My name is Ashleigh Jackson. I am a History undergraduate student at Edinburgh and this summer I completed a placement with the Natural History Society of Northumbria in their archives at the Great North Museum: Hancock, looking at the effect of the Great War on the Society and its members.

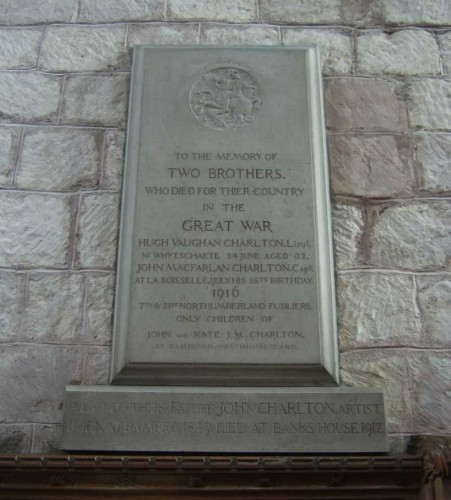

John MacFarlane Charlton and Hugh Vaughan Charlton were the sons of the renowned Northumbrian artist John Charlton (1849-1917). Their association with the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne began when John Charlton Snr moved to the North East in 1901 and applied for membership of the Society in January 1903.

Sadly, the brothers’ lives were tragically brought to an end in the ‘Great European War’ in 1916.

The Natural History Society annual report for the year 1916-1917 records: “Several of the younger members of the Society, men of promise and ability, have made the great sacrifice during the year under review. Of these, mention may be made of…Lieutenant Hugh V. Charlton, a gifted artist and naturalist, whose brush cleverly depicted bird life, and his younger brother, Captain J. M. Charlton, a good ornithologist, who though not actually a member was a frequent visitor to the Museum, to which he presented specimens from time to time“.

Lieutenant Hugh Vaughan Charlton (1884-1916)

Hugh was born in London in 1884 and moved to the North East in 1901 with his family where he was to become a skilled naturalist and artist. Before the war, Hugh followed in his father’s footsteps as an artist, focusing on birds. In 1912 his work was exhibited in the Royal Academy.

The Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) possesses original paintings by Hugh Vaughan Charlton, perhaps most interesting is his watercolour drawing of Barras Bridge from the grounds of the Hancock Museum, indicating the Charlton family’s strong connections to the museum and the society. From the archive collections at the NHSN, we have found that Hugh was elected a member of the society in April 1905.

Hugh was educated at Armstrong College in Newcastle, and this is where he joined the Officer Training Corps. He enlisted in August 1915 and left for France on 13 March 1916. Hugh was the Second Lieutenant of the 7th Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers. Hugh was struck by a bomb from a trench mortar on 24 June 1916, near Wytschaete, Belgium, just a week before the death of his brother, Captain John McFarlane Charlton. Hugh is buried at La Laiterie Military Cemetery in Ypres, Belgium, while his brother is buried in France.

The above painting of a Tawny Owl was gifted to the Natural History Society of Northumbria by Lieutenant Charlton in May 1914 before the onset of war.

The above watercolour drawing of a Herring Gull, is another piece within the archives of the NHSN more proof of the Charlton brother’s love of nature.

Finally, the watercolour drawing below depicts the grounds of the Hancock Museum and was completed in 1914. This image serves to highlight further the important connection between the Charlton brothers and the museum, and the special interest that the brothers had in both the museum and in the Natural History Society.

The Hancock Museum curator’s report for 1917-1918 discusses how the Charlton brothers had bequeathed to the museum their entire natural history collections. This included over fifty birds and mammals in mounted cases, numerous skins primarily of birds. Joseph J. Gill the acting curator during this time, paid tribute to the brothers “whose death in their country’s service has deprived natural science of two most ardent and promising votaries”.

Captain John McFarlane Charlton (1891-1916)

John McFarlane Charlton died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The 1st July 1916 also tragically marked Charlton’s 25th birthday.

Born in London in 1891, John relocated to the North East of England in 1901 with his family. In 1903, he was awarded a special commendation in the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne’s Hancock Prize competition for his essay ‘A Trip to the Farnes in 1903’. He was only 12 years old at the time but his submission showed so much skill in observing and portraying birds that one of the judges, Canon Tristram, awarded him a special prize out of his own pocket. John was deeply interested in nature, and would go on to become a promising ornithologist. It is alleged that a close relative described his taxidermy skills as rivalling those of even John Hancock, the famous Newcastle ornithologist. At school, John was secretary to the Natural History department and he was described as having ‘a wonderful knowledge of birds’. In 1910 he received a bronze medal from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, going on to write a series of articles, forging his way into the field of ornithology.

John enlisted in October 1914, soon after the beginning of the Great War. After initial training with his battalion, the 21st Northumberland Fusiliers in 1915, John and the rest of his battalion left for France in early 1916.

The Journal of British Birds paid tribute to both Charlton Brothers in the 1st September 1916 edition. The journal reveals John’s final words, which were spoken to his orderly, allegedly ‘Is that you B—? For God’s sake, push on, I’m done.’ The orderly quickly rushed to aid his captain, only to find he had died after being fatally shot in the head. On 13th November 1917 John was ‘Mentioned in Despatches’, acknowledging his sacrifice at the Somme. He had also been recommended for the Military Cross, further highlighting his distinguished role in the war.The Northumberland Fusiliers aided the attack on La Boiselle, a village near Amiens which became a crucial backdrop as part of the Battle of the Somme. The attack was ultimately a failure, and La Boiselle was captured by the Germans on 25th March 1918. John had successfully assisted in the capture of the 1st and 2nd lines in German trenches at La Boiselle, and was soon to advance on the 3rd line. As Captain, John led the advance on the morning of the 1st July 1916. At 7.30am John and his men ‘went over the top’ onto No Man’s Land despite the heavy fire from the Bavarian Infantry Regiment. Notably, the No Man’s Land at La Boiselle was particularly narrow, further complicating the mission. Along with several other men, John was stuck in a crater which narrowly shielded him from the continued firing. Later, the men were able to advance after obtaining a machine gun with which to defend themselves. However, the advance was thwarted when the gun became jammed at a crucial moment and John was shot. By midnight on the 3rd July some 200 men remained from the 21st and 22nd battalions. As a result, the brigade for while John served was pulled from the line after such heavy losses.

John is remembered at Thiepval Memorial in Northern France, as well as a memorial in Lanercost Priory, Cumbria. There is a further memorial to the two brothers in St Cuthbert’s Churchyard, Cleveland.