Holocaust Memorial Day takes place on January 27th to remember the millions of victims of the Holocaust and other genocides around the world. This blog features pictures by three artists, working in very different styles, who were part of the thriving art scene in Paris before the Nazi era wreaked devastation on Jewish and modernist artists in Europe. Jews were targeted for annihilation under Nazi dogma, and millions of other people also lost their lives due to their nationality, ethnic group, religion, political beliefs, sexual orientation, disability, or because they opposed Nazi rule. All three featured artists had migrated to Paris earlier from Russia and Eastern Europe. Their pictures are included in the current exhibition Out of Chaos at the Laing Art Gallery.

Marc Chagall painted his intensely emotional picture Apocalypse in Lilac, Fantasy in 1945 in response to the news broadcasts of the Holocaust. He was working in exile in America, where he had escaped after the German invasion of Paris in 1940. In his picture, he used traditional Christian imagery to represent the suffering of persecuted Jews. The main image shows a crucified Jewish Christ, with a prayer shawl hanging either side of his body. A Nazi soldier at the foot of the cross looms over tiny figures in scenes of mayhem and persecution.

Dreamlike imagery was an important element of Chagall’s art, and in this scene he shows an upside-down clock falling from the sky, symbolising the end of the world. Below this, a man clutches a Torah scroll, while a boat full of refugees is among the small figures further down the composition.

Dreamlike imagery was an important element of Chagall’s art, and in this scene he shows an upside-down clock falling from the sky, symbolising the end of the world. Below this, a man clutches a Torah scroll, while a boat full of refugees is among the small figures further down the composition.

Chagall worked in the La Ruche studios in Paris together with many artists from Eastern Europe, including Chaïm Soutine, who died as the result of having to flee the 1940 invasion (see previous blog Chaïm Soutine, misfit artistic genius in 1930s Paris). After the Second World War, Marc Chagall returned to France, but many others did not get that chance. Artists who lost their lives during the war included Polish-born painter Chana Kowalska.

Chana Kowalska painted her picture Shtetl in 1934 in Paris, looking back nostalgically to life in her Polish homeland. The scene shows a traditional Jewish village, a ‘shtetl’, typical of thousands across Eastern Europe before the Second World War. The arrangement of houses facing inwards around the water-pump indicates the tight-knit quality of village life. Kowalska’s painting style drew on the directness and simplicity of folk art. After the German invasion, Chana Kowalska and her husband joined the French Resistance. Tragically, both were arrested and killed.

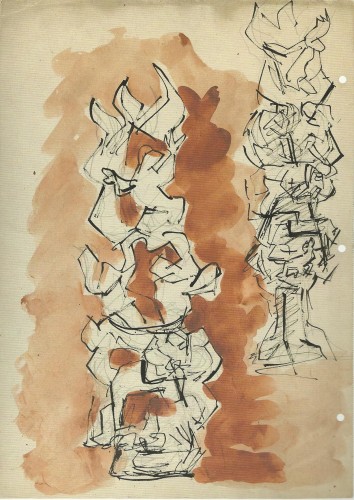

Jacques Lipchitz was one of the group of Jewish artists around Soutine and Chagall working at La Ruche studios. Lipchitz had come to Paris from a part of Russia that is now Lithuania. He also escaped to America following the German invasion, and remained there after the war. Throughout his career, he focused on spiritual themes, and his abstract watercolour represents figures reaching up eagerly towards the dove of peace. His picture was a study for a gigantic sculpture, titled Peace on Earth, which stands at Los Angeles Music Centre.

Pictures: Marc Chagall, Apocalypse in Lilac, Fantasy, 1945; Chana Kowalska, Shetl, 1934; Jacques Lipchitz, Between Heaven and Earth, about 1966: all pictures © The Artist’s Estate, Ben Uri Collection