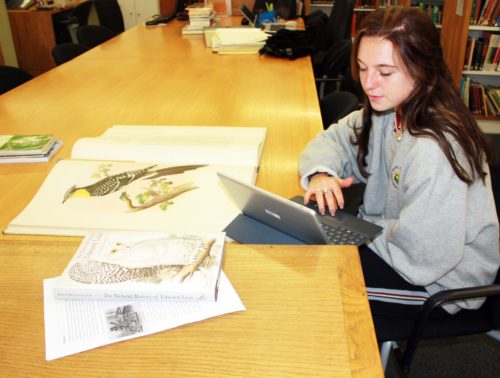

Immy Mobley with John Gould book

Lithography and the impact it had on zoological illustrations

Hello, my name is Immy and I am researching the use of art in natural history illustration during my placement at the Great North Museum: Hancock Library. The Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) has a wonderful collection of books about the natural world that is located in the library. Many of these have beautiful illustrations with examples dating back to the 16th century.

I have always been passionate about art and therefore was excited to start my project by gaining information on the history of illustrations, dating back to cave drawings from over 30,000 years ago to the many different methods used to produce illustrations in the most recent centuries, and how these changed over time. I found lithography particularly fascinating, due to the simplicity of the method, yet how much of an impact it had on the publishing of natural history books during that era. Subsequently, I looked into the process more closely.

I learned that lithography is a method of printing, based on the repulsion of oil and water – they do not mix. It was discovered by a German author and actor in 1796, named Alois Senefelder, who originally invented it as a cheap method of publishing theatrical material. However, it also resulted in the development of zoological art being greatly advanced during this period, although not immediately, with the first book about animals to use lithography by Karl Schmidt being published in 1818 (Beschreibung der Vogel). It could be said that the application of lithography to animal illustration was one of the most important aspects of nineteenth century zoological literature.

Alois Senefelder 1771 – 1834

Previously, an illustrator made a drawing and then handed it over to an expertly trained engraver, who would translate the original drawing into an engraving. The artist therefore had little to no control over what happened to his work after it left his hands. However, lithography meant that the artist could be his own lithographer. The artists now had the freedom to draw directly onto the stone making animal illustrations seem more vital, individual, and detailed than before, raising the importance of the quality of illustrations in zoological publications.

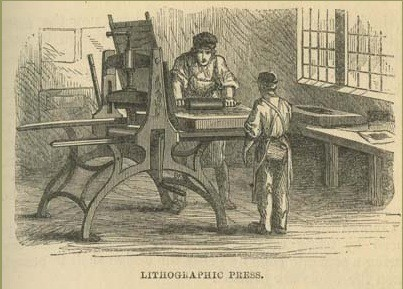

At this time, lithography involved an image being drawn onto a thick slab of limestone using a greasy crayon, which may have been pigmented to make the drawing visible. The stone was then treated with a mixture of weak acid and gum Arabic, creating a layer that would not accept the printing ink, but would retain water when the stone was dampened. This meant that when an oil-based ink was applied, it would only stick to the original drawing, so as the stone and a blank piece of paper was run through a press, the image was transferred, creating the print. In modern lithography, the image is made of a polymer coating applied to a flexible plastic or metal plate.

I think that a great example of an artist using lithography to succeed in zoological illustrations is John Gould, who was an English ornithologist in the nineteenth century. He used the printing method to portray birds of the world for most of his life and was directly responsible for the publication of over three thousand hand-coloured lithographs of birds, most of which were shown in life size. Gould was described as ‘the greatest figure in bird illustration’ and he frequently worked with Charles Darwin to identify numerous bird specimens. It is of common opinion that his most impressive illustrations were in the “Birds of Great Britain”, of which he produced solely 750 copies, being described as ‘the most sumptuous and costly of British bird books’. The NHSN library has a version of this title in 25 volumes. Like all of the books in the library, this is available for anyone to view. Personally, I was impressed by the accuracy and liveliness of the illustrations, with the finer details being complemented by the bold use of colour.

Gould later commissioned Edward Lear, who was another great lithographer, to produce images of birds for his publications. It has been argued that Lear was a better artist than Gould, which gives me reason to continue my research in the direction of Lear, and write my next post about him and his artwork, some of which I will also be able to see as part of the NHSN’s collection.

One Response to The Art of Nature Part 1 – A guest blog by Immy Mobley