Cpl Ian Forsyth with his comet tank crew, September, 1944.

‘There are no extraordinary men… just extraordinary circumstances that ordinary men are forced to deal with.’

Fleet Admiral William Halsey, United States Navy

When researching this month’s blog I was drawn to the idea of ordinary people dealing with extraordinary circumstances. We see and hear examples of it almost every day. Often these days, sadly, it is ordinary people randomly caught up in terrorist attacks, but we are so interested in this concept that we contrive extraordinary situations for our entertainment and somewhat perversely call it ‘reality TV’.

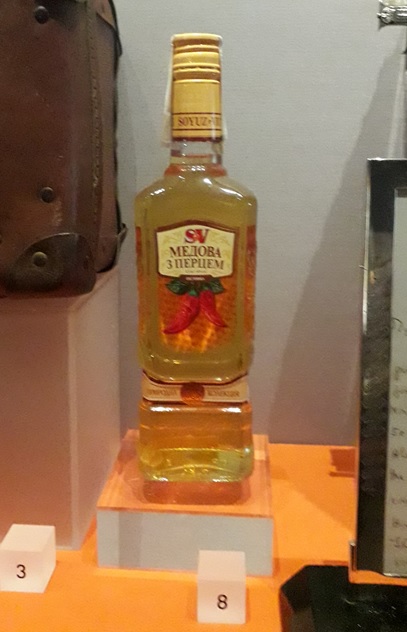

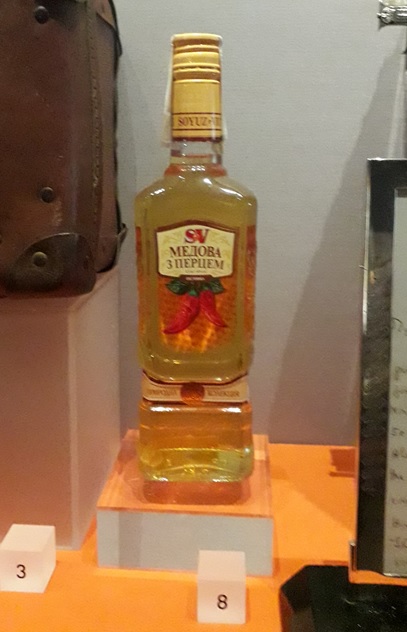

The reason for this particular theme being prominent in my mind is that April is the anniversary of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, and here in the Charge! Gallery at Discovery Museum, we have an unusual and poignant reminder of that momentous event. A bottle of vodka may not be the most obvious exhibit for a regimental gallery, but stay with me on this one.

15th/19th The King’s Royal Hussars landed on Gold Beach on 16 August 1944 eager to play their part in the liberation of Europe and believing their cause to be a just one. By spring 1945, this idealism had largely evaporated and had been replaced by a desperate day-to-day struggle for survival. Their progress through Northern Germany to the Baltic as part of 11th Armoured Division was dogged by fierce German resistance despite the increasing hopelessness of their situation.

A curious event occurred on 12 April as the Division approached the River Aller. The local German commander approached 11th Armoured Division under a white flag and sought a temporary ceasefire. He explained that a little further north was a camp containing thousands of political and criminal prisoners. He went on to say that there was an outbreak of typhus and if the prisoners were to break out there was danger of an epidemic. The officer said the camp was run by the SS and that the Wehrmacht (the German army) had known nothing about it. He offered the British commander safe passage across the Aller if the German forces were allowed to disengage and retreat north. As it transpired, the precise terms of this agreement could not be agreed upon, and in the subsequent action over the next couple of days the 15th/19th sustained a number of casualties.

Being oblivious to this incident, the regiment had no reason to expect that 15 April 1945 would be a day any different from those of the last few months; they made their preparations that morning, unaware of the scenes that they would see later that day, unimaginable scenes that would stay with them forever.

It became clear quite early that their recent routine of pushing forward through Northern Germany clearing up any enemy still fighting wasn’t happening that morning. The roads were unusually busy with traffic and pedestrians, some of the vehicles with white flags. And then there was the smell. The air seemed to have a peculiar smell, greasy, but more than that, which one couldn’t recognise. Eventually, the order came to move, with the added instructions that when they came to the camp they were not to open the camp gates, let anyone out, feed or touch anyone and, if that wasn’t enough to add to the men’s feelings of unease, leave the German guards on duty.

On approaching the camp, their apprehension increased; they could see the barbed wire, then the watch towers still manned by the German guards, and then the inmates. The soldiers stared speechless at the sight before them.

One of these soldiers was 21 year old Ian Forsyth. We are doubly fortunate in that not only is Ian still with us, but that he has committed his testimony to print. In this testimony, he does not actually describe the things that he saw that day in any great detail, and certainly I do not have adequate words to describe the horror. We have all seen the newsreels, and the words of Richard Dimbleby of the BBC are as appropriate as any I have heard:

‘…Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which… The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them … Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live … A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child, and thrust the tiny mite into his arms, then ran off, crying terribly. He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days.

This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.’

What Ian Forsyth does do, with remarkable candid and moving clarity, is talk of the effect this day has had on him and his comrades. Despite orders to the contrary, someone threw some army rations over the wire. How could a human being stand by and do nothing? Those at the back surged forward and trampled on those at the front to get to the food. Those who got the food would almost certainly die anyway, their bodies unable to handle the food. It took the medical authorities some days to establish how best to nourish and feed the liberated prisoners.

The 15th/19th Hussars never entered Belsen. They were front line fighting troops and needed to press on. It was left to others in the following days to enter the camp and discover and deal with the full horror of what had taken place there. There was no time to come to terms with or seek counselling for the horror they had witnessed. That wasn’t the way things were done then anyway. One thing that Ian does say is this experience reminded them of the reason they were fighting this war, and a little of the old idealism returned.

The day after the liberation, the regiment were back on operations and Ian and his troop had good cause to regret the failure of the proposed cease-fire. Whilst on reconnaissance in a wood, a job Ian hated, a German column was spotted and orders were given to allow it to pass. A short while later an 88mm shell hit them, destroying one of their tanks and seriously wounding the crew, including the troop leader and a young Jewish front gunner who had come over to Britain on the Kindertransport just before the outbreak of the war and enlisted as soon as he could. At that time, particularly near the end of the war, soldiers could never be sure if their wounded comrades survived or not, as the wounded were evacuated and the surviving troops pressed on.

Ian Forsyth has had to find a way to live with his demons since then. He has done this by facing them and by telling others about them. Without going into detail, he indicates that some of his comrades have been less successful in their struggles with the past. He spent years as a teacher and has recounted his experiences to young and old. He has been back to Belsen on a number of occasions, it draws him like a magnet. He has made friends with former inmates and kept in touch with those that are still alive and the families of those who have passed on.

Bottle of vodka given to Ian Forsyth

At a ceremony commemorating the 65th anniversary of the liberation he was given a bottle of vodka by a Ukranian woman who told him ‘I have waited sixty five years to meet a liberator and say thank you. You are the first I’ve met, so this is for you’. Ian was never able to open that bottle, indeed he never wants it to be opened. It should be kept as a reminder of why he and his comrades were there in the first place. We are incredibly proud to have it at Discovery Museum.

I spoke to Ian last week to ask him if I could use his story for this blog. In conversation I asked him if he wished fate had not singled him out to be present that day and, after a pause, he said simply ‘it’s haunted me ever since, and it still haunts me today’.

There is a profoundly ironic postscript to this story. Only months after the end of the war, the 15th/19th were in Palestine, fighting against Jewish militant groups who wanted to evict the British authorities from Palestine to allow unrestricted Jewish immigration. Ordinary soldiers have great difficulty in coming to terms with this kind of contradiction, which appears totally illogical to them.

It goes against the grain for an old soldier to disagree with a senior officer, at least in public, but with reference to the quote at the top of the page I would suggest that the good Admiral is wrong. There are many extraordinary people in the world. Ian Forsyth MBE is one of them.

My grateful thanks to Ian Forsyth for granting me permission to write this. Ian lives in Hamilton, near Glasgow, is 95 years old but sounds 25 years younger. His story and the bottle of vodka can be seen in ‘Charge! The Story of England’s Northern Cavalry’ at Discovery Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne.