School Ship on the Tyne – The Training Ship Wellesley at North Shields 1868 – 1914.

The driving force behind having a training ship on the Tyne was James Hall, a local shipowner. Hall was worried about declining numbers of British seamen aboard the nation’s merchant ships, but he was also a social reformer with concerns about the links between poverty and crime. He proposed that a ship be brought to the Tyne and an Industrial School be established aboard. The Industrial Schools Act of 1866 had given magistrates the power to send to a certified industrial school any destitute child under 14 years.

James Hall saw this as an opportunity both to help neglected boys and ensure a steady supply of British seamen to the merchant fleet.

The former 74 gun ship HMS Cornwall was acquired and brought to the Tyne. The ship was moored opposite Coble Dene, North Shields and on July 30th 1868 she was inaugurated as the training ship Wellesley.

In 1873 HMS Boscawen replaced the old Wellesley and took on the Wellesley name. She was still at the Coble Dene mooring when the nearby Albert Edward Dock opened in 1874, but soon after she was moved to a mooring off the North Shields Fish Quay. Most likely her presence moored close to the entrance of Albert Edward Dock was a hazard for ships entering or leaving the dock.

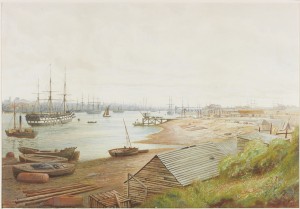

River scene c1880 with the second Wellesley moored off Coble Dene, North Shields in a watercolour by B B Hemy. TWCMS : G7299 South Shields Museum

View of the Tyne featuring Wellesley at her mooring off Coble Dene. Watercolour by T M Hemy 1881 TWCMS : G5014 Shipley Art Gallery

There was an expectation that many boys would go on to a life at sea, but Wellesley was primarily an Industrial School. Seamanship skills were taught, but schooling, and what we would call work experience, were given a higher priority.

Boys received an education that was comparable to that which they would have received in an ordinary school. There were examinations every year and boys received a grade just as they would have done ashore.

In 1906 Wellesley sent 69 boys to sea in British merchant ships and 2 boys to foreign vessels.

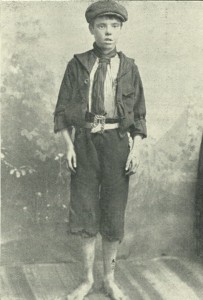

E J Hatfield – Wellesley boy 1912-1916

E J Hatfield was brought to Wellesley from a children’s home in Meriden, Worcestershire aged 12. He seems to have thrived on the ship and was trained as a tailor. He was on the Wellesley when she caught fire in March 1914. In 1916 he left the school and joined the oil tanker ss Massasoit as an ordinary seaman and signal boy. He was still in the Merchant Navy at the end of the First World War, by then an Able Seaman who was beginning to make a success of his life.

Wellesley boy EJ Hatfield’s first ship, the oil tanker ss Massasoit, which he joined in 1916. TWCMS : G8017G

A key figure in Hatfield’s life was the tailor master aboard the Wellesley, Mr Warnly. Hatfield was probably partly chosen to be a tailor boy because of his small stature, but his abilities with the needle soon made him a favourite of the tailor master. When Hatfield went to sea he kept in contact with Mr Warnly by letter. After a year of correspondence the tailor master and his wife invited Hatfield to come and stay with them when he was paid off from his ship. Hatfield continued to spend most of his time at sea but at last, aged 18, the boy from the children’s home had a family and a place he could call home.

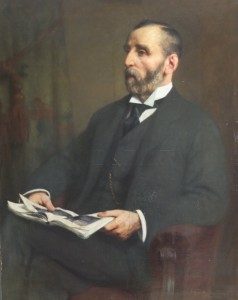

In 1977 the now Captain E J Hatfield was interviewed about his life aboard the Wellesley in a series of recordings lasting over three hours. These are now part of the audio collections of Discovery Museum. From the recordings we know that eventually he became a master mariner, and he was married, but apart from that we know almost nothing of his life between 1919 and 1977. Captain Hatfield’s memories of the Wellesley form the authentic ‘voice’ behind the exhibition. I found listening to the recordings fascinating, but also at times moving and sad.

“You were kitted out when you left the training ship for sea, given oilskins, but you weren’t given sea boots, so you can understand until I had (earned) enough money to buy sea boots, washing down decks and that in cold weather was pretty grim, especially (barefoot) on steel decks with the plate edges sticking up.”

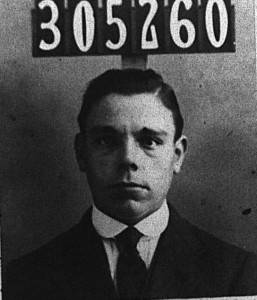

Captain E J Hatfield TWCMS : 2000.6119.2)

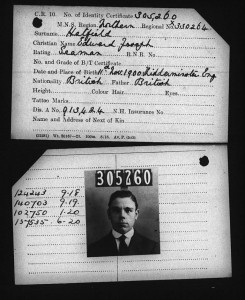

Online copies of Merchant Navy identity cards for Hatfield give us his first and middle names, Edward Joseph, and provided a black and white photograph of him taken in 1918. We also found out that he was 5 feet 5 inches tall (1.65m), had brown eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion.

Fire on the Wellesley

At 2.30 on the afternoon of 11th March 1914 a fire broke out in the Wellesley’s drying room. It quickly took hold and, despite the efforts of the boy firefighters and Tyne Commissioners fire tugs, the fire spread right through the ship. Hatfield was on board the ship at the time and he talked about what happened on one of the recordings.

Here’s an extract from the transcript of Hatfield’s interview to give a flavour of what it was like for the boys when the ship caught fire:

“So although the deck underneath was all alight, we didn’t know that. And the weight of water on top was making it a bit dangerous. They kept us there so long, and then we were told to go up on the main deck. There were tugs all around us. And I think when this order was given, it was decided to flood her and sink her. Scuttle her. I think that was their intention when that order was given, for us to abandon. I didn’t think that it was because of the dangers of the deck caving in. I think there was plenty of safety margin you see. But the fire had got such a hold that they couldn’t contain it and they were going to sink her. Well, we went up on deck. Of course, the atmosphere in the orlop deck, our eyes were watering because of the tar and pitch in the seams, you see? The smoke was colouring. Not the ordinary smoke, it was yellowy with this tar content in it. Therefore we had to go to the port every so often and take a breather and then come back. There was, there was no bother at all. We weren’t panic stricken. It was all orderly. It was just, had to be done sort of style. In fact I think most of us were glad that she was burning. And you’re not panicking when you’re happy, you know.”

E J Hatfield was among a group of boys operating a manual pump on the orlop deck. The pump was worked continuously until the order was given to abandon ship. As soon as the boys stepped back on one side others would take over. The boys carried on pumping even though they could see flames coming up from the bathroom below.

When the order was given to abandon ship the boys were mustered on the main deck and then they went over the side in an orderly fashion. Hatfield went into the tug Vigilant, but there were also other vessels taking boys and staff off Wellesley.

Soon after 6 pm the ship settled down on the bottom at her moorings, with a large part of her upper works and masts remaining above the surface of the river.

All the boys were taken on board the drill ship HMS Satellite where they stayed for the next two weeks. Satellite was cold in comparison to the centrally heated Wellesley and blankets given to the boys were infested with lice.

After the Fire

After the fire it was clear that Wellesley was a total loss and she was broken up. Satellite was not suitable as a school ship so a new home had to be found. The Wellesley boys were transferred to the Tynemouth Palace (known more recently as Tynemouth Plaza and demolished after a fire in 1996) where they stayed throughout the First World War.

After the war the need for a permanent home became urgent and the management committee was fortunate to secure the recently built submarine base at Blyth. The boys moved into the base on 18th May, 1920 and Blyth remained the home of the Wellesley for the next 86 years.

From the 1930s onwards Wellesley became more of a reform school but still took boys on a voluntary basis or who were destitute. In 1973 Wellesleybecame part of Sunderland’s Social Services Department. Gradually the nautical aspect of the school was reduced in favour of general education and training. Eventually Sunderland decided to close the operation and in 2006 Wellesley was shut down.

28 Responses to The Training Ship “Wellesley” at North Shields 1868-1914