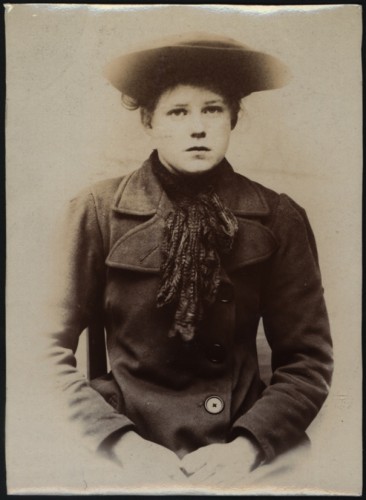

As a volunteer at Discovery Museum, I’ve been helping with some work in the TWAM online photo collection, and along the way I’ve found some great photos I’d like to share with you featuring women. Part I of this guest blog looked at the period before the First World War. In Part II, I’d like to show you just a few photos illustrating how women’s lives were affected by the Great War.

It is well known that, during the First World War, so many working-age men were called up that women had to be recruited to fill many roles in traditionally male environments for the duration of the conflict. Some roles were paid and others voluntary. Women could now find themselves in action on the Home Front as a member of the local fire brigade, a postal worker or a tram conductress, as in the photos above.

For many young women in our area, war service came in the form of munitions work.

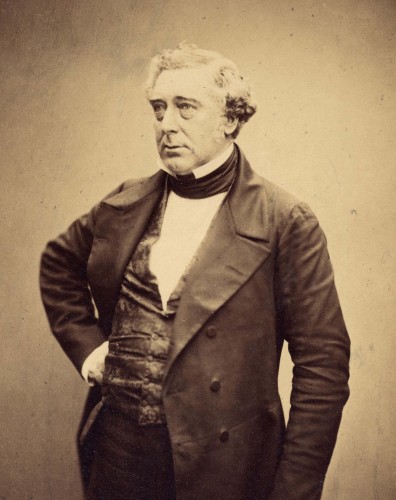

With a high concentration of industrial works along our rivers, the Tyne, Wear and Tees saw many young women enter the engineering firms to ‘do their bit’, like the munitions workers above. While many young women worked on the assembly lines, one woman, Rachel Parsons (1885 – 1956), stepped into a management role in one of our most prominent firms. Daughter of industrialist Charles Parsons and leading suffragette Katharine Parsons, Rachel Pasons grew up in a science-orientated household and was one of the first women to study Mechanical Science at Cambridge. When her brother joined the Army in World War One, she took his place on the Board of Directors of Parsons’ Marine Steam Turbine Company Works in Heaton, taking charge of the new female workforce. She also worked for the Ministry of Munitions in the area of training for women workers. After the war she went on to campaign for equal access to technical schools and colleges and for equal employment rights for women. Her life is described in more detail in David Wright’s fascinating TWAM guest blog of 2014.

This final photo is one of my favourite finds. With many young women thrown together in the novel environment of the munitions and engineering firms, the First World War brought opportunities for new social experiences too. As the existing men’s football teams disbanded with their members called up to fight, female teams began to form, mostly made up of girls now working on the engineering production lines, and women’s football matches became a popular spectator event. In the North East, 1917-18 saw the establishment of a league known as the Munitionettes Cup which was set up as a competition between women’s teams from industrial sites from the Tyne, Wear and Tees. As well as being for sport, the league was regarded as a contribution to the war effort and all games were charity fundraising events, often playing to big crowds. The strongest team by far was Blyth Spartans Munition Girls, with their star striker Bella Reay, who won the Cup in 1918.

This is the only photo of a WW1 ladies team I have found in TWAM’s collections so far – dated 1918 but with no team name given, we have no idea who these women were, whether they were a workplace team or simply a group of friends. We’d love to be able to put a name to them – can anyone help?

Janette Bell

If you’d like to see more photos from our collection, many can be viewed online using TWAM’s collections search engine. To find more pictures of people, try typing ‘man’, ‘woman’, ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ into the Theme box and see what comes up!