I am so excited for our upcoming event, Time Kitchen (Wed. Feb 22nd) to nibble delicious historic dishes and learn more about ancient recipes!

This event has inspired me to look into the history of cookery books, and the recipes in our museum collections.

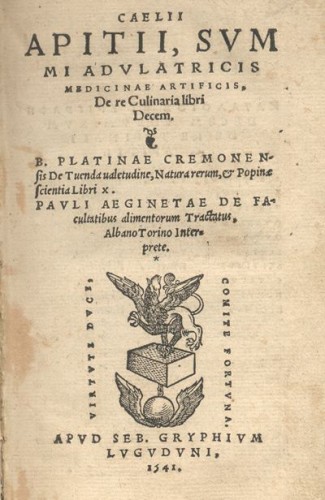

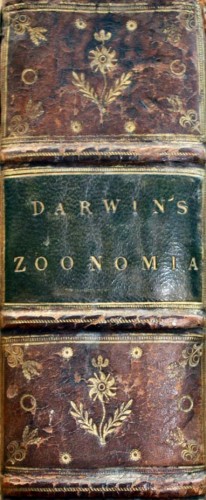

The earliest surviving collection of recipes in Europe is De re coquinaria (The art of cooking), potentially by Marcus Gavius Apicius, an early version of which was compiled in the 1st century. The version currently used is believed to have been compiled in the 4th or 5th century, and the first print edition was made in 1483.

(If you want to taste a dish right out of ancient Rome, drop by the Time Kitchen event on Feb 22nd, and try the Roman lentil casserole!)

Since Medieval times, competition among nobles to host the most lavish feasts encouraged the rise of professional cooks, and recipe compilations aimed at the cooks for grand houses. But the first recipe books for domestic readers were still to come. In the 19th century, the emerging Victorian middle-class desire for domestic respectability encouraged the emergence of cookery books in a form we would recognise today.

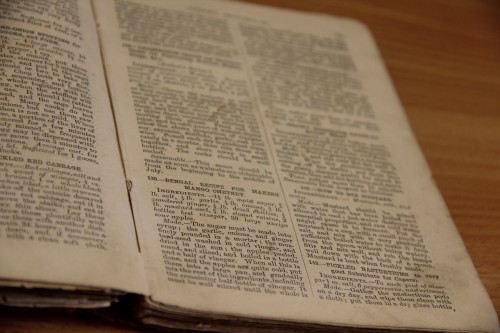

In 1845 Eliza Acton published the first cookery bookn for domestic audiences, Modern Cookery for Private Families. This book established some of the norms for writing about cookery that are still practiced today. For example, she divided the book by types of food and meals, listed the ingredients and amounts needed, and suggested cooking times for each recipe. She also included sections for foreign recipes, mostly for chutneys, although these may not have been widely enjoyed until after the second World War.

Eliza Acton’s book influenced possibly the most famous British cookery book writer of all time- Mrs Isabella Beeton.

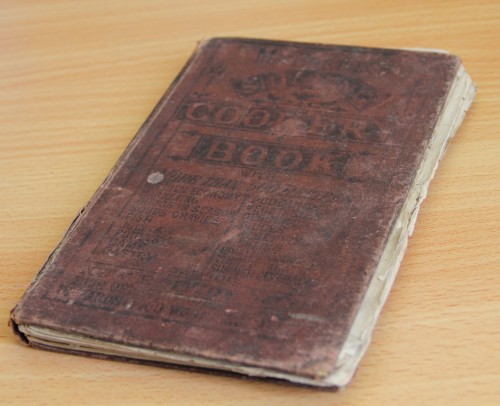

Her book, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, was published in 24 monthly instalments between 1857 and 1861. Mrs Beeton was more like an editor than writer, as many recipes were plagiarised from earlier writers, including Eliza Acton.

This book was mostly recipes, but also included advice on fashion, parenting, animal husbandry, household management, religion, and much else. Mrs Beeton’s book has been reissued in numerous editions and has never been out of print.

Although recipe books now are based, consciously or unconsciously, on Acton and Beeton’s Victorian cookery books, they have changed a great deal in the last century and a half.

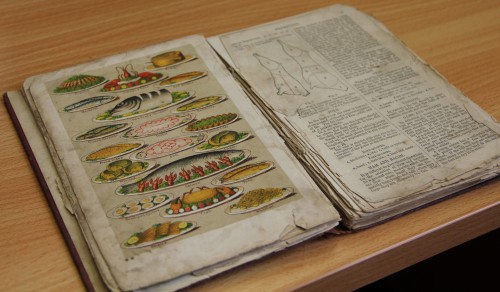

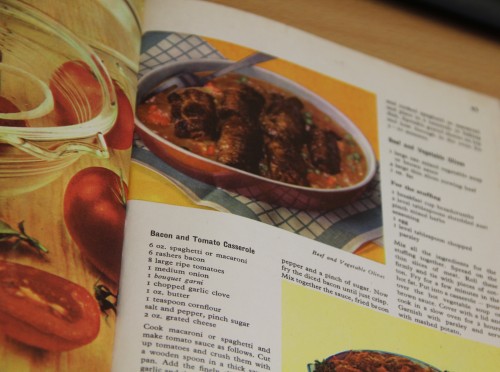

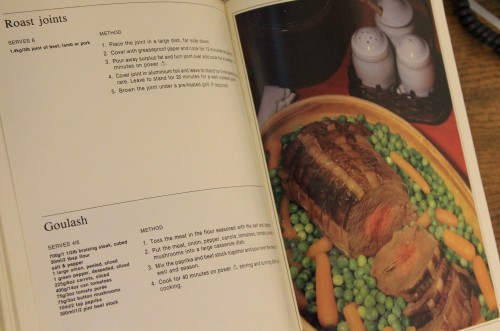

The way the recipes are written have changed to be more specific, to discuss adaptations for dietary requirements, and to incorporate colourful and tempting images to encourage domestic cooks (later editions of Mrs Beeton’s book began to include colourful illustrations as well).

The contents of recipes have also changed in line with what is in fashion, and what foodstuffs and technology is available to the domestic cook.

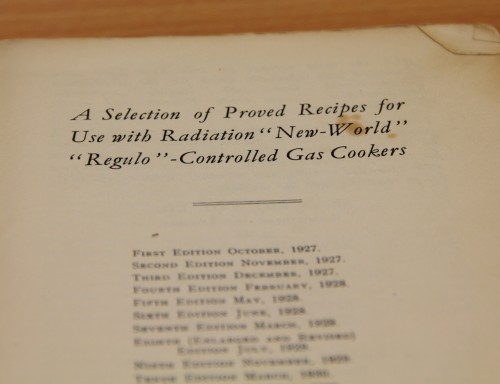

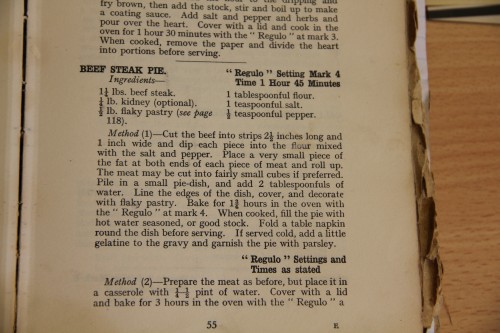

In the 1920s amd ’30s, gas cookers were a popular new technology becoming readily available to home cooks. Books of recipes adapted specially for gas cooking became popular.

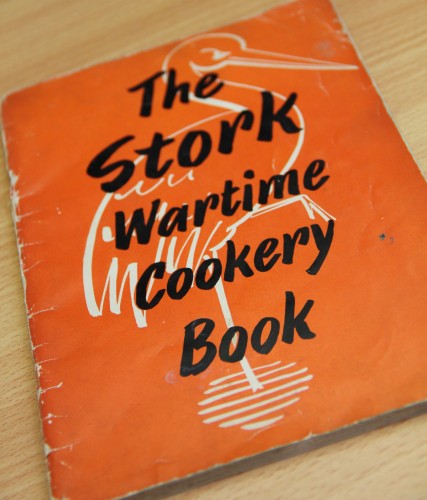

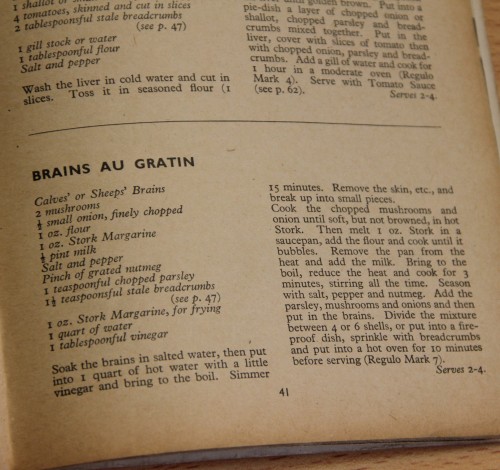

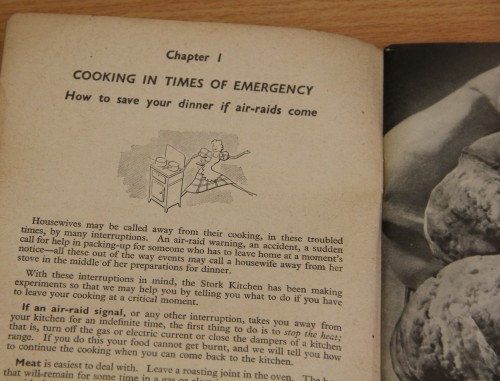

During World War II, rationing was instituted in 1939 and did not end until after the war in 1954. It limited what was available to eat, and resulted in some interesting recipes using every last bit of the cow!

This book also provides advice specific to wartime circumstances. You can imagine, an air raid siren blaring and thinking ‘Oh NO! My casserole!’

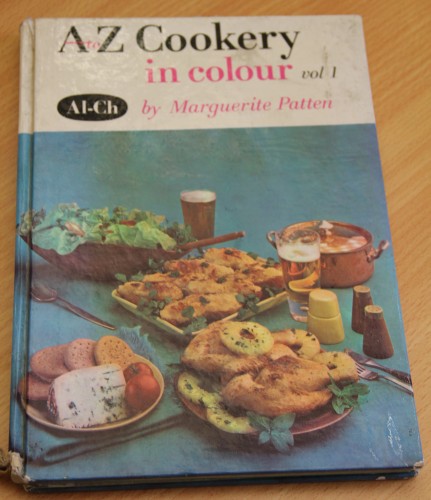

In the 1960’s the celebrity chef began to take off, and one of the biggest was Marguerite Patten.

Her encyclopedic books A to Z Cookery in colour provided recipes for anything the home cook would need to know, with beautiful images of the ingredients and finished product.

In the 1980s microwave cooking was suddenly available to the domestic cook, and it became all the rage!

Now cookery books come in thousands of varieties, ranging from books highlighting specific dietary requirements, to featuring specific ingredients, to celebrating indigenous foods around the world.

Yum!