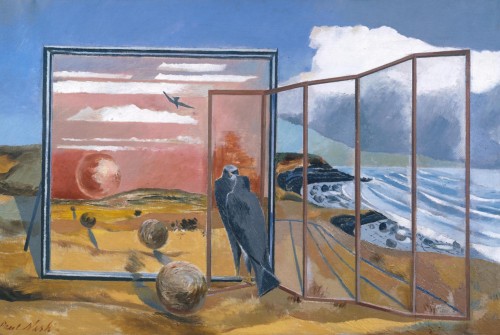

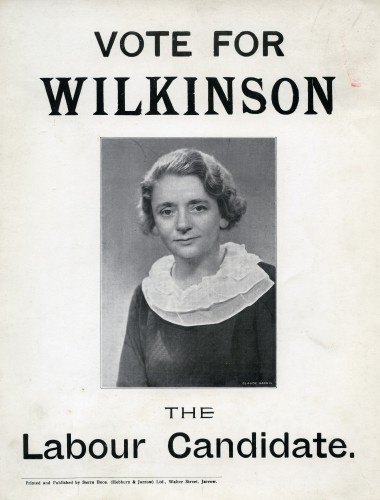

Landscape from a Dream 1936-8 by Paul Nash 1889-1946, Tate, London. Photo © Tate, London, 2016

This lovely picture, Landscape from a Dream, is a highlight of the surrealist-influenced pictures in the Paul Nash exhibition at the Laing Art Gallery, showing until 14 January. This painting is Nash’s attempt to capture the mystery and power of a dream. Its contradictory elements have aspects in common with surrealist paintings by artists such as Salvador Dali and René Magritte. The huge mirror facing us reveals an alternative reality featuring an extraordinary landscape with a huge globe in a red sky behind a line of small spheres with stalk-like shadows. Another sphere in front of the mirror creates a link between this strange land and the viewer’s space. Nash described the spheres as souls, and said that the hawk looking at its mirror image was part of the real world. (In actuality, the hawk was based on an Egyptian stone statuette that Nash owned.) Through the folding screen we see a view of the Dorset coast – Nash was fascinated by the strange forms of fossils and marine life in this area.

Nash’s emotional attachment to the English countryside was a feature of his art throughout his life. He described his feeling for landscape, saying, ‘There are places … whose relationship of parts creates a mystery, an enchantment, which cannot be analysed.’ Nash was a significant figure in the Neo-Romantic movement of the 1930s and ’40s.

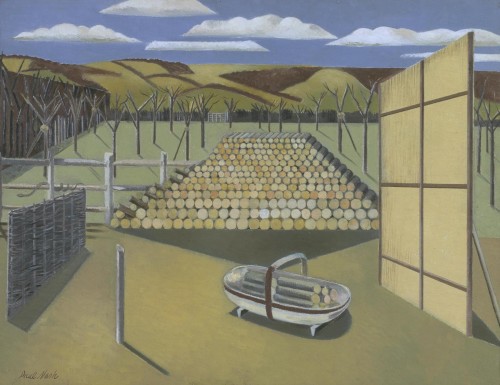

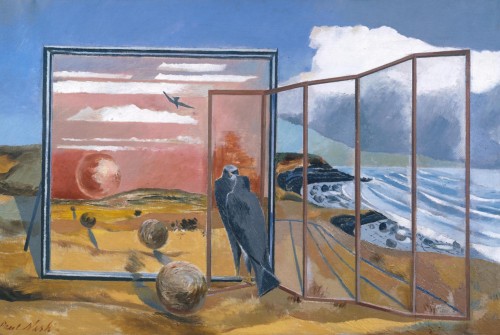

‘Landscape at Iden’ 1929 by Paul Nash 1889-1946, Tate, London Photo © Tate, London 2016

One of Nash’s special places was Iden in Sussex, where he lived for several years. His painting Landscape at Iden shows the view from his studio window. The slanting perspective and out-of-scale objects in the composition reveal the influence of the Italian surrealist Giorgio de Chirico. The unreality of the scene is increased by the weird triangular shadow of the woodpile, as well as the screen propped up like a stage-flat on the right. Nash first saw de Chirico’s pictures in London in 1928, and said it was the beginning of ‘a new vision and a new style’ for him.

Nash was haunted by seeing the battlefield carnage of the First World War, and the leafless trees and cut logs in the scene may be references to the dead soldiers. Fallen trees were common metaphors for death at the time. Also, in Nash’s personal mythology, trees had the presence of people. Looking at the picture in this frame of mind, the logs sticking out of the left side of the woodpile start to look like gun barrels. Nash also included a snake wriggling along a fence post on the left, which adds a note of menace to the apparently calm scene.

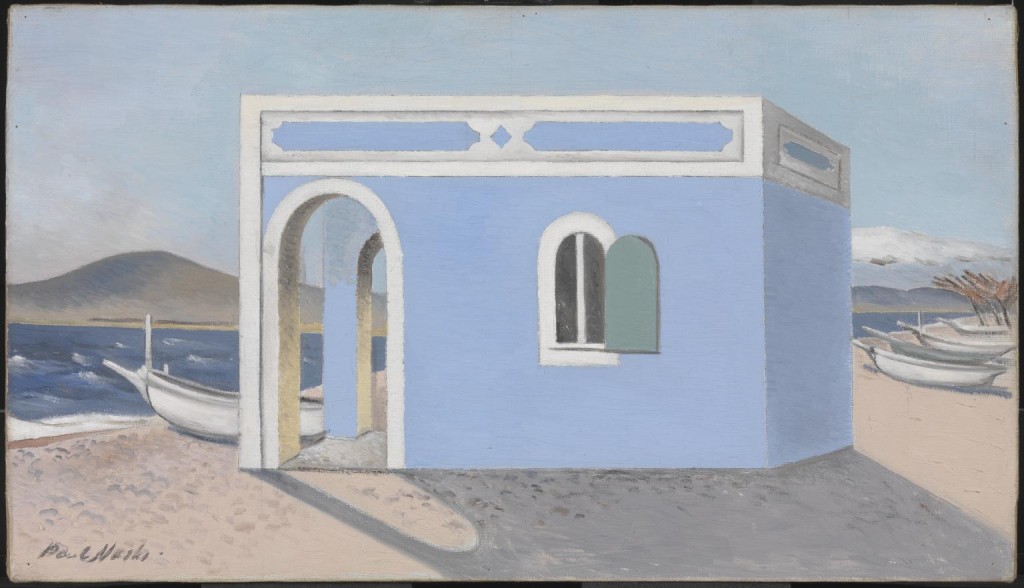

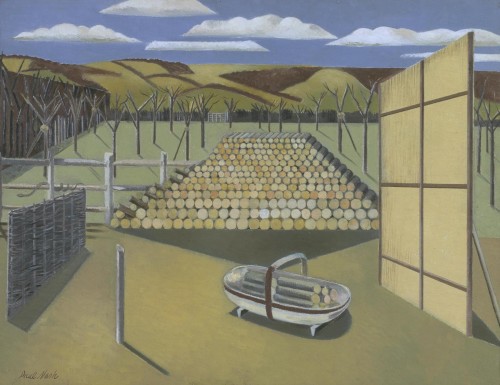

‘Blue House on the Shore’ about 1930-1 by Paul Nash 1889-1946, Tate, London. Photo © Tate, London 2016

De Chirico’s influence comes through strongly in Blue House on the Shore, where a huge, toy-like building dominates a beach (probably a view from Nash’s visit to the south of France in 1930).

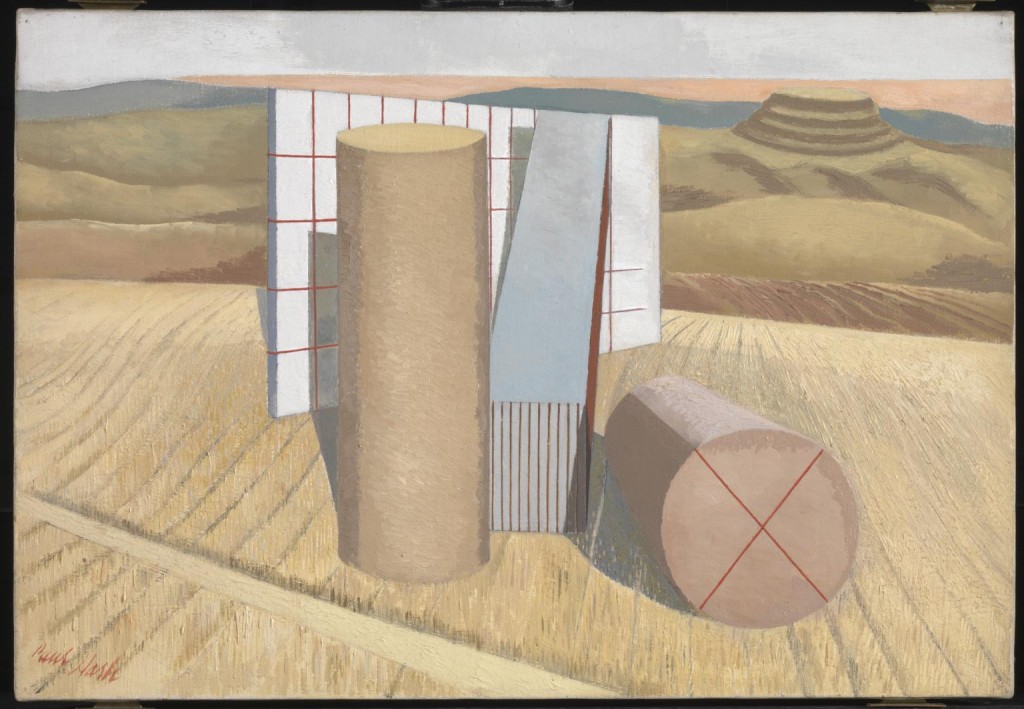

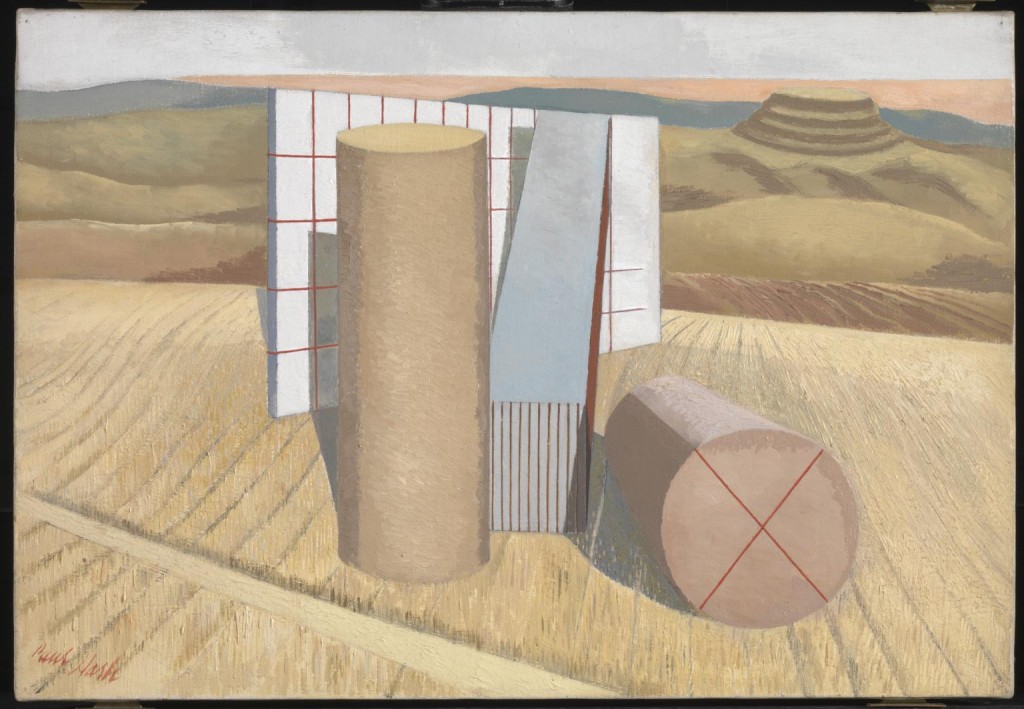

‘Equivalents for the Megaliths’ 1935 by Paul Nash 1889-1946, Tate, London. Photo © Tate, London 2016

Equivalents for the Megaliths is Nash’s reinterpretation of the standing stones at Avebury, a massive New Stone Age (Neolithic) site around 30 miles north of Stonehenge in Wiltshire. Surrealist and abstract influences both make an appearance in this picture as Nash attempts to recreate the visual surprise and mysterious presence of the huge stones (megaliths) in the landscape. These have been transformed into geometric shapes, placed incongruously on the regular lines of a stubble field after the wheat harvest. As we would expect, Nash has played with the perspective, joining the blocks in a perplexing combination.

The two large stones at the Cove, Avebury henge, Wiltshire. Photo by Jim Champion, 2008, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, GNU Free Documentation License.

![Barbury Hill Iron Age Fort, Wiltshire. Photo by Geotrekker72 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/640px-Barbury_Hill_Iron_Age_Fort1-500x375.jpg)

Barbary Castle Iron Age Fort, Wiltshire. Photo by Geotrekker72 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The stepped mound in the distance of the composition is probably Barbary Castle, an Iron Age hill fort, about 7 miles from Avebury. (During his career, Nash also often painted the Iron Age hill fort at Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire, though the trees there obscure the shape of the fort.) Nash had a deep feeling for England’s ancient heritage. He wanted to reveal ‘unseen landscapes’, and make people see familiar countryside and objects with fresh eyes.

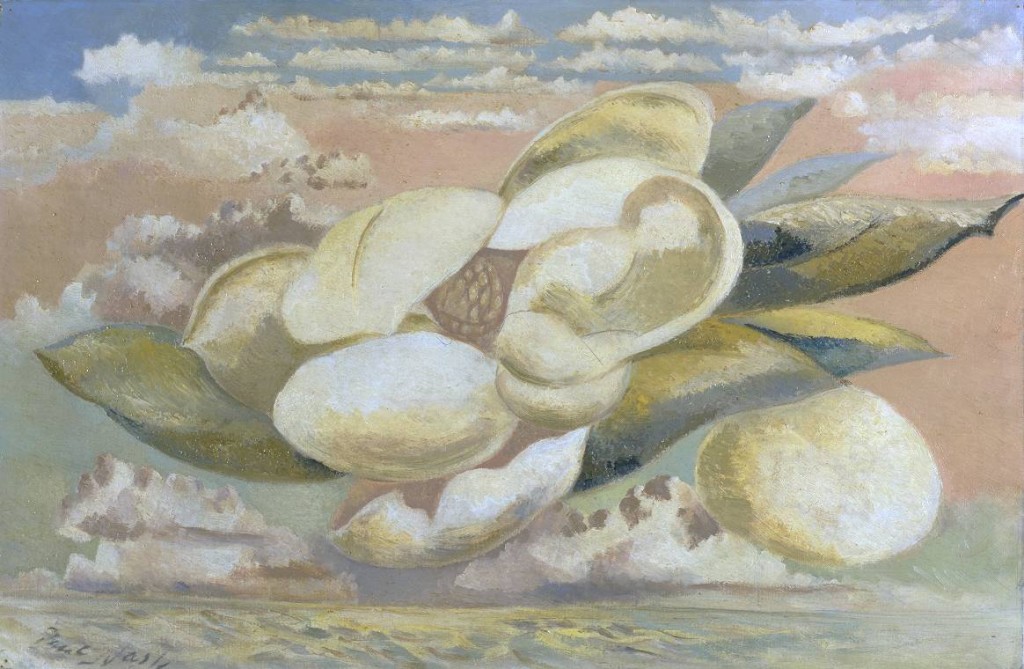

‘The nest of wild stones’ 1936 by Paul Nash 1889-1946, Tate, London. Photo © Tate, London 2016, Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

During the 1930s, Nash also explored surrealist techniques of using found objects and collage, trying to free the creative impulse of his unconscious mind. In the exhibition, there’s a fascinating group of Nash’s photographs, such as this image of The nest of wild stones, together with found objects that inspired him. There are also surrealist pieces on show by Eileen Agar, with whom Nash was working at the time.

‘Monster Field’ 1938 by Paul Nash 1889-1946 ,Tate, London. Photo © Tate, London 2016. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Nash’s imagination was also seized by ‘object personages’ that he discovered in the countryside. One of these, a fallen tree, inspired a series of photographs that he titled Monster Field.

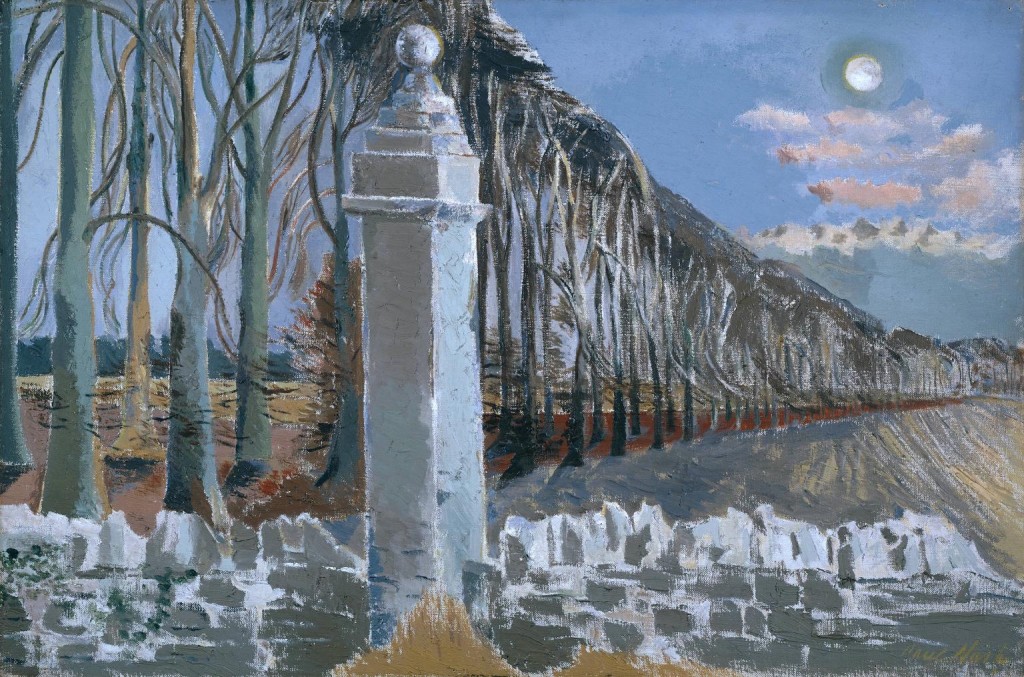

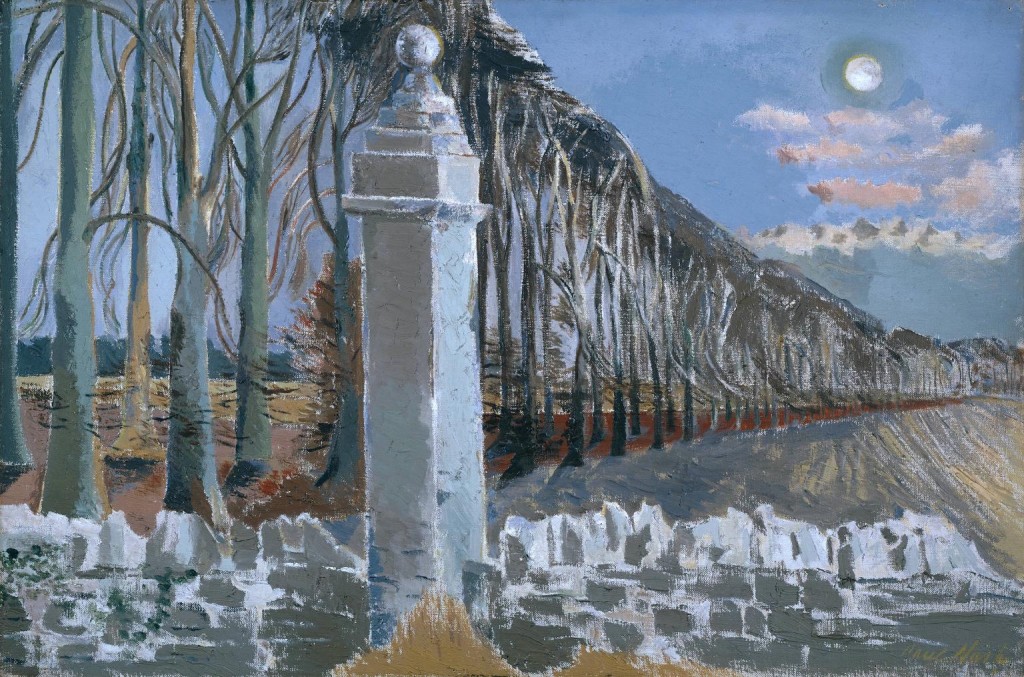

‘Pillar and Moon’ 1932-42 by Paul Nash 1889-1946, Tate, London. Photo © Tate, London 2016. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Nash began his picture of Pillar and Moon during his main surrealist phase in the 1930s, and returned to it a few years before his death. Nash said that the stone ball on the pillar was a counterpart for the cold, lifeless ball of the moon, and he created a scene that has the uncanny quality of a dream. Nash had been fascinated by the mystery of night-time scenes since early in his career. In an essay on ‘Dreams’ (a typescript in the Tate Archive) he wrote, ‘The divisions we may hold between night and day – waking world and that of the dream, reality and the other thing, do not hold. They are penetrable, they are porous, translucent, transparent; in a word they are not there.’ Like many other of his surrealist compositions, Pillar and Moon brings together several strands in his art – mystery, dreams, and an emotional identification with English landscape.

The exhibition is organised by Tate Britain in association with the Laing Art Gallery and the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts. It is on show at the Laing Art Gallery until 14 January. The Paul Nash Exhibition Guidebook is available online and through the Gallery shop, £24.99.

Paul Nash and Landscape: Events at the Laing

Wednesday 1 November, 12.30-1.15pm: Paul Nash, Cultural Landscapes and Interwar Britain, with Ysanne Holt, Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Northumbria University.

£4, students free.

Tuesday 14 November, 12.30-1.15pm: Paul Nash: Imagined Landscapes, with Emma Chambers, Curator Modern British Art, Tate, who curated the Paul Nash exhibition.

£5.

Thursday 23 November, 7-10pm: Laing by Night: Surrealism Set Loose

Experience the Laing like never before with this late event inspired by Surrealists like Paul Nash. Free your creativity with techniques the Surrealists used to access the subconscious.

£15 per person, exhibition entry included.

![ATS girls preparing to work with AA Guns, 1941 [LD & NH Regimental History collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Image-9-NEWKH_2744_11-500x394.jpg)

![Barbury Hill Iron Age Fort, Wiltshire. Photo by Geotrekker72 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/640px-Barbury_Hill_Iron_Age_Fort1-500x375.jpg)