In this masterpiece painting, style and subject are completely united, with the jagged fragmentation of the face, thick black lines and harsh colours expressing the woman’s agonised grief. Weeping Woman is part of Picasso’s emotional response to the bombing of civilians in the city of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), a raid ordered by the Nationalist leader General Franco.

The woman holds a handkerchief clenched in her hand, and its white colour extends over part of her face in a kind of shattered heart shape. The sharp points below her eyes direct our attention to their pupils, which reveal what’s perhaps the distorted reflection or memory of the planes dropping bombs. Looking at the whiteness of her face, it’s as if we can see through to the skull beneath, bringing to mind the bones of the dead of Guernica. Her image is a cry from the heart, and also from the victims of the bombed city. (You can read more about Weeping Woman on the Tate’s website here, here, and here.)

Picasso’s Guernica pictures had great impact on artists in Britain, and British artists opposed to Franco also forged other links with European counterparts. The exhibition Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War (Laing Art Gallery, to June 7th) reveals these connections as well as exploring the variety of paintings, sculpture, fund-raising prints and campaigning posters produced by British artists.

Guernica, ancient capital of the Basque region of Spain and a Republican stronghold, was bombed in April 1937 by German planes in support of Franco’s Nationalists. (The Nationalists eventually won the war against the Spanish Republican government and their supporters.) The raid targeted civilians and caused horrified reactions across Europe. This photo shows the devastated city. (There are many accounts of the bombing, including here, here and here.)

Guernica, ancient capital of the Basque region of Spain and a Republican stronghold, was bombed in April 1937 by German planes in support of Franco’s Nationalists. (The Nationalists eventually won the war against the Spanish Republican government and their supporters.) The raid targeted civilians and caused horrified reactions across Europe. This photo shows the devastated city. (There are many accounts of the bombing, including here, here and here.)

The British Surrealist artist Roland Penrose, who was a friend of Picasso, bought Weeping Woman soon after the picture was finished and took it to England as part of a fund-raising exhibition tour in 1938-9 to help Spanish Republican children. Weeping Woman joined Picasso’s huge canvas of Guernica (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte, Madrid) and related pictures.

The British Surrealist artist Roland Penrose, who was a friend of Picasso, bought Weeping Woman soon after the picture was finished and took it to England as part of a fund-raising exhibition tour in 1938-9 to help Spanish Republican children. Weeping Woman joined Picasso’s huge canvas of Guernica (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte, Madrid) and related pictures.

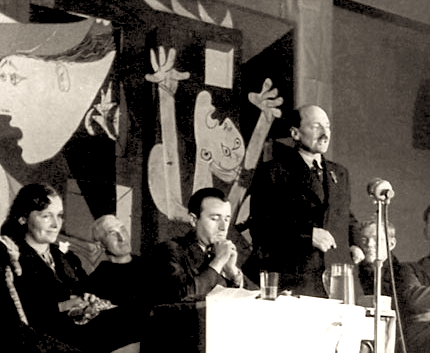

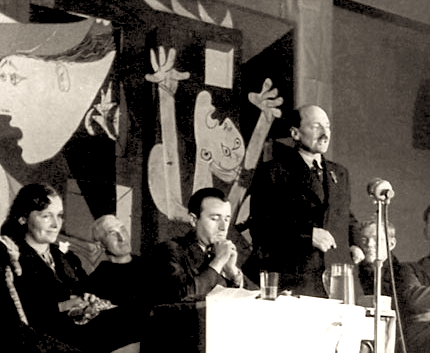

In the photo on the right, Clement Atlee, leader of the Labour Party at the time, is pictured making a speech in front of Guernica in the exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. Behind Atlee, we can see one of the distraught mothers in the painting flinging up her arms, revealing the more rounded figure style Picasso used in this picture compared with the slightly later Weeping Woman.

Picasso’s Guernica pictures helped shape several British artists’ visual responses to the war, including F.E. McWilliam. His sculpture Spanish Head condenses the grimacing mouths of suffering figures from Picasso’s paintings into a three-dimensional form that McWilliam described as a ‘complete fragment’. He was associated with the British Surrealist Group, many of whom strongly supported the Spanish Republicans. McWilliam described the Spanish Civil War as simply a case ‘of right and wrong’.

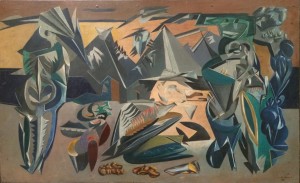

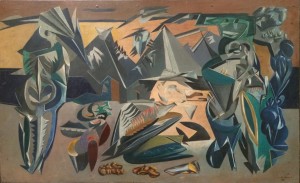

The painter Merlyn Evans refused to be part of any particular group. However, he believed that the artist’s role in uncertain times was to present ‘the aggressive instinct for power and destruction’ in a similar way to Picasso’s Guernica, which Evans had seen in the Spanish Pavilion of the International Exhibition at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937. Distressed Area (1938) was Evans’s response to the bombing of the city.

Evans described his picture as a scene of violence overlooked by an old vulture, ‘the Carrion King’ (presumably Franco), where ‘the sky burns like a furnace’. Partly bird-like, partly machine-type creatures are on the attack in an arid landscape. (As well as Picasso’s art, Evans particularly admired the machine-like figure style of Wyndham Lewis.)

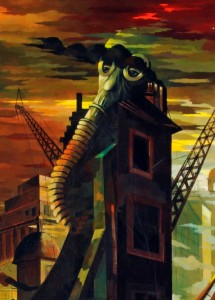

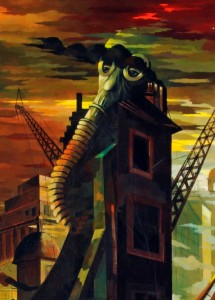

There’s also a surreal quality to Walter Nessler’s painting entitled Premonition. He painted it in 1937 after he also visited the International Exhibition in Paris to see Picasso’s painting of Guernica. In his picture, Nessler combined Guernica ruins with London landmarks like St Paul’s Cathedral (on the far left of the picture). Gas was used against the Republicans during the war, and Nessler included a giant gas mask (with eyes behind the goggles) perched on the ruins, creating an unsettling presence in the centre of the picture. Nessler’s painting proved to be an accurate prediction of the blitz of World War Two, when the area around St Paul’s was set alight by bombs.

There’s also a surreal quality to Walter Nessler’s painting entitled Premonition. He painted it in 1937 after he also visited the International Exhibition in Paris to see Picasso’s painting of Guernica. In his picture, Nessler combined Guernica ruins with London landmarks like St Paul’s Cathedral (on the far left of the picture). Gas was used against the Republicans during the war, and Nessler included a giant gas mask (with eyes behind the goggles) perched on the ruins, creating an unsettling presence in the centre of the picture. Nessler’s painting proved to be an accurate prediction of the blitz of World War Two, when the area around St Paul’s was set alight by bombs.

Nessler also owned a photograph of Picasso working on his painting of Guernica, when it was nearing completion (there are similar photographs here). The photographer was Dora Maar, who was Picasso’s mistress and was also the model for Weeping Woman. Her dramatic and emotional personality became a means of expressing Picasso’s feelings about the destruction of Guernica.

Picasso and the impact of Guernica feature in two forthcoming talks, which are part of a programme of exhibition tours and events.

Simon Martin, Artistic Director of Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, and curator of the exhibition, will be giving a talk on Saturday April 25th discussing the response of British artists, including Edward Burra, Roland Penrose and Wyndham Lewis, to the war (Laing Art Gallery function room, 2-3 pm, £5, book at the ticket desk or online).

On Thursday May 28th, Barbara Morden, art historian, will be giving a talk on ‘Picasso’s Guernica in context’ (Laing Art Gallery function room, 2-3pm, £2, book at the ticket desk).

Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War is a partnership exhibition with Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, and is accompanied by a well-illustrated book by the exhibition curator, Simon Martin.

There is a previous blog about the exhibition here.

Illustrations

Weeping Woman (1937) Oil on canvas, by Pablo Picasso ©Tate, London 2015

Clement Atlee opening the Whitechapel exhibition of ‘Guernica’ in January 1939. Photo: Marx Memorial Library, London

Ruins of Guernica, Photo: German Federal Archive, Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H25224, Guernica, Ruinen, and Wikipedia.

FE McWilliam, Spanish Head, Hoptonwood stone, The Sherwin Collection (reproduced courtesy of the FE McWilliam Estate)

Merlyn Evans (1910–73, Distressed Area, 1938, tempera on canvas over panel, Collection of Steven Rich, London (reproduced courtesy of the Merlyn Evans Estate)

Walter Nessler (1912-2002), Premonition, 1937, oil on canvas, Reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum, and the Walter Nessler Estate.