These smiling boys are pictured shortly after their arrival in Newcastle from war-torn Spain in June 1937. They are walking from their new home at St Vincent’s Roman Catholic Orphanage in Brunel Terrace in Elswick to the nearby church, accompanied by the nuns of St Vincent’s Convent. Fifteen boys were placed at the orphanage, and soon made friends with other boys there, said the Evening Chronicle, even though they didn’t speak each other’s language:

Little Tommy Armstrong, of Blaydon, who lost his parents four years ago and has been in the Orphanage since, scampered off to play on the lawn with his new chum, Syedro Arana, who was at once christened “Sed.”

There was no-one at the orphanage who could speak Spanish, but Miss Ann Rooney, who lived nearby, came to the rescue to help with translation, said the Evening Chronicle.

The Evening Chronicle story went on to say that the children had been accompanied from Spain by Miss Eastwood, who was the Spanish teacher at La Sagesse Convent School in Jesmond. She’s presumably one of the women in this photograph of the children at Central Station, being welcomed by the Mayor, John Grantham, and his wife, on June 29th 1937. The photograph is from the Mayor’s photo album in Tyne & Wear Archives collection.

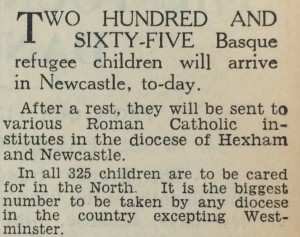

The Elswick group of boys was part of a much larger number of children who passed through Newcastle on their way to Roman Catholic orphanages in the North East, said the North Mail. The largest centre was St. Peter’s Home near Darlington, where 150 boys were housed. 100 girls went to St Mary’s Orphanage at Tudhoe near Spennymoor, and another 60 girls were placed in St. Joseph’s Home, Darlington.

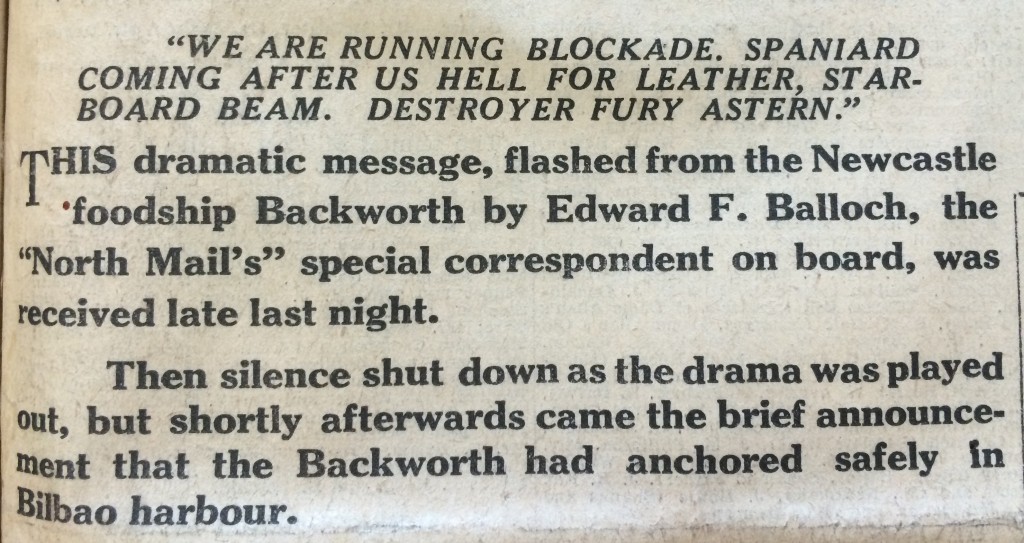

The North Mail also reported that “nearly 350 private individuals have offered refuge in their own houses for other children”. In total, 4,000 children came to Britain, landing at Southampton on the liner Habana in May before being sent to various places all around the country.

The refugees were fleeing from bombing raids that were destroying many towns and cities in Republican areas of Spain. Jarrow MP Ellen Wilkinson is shown inspecting bomb destruction in Madrid in central Spain with Clement Atlee, leader of the Labour Party, and a fellow Labour MP. It was one of 2 trips she made to Spain in 1937. Ellen Wilkinson (known as ‘Wee Ellen’ in local newspapers) also set up the national Milk for Spain scheme to help suffering civilians – people bought cardboard tokens at their local Co-op to fund the scheme. When the crisis in the Basque region occurred in northern Spain, she spoke in Parliament for help for refugees, and was involved in fund-raising campaigns in the North East to care for them.

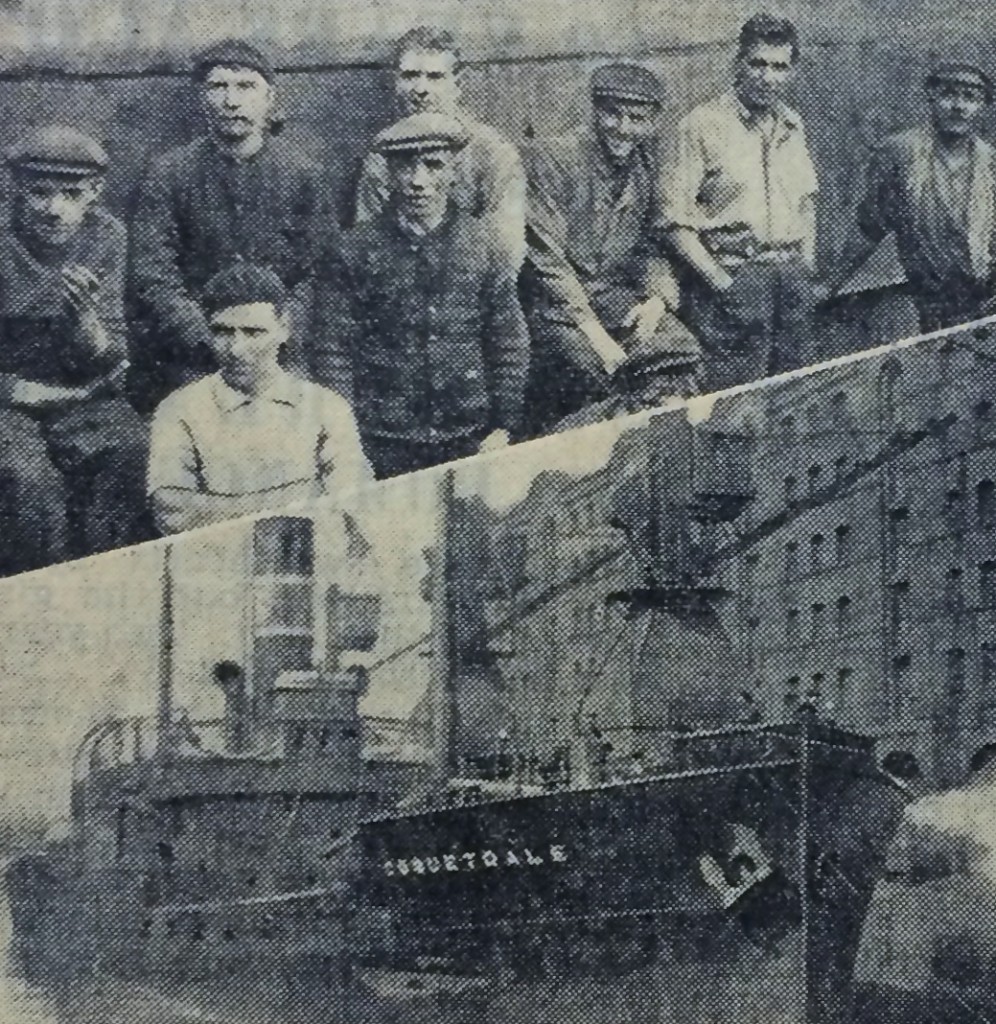

In this North Mail photo, Basque brothers Angel and Julio Perez are pictured at Tynemouth in July 1937 with Commander C. F. Barnett, a Spanish-speaking refugee worker. He had accompanied a group of 20 boys, aged 8 to 12 years, on their journey from Southampton. The Shields Weekly News commented, “The death and destruction which they have witnessed at such a young age is appalling”. These children were looked after by Mrs Nell Badsey, secretary of the local Spanish Aid Committee, and a Spanish teacher, Carmen Gil, who had travelled with the boys. Initially, there was some opposition from Tynemouth residents to the prospect of a refugee hostel in Percy Park, though that seems to have fairly quickly died away.

In this North Mail photo, Basque brothers Angel and Julio Perez are pictured at Tynemouth in July 1937 with Commander C. F. Barnett, a Spanish-speaking refugee worker. He had accompanied a group of 20 boys, aged 8 to 12 years, on their journey from Southampton. The Shields Weekly News commented, “The death and destruction which they have witnessed at such a young age is appalling”. These children were looked after by Mrs Nell Badsey, secretary of the local Spanish Aid Committee, and a Spanish teacher, Carmen Gil, who had travelled with the boys. Initially, there was some opposition from Tynemouth residents to the prospect of a refugee hostel in Percy Park, though that seems to have fairly quickly died away.

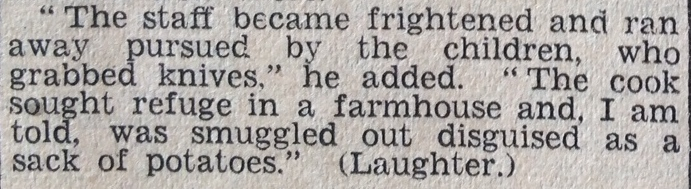

Elsewhere, there were some problems. An alarming-sounding clash took place at Scarborough, though Mr D. H. Thomson of the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief said at a meeting that the children had been ‘considerably provoked’. He blamed over-reaction by the home’s staff for the situation escalating:

The British Government imposed the condition that the sponsors of the children had to guarantee 10 shillings a week to pay for their keep. A few people resented the fundraising collections for Basque children when they themselves were struggling. They included the Gateshead man who wrote to the Evening Chronicle of June 21st sarcastically comparing the sum the Government thought was needed to keep a Basque child with the benefit payment provided for an unemployed British man’s child :

I wonder what the Mayor [of Gateshead] and M.P.s think the unfortunate unemployed man’s child will get to eat when they receive the enormous sum of three shillings a week, and have to pay retail price for everything they want. It would be more in their favour if they would look after our own children first. Edward Smith, Gateshead.

Many of the Basque children had had traumatic experiences before arriving in England, and had left behind family who they worried about. Often no-one around them spoke Spanish, let alone Basque. Senor J. I. de Lizaso, Basque representative in England, told the North Mail that some tactless hosts in England had tried to stop the children from speaking their own Basque language. This was probably because the hosts thought that after the war the children would be returning to a Spain ruled by Franco, who would certainly not encourage Basque nationalist identity.

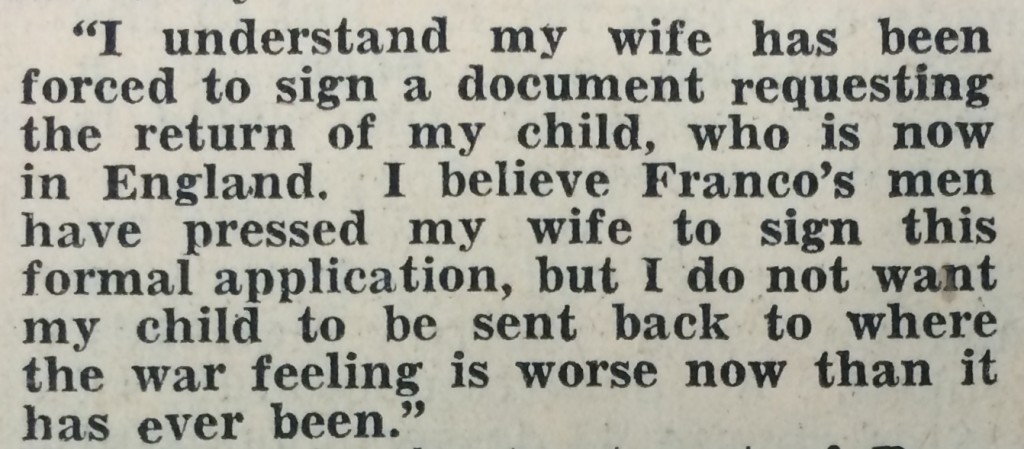

Very soon after Franco took control of the Basque region, the Nationalists called for refugee children to be returned to Spain. However, a lot of destruction had taken place and conditions were still very difficult. Senor de Lizaso, the Basque representative in Britain, told the North Mail in July of one letter in particular (among many) that he had received from a Basque father:

After the civil war finished in 1939, most of the children returned to Spain. One of the North-East boys remained as he was receiving psychological treatment in London, perhaps the result of emotional trauma he had suffered in the war. At the end of the war, the Basque Children’s Committee was wound up and funds were passed to Tyneside Social Service in Newcastle, which then had financial responsibility for the boy (letter in Tyne & Wear Archives).

Some orphans and others remained in Britain, including one of the Tynemouth boys, Angel Perez Martinez (presumably the same Angel Perez who was photographed by the North Mail). He became part of the Badsey family, and said:

If our parents could have seen their way to looking after us they would have kept us but they just could not… when we went back we realised what sacrifices they’d made and what it had been like. In the Basque country they call that period “the year of hunger”. And to my other mother, Nell Badsey, we know how much we owe.

This blog accompanies the exhibition Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War (Laing Art Gallery, to June 7th) .

**************************************************

References and Further Information

Basque Refugees Arrive in Newcastle, 29 June 1937 in the Photograph Album of Alderman John Grantham, Lord Mayor (misdated 29 July 1937 in the photo album; the same photo was reproduced in the North Mail in June), Tyne & Wear Archives, DF.GRA/5/3

Ellen Wilkinson inspecting bomb damage in Madrid, December 1937, photograph, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums collection

‘Basque Refugee Children’, Evening Chronicle, 29 June 1937 p7 & p9

North Mail, June 29 1937 p5, ’15 Basque Republican Children’

North Mail, July 22 1937 p7, “Provoked”. Basque Children’s “Flare Up”

North Mail, August 12 1937 p3, Tactless British Hosts

Basque Refugees at the Orphanage of St Mary, Tudhoe, County Durham

Don Watson and John Corcoran, ‘The Basque Refugee Children in Tynemouth’ in ‘An Inspiring Example’: The North East of England and the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939, Newcastle, 1996 (can be read at the Local Studies section, City Library).

Shields Weekly News and Angel Badsey quoted in Don Watson and John Corcoran, ‘An Inspiring Example’ 1996, as above

Letter about the winding up the Basque Children’s Committee, Tyne & Wear Archives, DF.GRA/5/3DF.WKR/28 (Eric Walker collection) (Eric Walker’s uncle Leslie Walker was very involved with care the Basque children who came to Tyneside in 1937. He married Carmen Gil, the teacher who brought them from Santander – Eric Walker biographical notes)

Basque Children of Southampton

Don Watson, “Politics and Humanitarian Aid: Basque Refugees in the North East and Cumbria During the Spanish Civil War” in North East History (annual journal of the North East Labour History Society), no.36, 2005