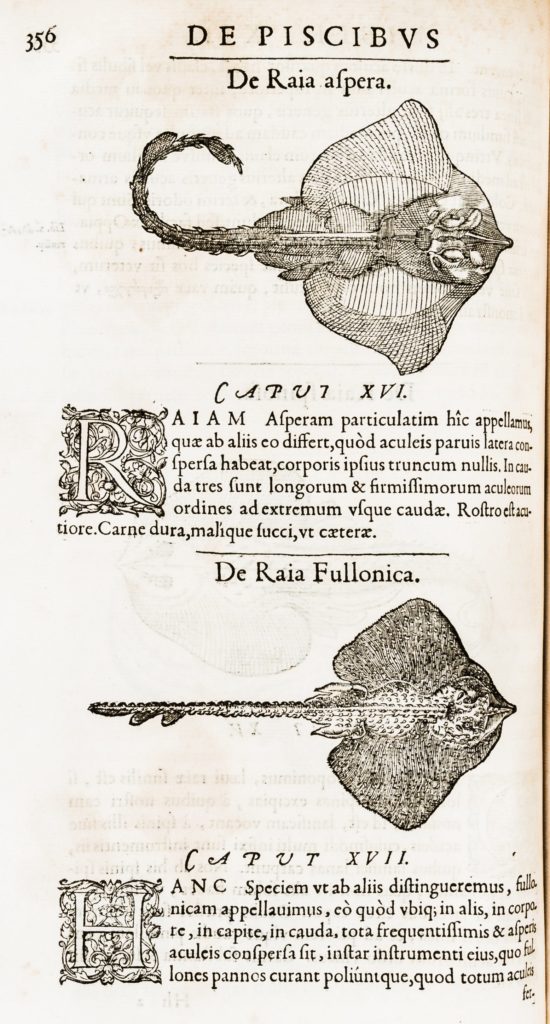

Guillaume Rondelet, (1507 – 1566) who had links to Belon, was renowned for being a naturalist with a specific interest in botany and zoology. He devoted two years of his life to the writing of a great proposition on marine animals, titled “Libri de piscibus marinis in quibus verae piscum effigies expressae sunt”, published in 1554 which earned him the title of ‘the grandfather of ichthyology’. It covered all aquatic animals, making no distinction between fish and marine mammals, and debated the question of whether fresh water creatures could potentially live in marine environments and vice versa.

He dissected and illustrated numerous creatures from his own first-hand observations, one of the most important being his anatomical drawing of a sea urchin, which is believed to be one of the earliest depictions of an invertebrate.

He dissected many specimens himself, including species as large as small whales, demonstrating his deep fascination for the subject. The book was used as a standard reference work for many years prior to its publication and was translated into French four years later.

In my opinion, I think that both of these artists succeeded in the world of natural illustration due to their shared desire to personally observe the specimens that they studied. This provided them with the advantage of imbuing a direct feeling of life to their prints. Although the artwork in these earlier publications obviously does not measure up to some of the zoological artists I have mentioned in my previous blogs, such as Edward Lear, one has to be reminded of the different era they were produced in and the limited knowledge available to the naturalists at the time. Both men made a deep and lasting impression on science, and I think they should be applauded for that.

The Great North Museum: Hancock Library is free to use and is open to everyone.

Further information about the library can be found at https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives

One Response to The Art of Nature Part 3 – Illustrations of the 16th Century. A guest blog by Immy Mobley.