Bird eggs from Saltwell Park Museum. Photo by Karolina Maciagowska.

“Museums are most attractive when they, so to speak, are emerging from the egg. Upon reaching maturity they tend to magnificence and an awe inspiring plenitude of knowledge which causes one to surrender one’s superiority complex along with one’s umbrella”.

So writes one Tyneside journalist on 31 May 1933 about the ‘Gateshead Municipal Museum’ that opened in Saltwell Park on 8 July later that year. Over the next 80 years it was to be known via a number of official and unofficial names; Gateshead Municipal Museum, Gateshead Local & Industrial Museum, Saltwell Towers Museum and Saltwell Park Museum. The story of the museum and that of its collection is a complex one and a narrative of its short existence (it closed in 1969) reveals a lot about how we view regional identity, heritage and also museums.

I’m in charge of producing (or curating) a permanent exhibition at the Shipley Art Gallery that will be dedicated to Saltwell Park Museum and its collection. It will open on 11 June. It’s been a complicated project so far and a lot of hard work because I’ve tried to use the collection in a different way, that I hope will challenge how we think about local history, art, objects and the world around us.

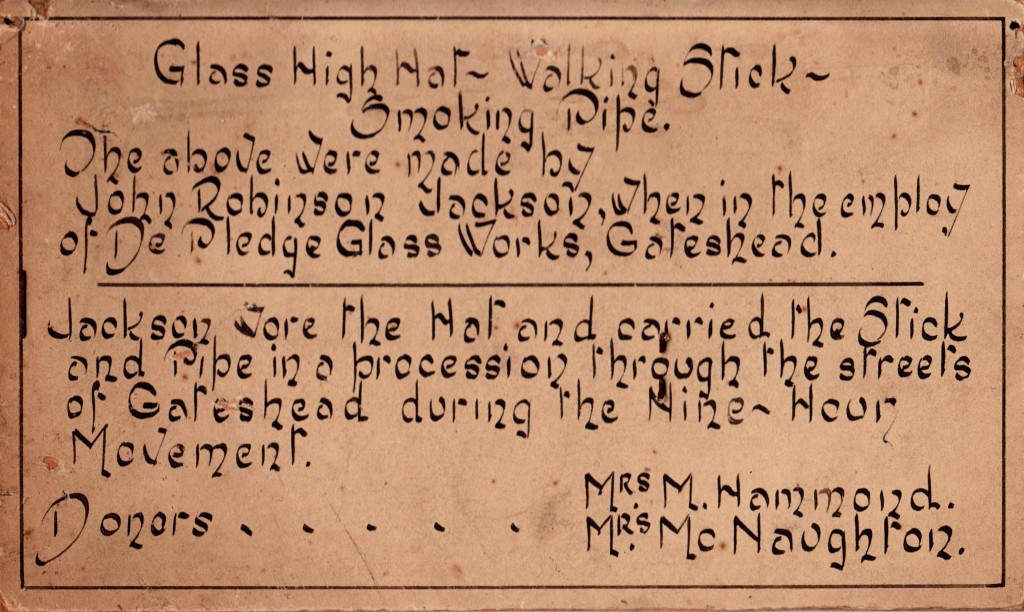

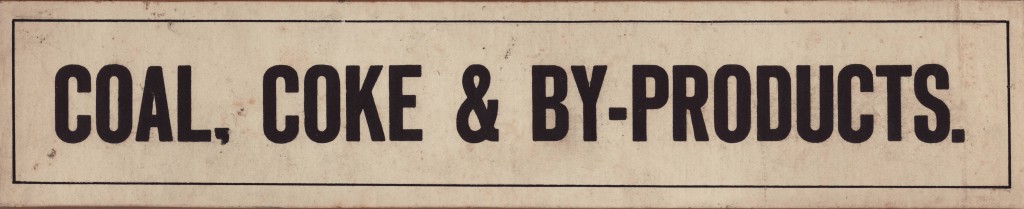

An original label from Saltwell Park Museum.

An added challenge when developing this project has been the fact that a lot of people in Gateshead, from a particular generation, feel very strongly about what happened to this museum and its collection. They have vivid memories of it and the objects that were displayed there. Its closure in 1969 and the perceived ‘loss’ of its collection has been a source of sadness and frustration.

Many of the objects from its collection have not been on display since it closed and this has led to the perception that they have been forgotten or discarded. The reality is a complex one. Saltwell Park Museum’s story and that of its collection is not straightforward. Museums, compared to the 1960s, are run differently. Collections management (the documentation, care and conservation of objects) is more efficient today. Saltwell Park Museum’s closure happened quickly and very suddenly and the collection that remained in the closed building could not be moved to safer storage for another five years, not until 1974, when Tyne & Wear Museums, the joint museum service was set up. The museum and its collection have, over the years, gained an almost mythical status in Gateshead.

Over three parts I’m going to try and tell a story about Saltwell Park Museum and how it connects to lots of different ideas about the world and the society we live in. I’m also going to shed some light on its collection and what happened to it.

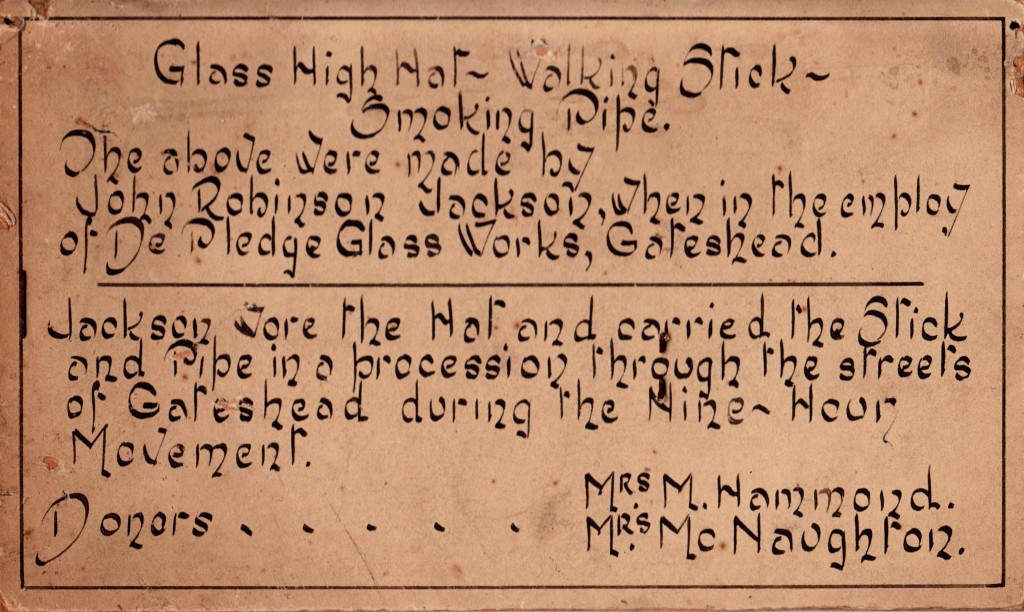

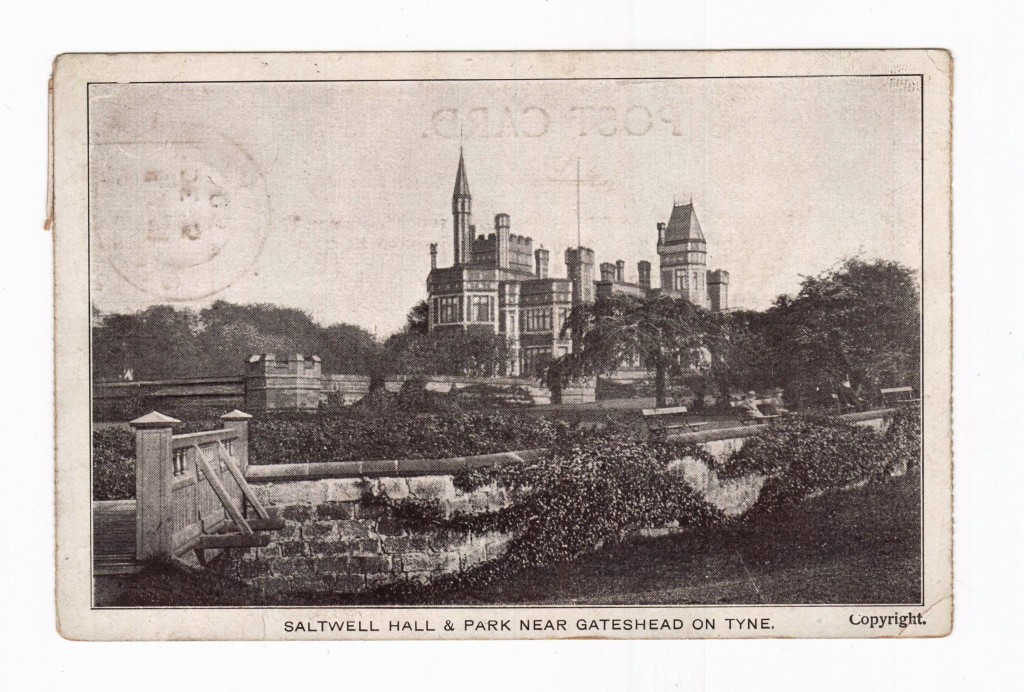

Postcard from 1902 of Saltwell Towers or Saltwell Hall as it was also called.

The museum was situated inside of Saltwell Towers, which still stands today. It was originally commissioned in 1856 by the Newcastle based stained glass manufacturer William Wailes. In order to tell a story about the history of Saltwell Park Museum itself we have to begin with another one: it’s about money, land, technological change, windows and imagined ideas about the past.

William Wailes owned the Saltwellside estate on which Saltwell Towers was built. He bought this land in 1850 and before moving into his new building lived at South Dene Towers, which was also on the estate. South Dene Towers was demolished and is now the site of Gateshead Crematorium on Saltwell Road.

William Wailes,who lived in Saltwell Towers and made lots of money from glass and windows. This painting is currently on display in Saltwell Towers, which is now a cafe and events space.

William Wailes made a lot of money from windows, at the time he was the proprietor of one of the largest and most prolific stained glass workshops in the North of England. One of his largest commissions was the windows of Gloucester Cathedral. In his twenties he had studied in Germany and later worked with Augustus Pugin. Pugin was very famous in Victorian Britain and is seen as a pioneer of something called the Gothic Revival style.

Gothic Revival was a style that sought to replicate a particular type of architecture popular in medieval Britain – the Gothic. Pugin and the Gothic Revivalists loved the medieval period. They thought that the buildings, architecture, materials and methods used during this time were the product of a purer society. Pugin in particular wanted to see a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages. They were inspired by romantic ideas of the past. They imagined what life was like in medieval Britain and they wanted to emulate it in order to create a better world.

Britain during the Victorian period was experiencing an industrial and technological revolution that would set the foundations for the modern world as we know it. In a strange way the romanticism of the Gothic Revivalists was a retreat from what was happening around them, things were changing very quickly and they didn’t like it. They thought they could create a world that was much simpler, where the divisions between God, nature and people were less complicated.

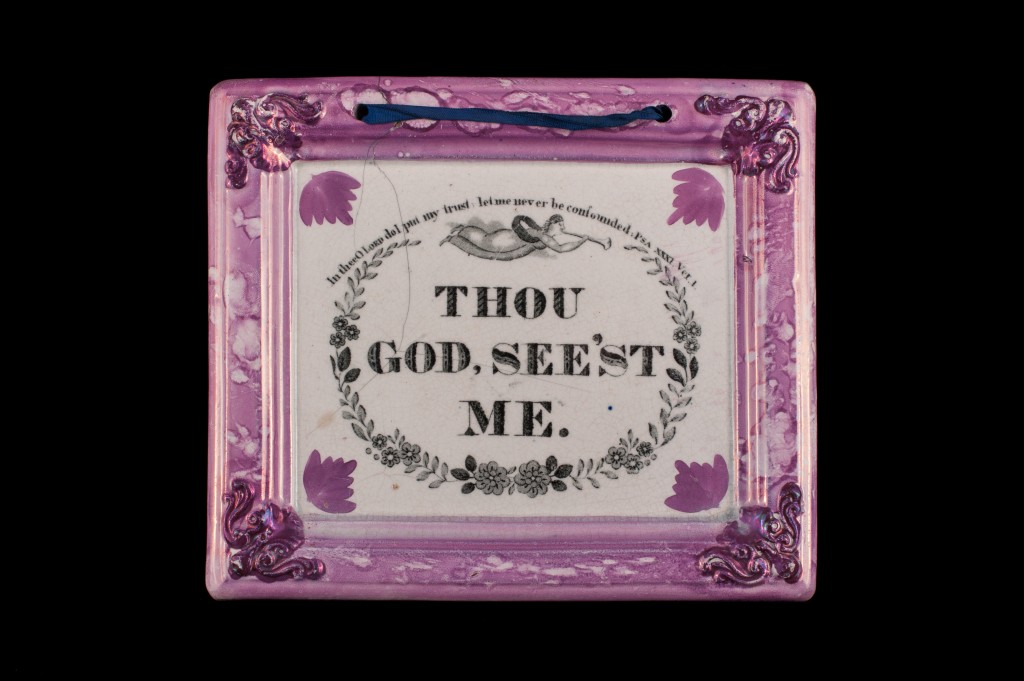

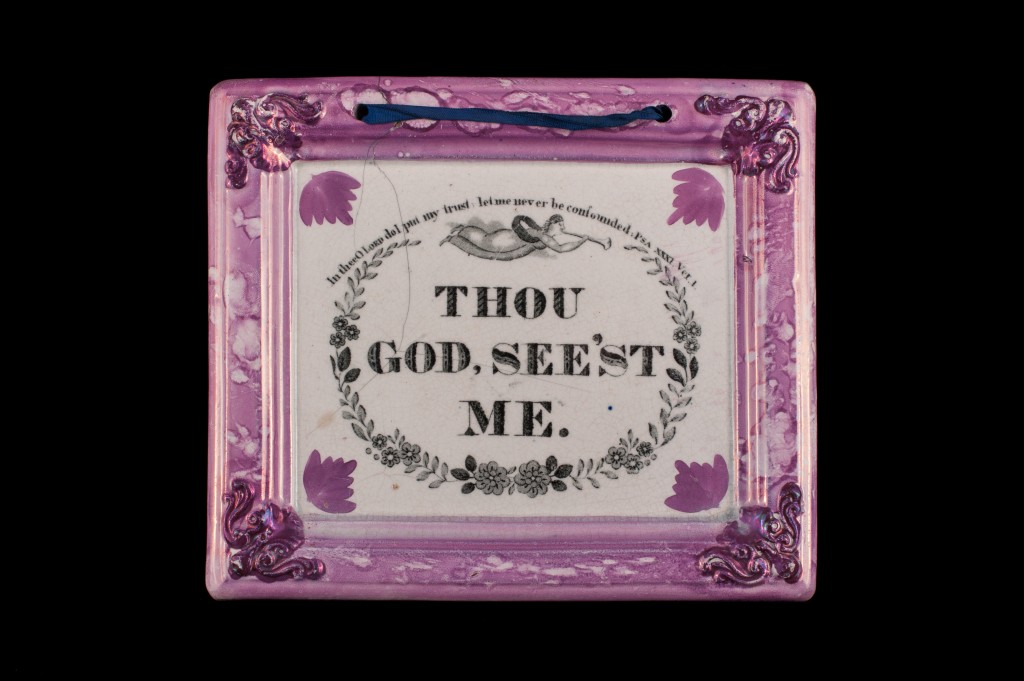

Object from Saltwell Park Museum Collection. Photo by Karolina Maciagowska.

In commissioning Saltwell Towers William Wailes built himself a retreat, a kind of dream-like fairy tale castle where he was the overseeing medieval lord of a large estate. It is interesting that today Saltwell Towers, as well as being a cafe, is marketed as an events space where you can have ‘a fairy tale’ wedding. Saltwell Towers isn’t what you would call a classic example of the Gothic Revival. It’s an unusual building with an odd mix of architectural styles.

William Wailes’s dream didn’t last long. He sold Saltwellside estate and Saltwell Towers to the Gateshead Corporation in 1875. The estate became Saltwell Park and opened in 1876. It was dubbed ‘The People’s Park’, designed by a man called Edward Kemp and became a public space owned and managed by the Gateshead Municipality. William Wailes carried on as a private tenant in the Towers up until his death in 1881.

A sublime landscape. This isn’t Saltwell Park. It’s a print of a painting by John Martin from 1857 called ‘The Plains of Heaven’ from the Shipley Art Gallery Collection.

Saltwell Park today is a very beautiful place, it remains true to its original concept and design and it is still, along with Saltwell Towers, in public ownership. If you enter from the North East gate on a bright summer’s day it feels as if you are in a different world. The trees, horticulture and the expanse of green that surrounds the large boating lake fill the panorama. It isn’t by chance that it feels palatial; it’s been designed that way. It could almost be described as sublime.

Before the 19th century capital and land ownership were concentrated via the inherited wealth of aristocratic families but by the mid 1800s the power and money had shifted to the new industrialists, merchants, bankers and solicitors of the industrial revolution. From this new wealth a benevolent middle class emerged who wanted to build things that everyone could share and enjoy, not just rich people. They wanted to create a better world, just like the Gothic Revivalists.

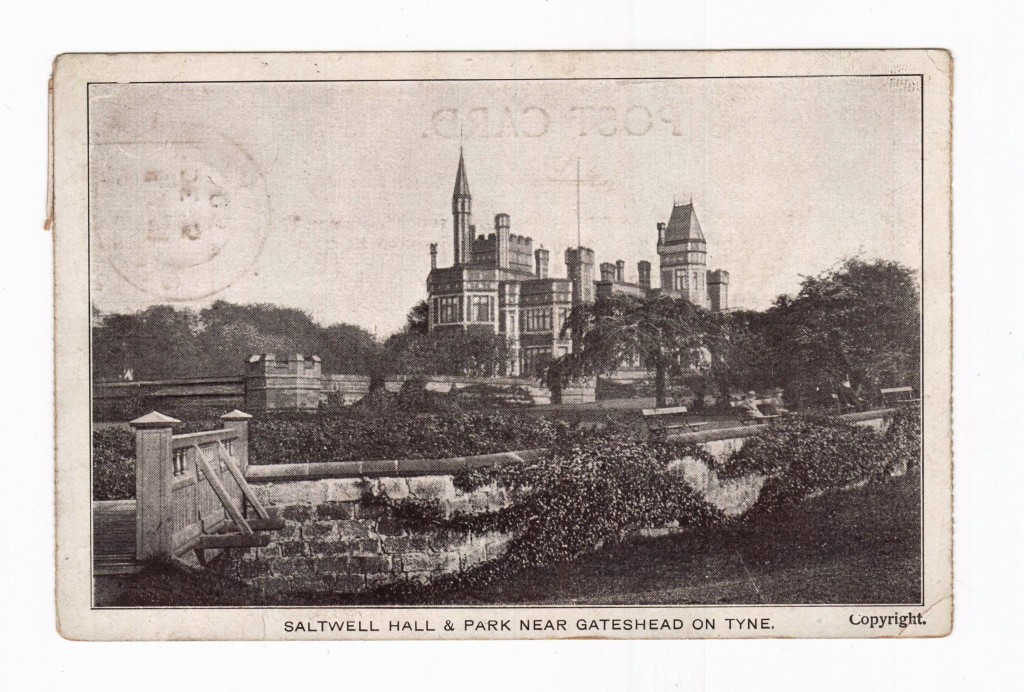

An original Saltwell Park Museum label.

At the peak of the North East’s industrialisation, of which Gateshead was a particular hub, Saltwell Park must have felt like a fantasy in green compared with the heavy industry and engineering not a mile back up the Great North Road by the River Tyne. In some respects it was a dream; it was the carefully managed and imagined idea of nature and society initiated by a benign and newly emerging middle class.

Saltwell Park’s design and use can be traced back to a number of things. The 19th century rise of Socialism and the social movements towards public ownership and the improvement of public health gave birth to campaign groups such as the Commons Preservation society, formed to protect public access to rights of way and open spaces, whose founders included people like William Morris. Municipalities and local boroughs grew in power via the acts of parliament like the Municipals Act of 1835 and various Public Health and Reform Acts.

A Redshank. Taxidermy from Saltwell Park Museum Collection. Photo by Karolina Maciagowska.

The new industries of the 19th century required workers and gradually urban centres, like Gateshead, quickly became densely populated due to the migration of people. As a result inequalities in wealth, life expectancy and living conditions grew. Extreme poverty linked with poor housing created widespread health and social problems for a large number of people.

Someone recently described to me the cultural rebirth that grew out of these conditions as a kind of benign ‘avuncular despotism’, led by municipalities and local councils. It was an idea concerned with ‘civic pride’, ‘public good’ and the ‘improvement’ of people through culture. The opening of Gateshead Local & Industrial Museum in 1933 is a legacy of this cultural shift as are the public parks, libraries, museums and art galleries that populate our cities and towns today.

Front cover of brochure from 1950s advertising Shipley Art Gallery and Saltwell Park Museum.

Read Part 2 of What ever happened to Saltwell Park Museum?