Hello, my name is Brian Allen and I am privileged to be a volunteer in the special and unique Great North Museum: Hancock Library. Welcome to my second blog about some of the amazing books that can be found here. I am also a member of the Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) which has its Library and Archives located here. Some of the books are on the open shelves whilst the older and rarer texts are kept behind the scenes in a controlled environment. Any of the material can be requested and the librarian will make it available for you to view. NHSN books in the public area can be loaned by members of the Society, which has its office just along the corridor from the Library.

My first blog looked at the Collins’ New Naturalists series and referred to the “Old Naturalists” in passing. This was not an ageist comment about members of the Society! It was rather an acknowledgement that the Library has a valuable collection of books going back centuries demonstrating how natural history was observed and recorded in the past. I mentioned Gilbert White (1720 – 1793) whose “Natural History and Antiquities of Selbourne” (1789) is a classic.

Gilbert White

The Library has an early edition (1813) of this collection of letters to friends recording White’s observations of the natural environment where he lived in East Hampshire. As a parson-naturalist-ornithologist he enjoyed a privileged life style which afforded him considerable freedom to pursue his own interests. His aim was to “…induce any of his readers to pay a more ready attention to the wonders of the Creation, too frequently overlooked as common occurrences…”. If he did not succeed in fulfilling this aim he acknowledged the physical and mental benefits of his pursuits into old age not least through engaging intelligently with others. Today we have citizen science, social media and the opportunity to share our interests with others in classes, on field trips and when visiting nature reserves. This shared passion soon leads to friendly conversations with others doing the same thing.

Gilbert White is not the only significant old naturalist to have been a clergyman. Indeed there are several other clergymen represented in the Library’s collection who made very significant contributions both regionally and nationally. I want to look at a few of them in the rest of this blog.

My first Old Naturalist is a 16th century local man with the reputation of being the “Father of Botany”. William Turner (1509 – 1568) was from Morpeth where a garden now commemorates this remarkable polymath.

William Turner Garden, Morpeth

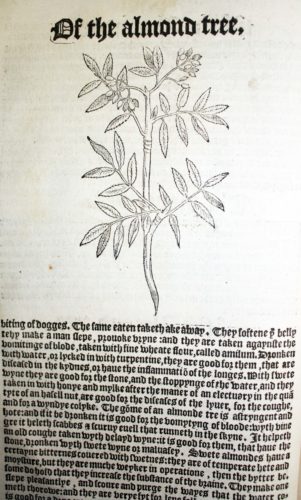

In those days clergy were often highly educated and from the type of backgrounds which made this possible. Turner, qualified in medicine and science, was no stranger to religious controversy as a Protestant Calvinist senior clergyman who became Dean of Wells Cathedral (1560 -1564). His major contribution to natural history is “A New Herball” first published in 1551. A rare first edition of this book is available in the NHSN library. I find it reassuring that he sometimes struggled in the task of identifying various plants. Despite the advances of science and popular publications it is still a tricky subject for me. Turner eschewed criticism and deliberately chose to write in English rather than in Latin, familiarly used in his day for academic and scientific writings. His argument was straightforward. He likened clergy who taught in Latin to warn their flocks of the perils of this life to a watchman on the walls of Berwick. On seeing the Scots approaching a warning shouted in Latin “Veniunt Scoti” would not be heeded and the Scots would take the town! “Were he not worthy to be hanged for this labour?” asks Turner. Turner followed the convention of using Latin when classifying plants and drew on ancient texts, nonetheless. His illustrations were from woodcuts by the German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs whose own book in Latin was first published in 1542. They may not always be a reliable guide to identification, but it is possible, apparently, to identify plants today from many of those pictured in the Herball.

A page from “A New Herball”

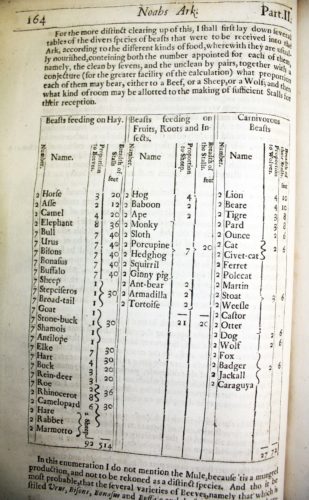

If you visited the Library when Dippy was in residence you might have seen a copy on display of John Wilkins (1614 – 1672) and John Ray’s (1627 – 1705) “An essay towards Real Character and a Philosophical Language”. This was published in 1668 and attempts a systematic approach to all that was known about the world at that time. This included a fascinatingly arcane example when applied to the Bible account of Noah’s Ark. The description of how all the animals would have fitted into the ark comes with lists and an illustration.

Noah’s Ark List of Animals

Wilkins was clearly regarded as an important intellectual clergyman of his day. He had the unusual distinction of having been head of colleges at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, became Bishop of Chester and was a founder of the Royal Society of which he was made a Fellow.

My next old naturalist is John Wallis (1714 -1793). He was a curate at Simonburn in the North Tyne valley for some years and published in two volumes “The Natural History and Antiquities of Northumberland…” in 1769 also in the NHSN library. The first volume describes minerals, fossils, plants and animals and the second volume follows three tours around the county. Both volumes are selective in their contents. For example, in choosing which birds to mention, he focuses on the “most curious and uncommon” including what he calls a “penguin” which today we know to be a (now extinct) great auk.

When walking in Wallis’ footsteps around Simonburn earlier this year, we followed a brown hare along a lane for a minute or so before it ran across the fields. Wallis includes the brown hare in Volume One. He wished “…our young sportsmen would have more regard to their preservation, and their own pleasure and not hunt them down annually like wolves and bears, to be extirpated without mercy…for the pitiful and brutal ambition only of the boasting among their companions of their killing…Savage and inhuman butchery! Away with it from Northumberland!..”.

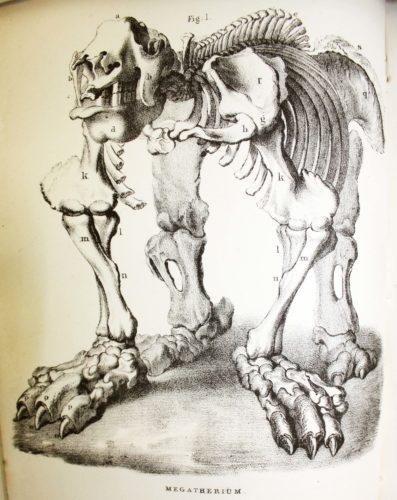

Another book displayed in the Library during Dippy’s stay was by William Buckland (1784 – 1856), the next old naturalist. He was a Reader in Geology and Mineralogy in the University of Oxford, a Canon of Christ Church, Oxford and later Dean of Westminster. His book “Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology” was published in 1836 and is in the NHSN Library. He did a lot of work on fossils and was the first English scientist to follow the glaciation theory of the Swiss-American biologist and geologist Louis Agassiz. Nonetheless he held the Biblical Flood to be the cause of all erosion and sedimentation as he sought to reconcile his findings with Biblical narratives. His work contains the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, now known as Megalosaurus.bucklandii, and is displayed in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. There are also fine illustrations of the skeleton of an extinct elephant sized sloth, endemic in South America, from the Early Pliocene to the end of the Pleistoscene.

Buckland Image

My final “parson-naturalist” is a son of the vicar at Eglingham, Northumberland, Henry Baker Tristram (1822–1906). Like his father he became ordained but travelled very widely, especially in the Near East, North Africa and Japan whilst Rector of Castle Eden in County Durham. He became a Canon of Durham Cathedral and a Fellow of the Royal Society. He found the theories about evolution expounded by Darwin and Wallace initially most persuasive. On considering a “series of about 100 larks of various species before me…” he claimed “…I cannot help feeling convinced of the views set forth by Messrs Darwin and Wallace” (Ibis 1859). He changed his mind later following a debate which took place in the Oxford University Natural History Museum. Tristram was a founder of the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) in 1858 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society. The BOU is one of the world’s oldest and most respected ornithological organisations with membership stretching across all continents and publishes “IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science” which is available in the NHSN Library. Being handy with a gun as many collectors of ornithological data were then, he gathered a large collection of bird skins which he later sold to a Museum in Liverpool. The Library holds a copy of Tristram’s book “The Natural History of the Bible, being a review of the physical, geography, geology and meteorology of the Holy Land, with a description of every animal and plant mentioned in Holy Scripture” (1867).

Some of the world views behind these writings may well seem remarkably at odds with contemporary science. However, these old books bear witness to several centuries of “parson-naturalists” taking very seriously the business of observing and recording their encounters with the natural world. They were not merely exercising a casual interest or practising what we might call today a hobby. They were intelligent, skilled and dedicated men whose legacy is to have contributed to the foundations of our understanding and exploration of natural history today. Women and men of all ages and from a wide range of backgrounds engage in the study of natural history today, whether as professionals or amateurs (that is, those who love the subject). Many more books have been written and will continue to be published to contribute to the growth of our understanding of nature. Some of them are to be found in the Great North Museum: Hancock Library which also houses special displays from time to time. Do come and explore these riches for yourself!

The Library is free to use and open to everyone. Further information can be found at https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives