Unlocking Our Sound Heritage – from a placement student’s point of view

“Real life doesn’t always sound as it should”

(Roshani Chokshi, Aru Shah and the End of Time)

We are so used to being told stories. Even real life is turned into tales of heroes and villains and happy or sad endings through books, films and lyrics. Oral history traditions are often associated with sitting around a campfire at night entertaining, scaring and inspiring each other. Sound in all shapes and forms are part of our intangible heritage, and in its honour the British Library is currently leading a nationwide project, ‘Unlocking Our Sound Heritage’. Through musical performances, literature and poetry to wildlife sounds, oral histories and more, we are allowed front row seats to first-hand information on historical events. For the participants being recorded, these events are known simply as life. As mentioned in a previous blog post, the aim of this project is to digitally preserve sound recordings and make history accessible to the public. Each recording shares something unique about the local history of the areas they are from, which in this case is Tyne and Wear in the North East of England.

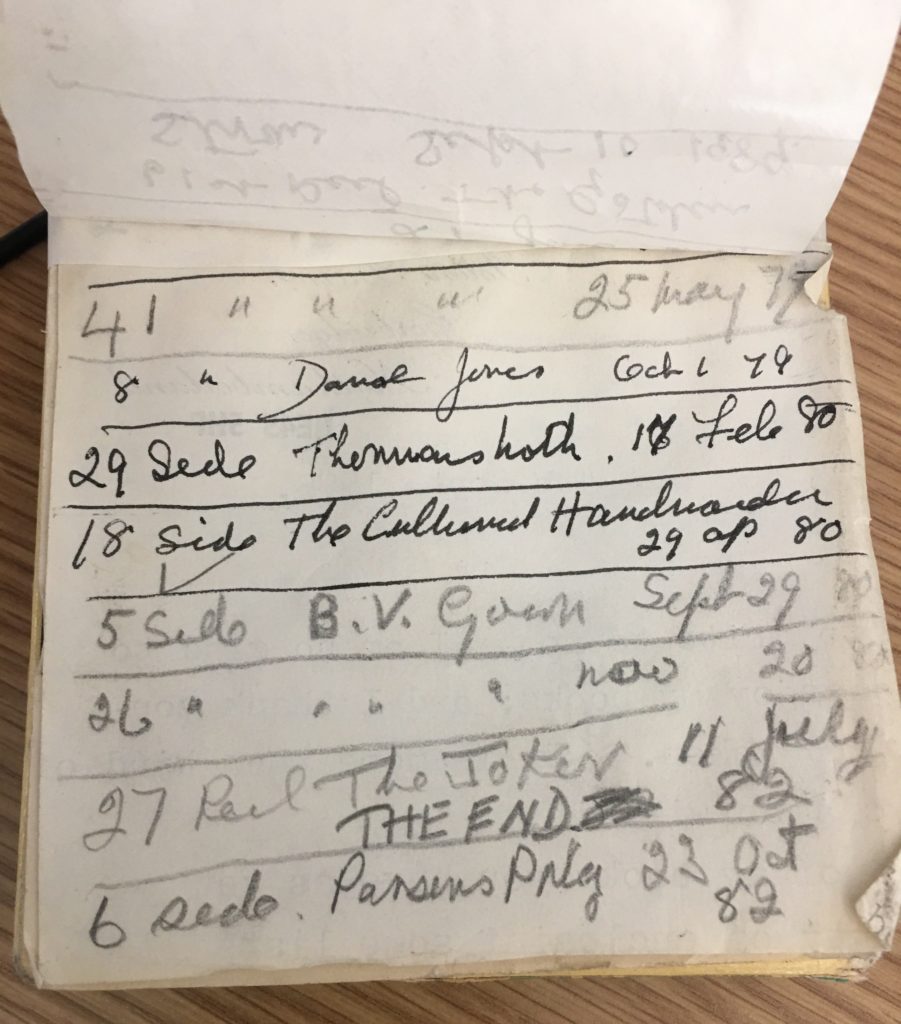

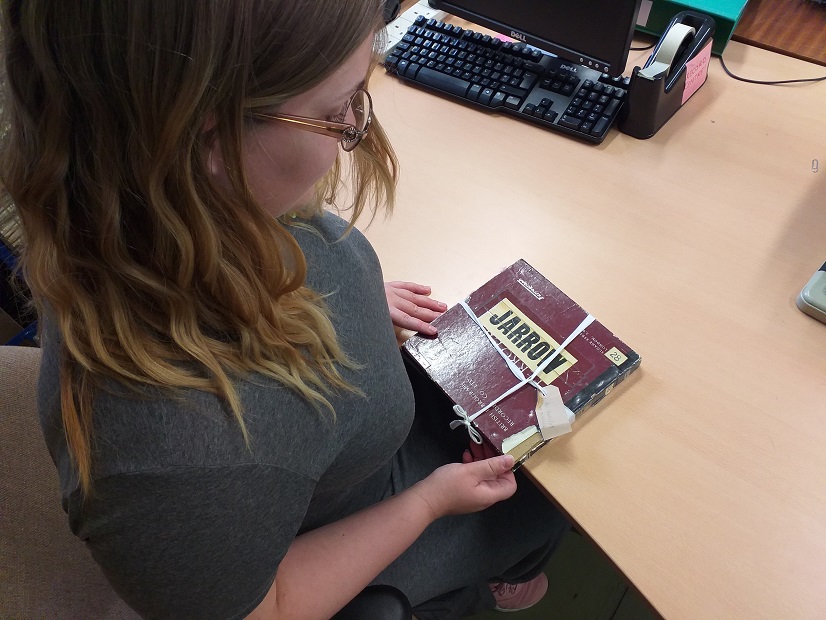

Notes on paper from a tape box which belonged to

Catherine Cookson

There is a distinct difference between listening to people sharing their first-hand experiences of the World Wars than reading about said experiences in a book. Imagine being afraid to turn on the lights at night because you cannot afford curtains and there is a nationwide blackout due to bomb threats. Imagine poverty during and after the wars being so severe that food has to be rationed and there are no jobs available, leading to a heavy drinking culture and an increase in diseases and death. It was seen as a luxury being able to rent a room in a house, let alone a whole flat, and official parish funds were established to provide families with shoes and clothing for their children. Now think about the fact that this is actually going on in several parts of the world, today. Listening to authentic accounts of people’s experiences certainly makes you think differently about the world. About history. And even about yourself.

This post was off to a bit of a dark start, but these historic accounts also make you fall in love with the country, its people and its history again. You get to relive the romanticism you are used to finding in books and films. There are stories of families growing their own produce in back gardens, keeping hens and pigeons, neighbourhood communities helping each other out, children playing in the streets and families playing the piano in the evenings, accompanied by song. Imagine getting dressed in your Sunday best and going to the seaside, or perhaps even a regatta during the summer months. Or enjoying freshly baked bread in the mornings and meat from the butchers for dinner. There are stories of attending dances and falling in love. In other words, life is not a fairy tale and it is not as black and white as good or bad and happy or sad. And what better way to learn than being handed down information from the people experiencing them?

The part I have played in the ‘Unlocking Our Heritage Sound’ project is to listen to oral history interviews of people from the local area talking about their work, family lives and experiences and cataloguing the information to appropriate British Library standards. The end goal is to make the stories accessible to the public. I have learnt more than I ever expected about working at shipyards during the 20th century – the long working hours and the great friendships formed there. I have learnt about the incredibly hard work carried out by the women in the household: baking, cooking, bathing and washing for up to 14 people. I have learnt about the development in possibilities for women beyond staying at home. I have heard the joy in their voices as they reminisce over how happy life was back then, despite living a much tougher life. I have heard the sorrow in their voices as they remember their loved ones who have passed away. If I can help make these stories available to the public, that is work I am proud to undertake!

Unlocking Our Sound Heritage is funded by a grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, as well as generous funding from charities and individuals.