Inspired by a collection of ‘Singing Sand’ samples in the Great North Museum: Hancock rock collection and accounts of earlier research, I’ve been given the opportunity to dig a little deeper and visit some local beaches where the sand has been reported to sing.

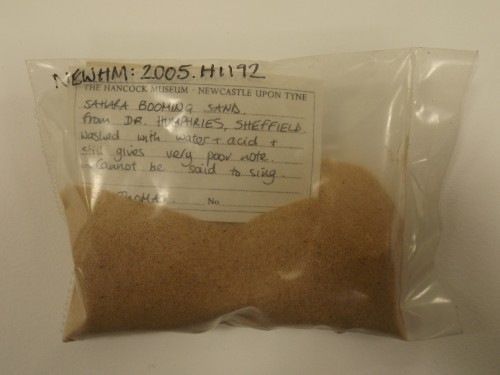

Much of what has been written on the subject of musical sands describes the sounds that occasionally emanate from sand dunes. An account of booming dunes in the Great Desert of Arabia published in 1947 describes them as having: ‘a deep musical booming sound’, which was often triggered by a group or individual walking across the dunes.

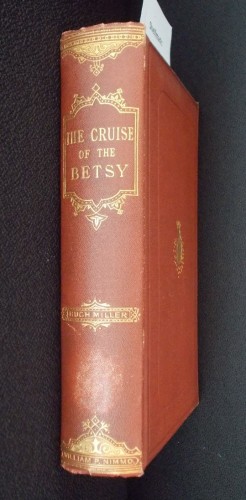

In contrast, the singing of beach sands has been likened to whistling or squeaking. The singing sands at Camas Sgiotaig near Cleadale on Eigg are well-known. Hugh Miller (stonemason, geologist, author and editor), is credited with their discovery during a visit in 1844. Miller observed that when striking the sand obliquely with his foot, the resulting sound was ‘a shrill, sonorous note’. A full account of his visit to Eigg is recorded in The Cruise of the Betsey, published posthumously in 1858.

In 1887 during the first lecture of the season ‘Grains of Sand’ to the Bournemouth Society for Natural Science, Cecil Carus-Wilson described the discovery of ‘musical’ sand on the beach at a spot between Studland Bay and Poole Harbour in Dorset, which ‘gives out a distinct note when walked upon or agitated by the hand or a stick.’ In his November 1888 lecture, he stated ‘This sample here is musical sand from Studland Bay. You will doubtless be disappointed to find that our local sounding sand cannot compete with the Eigg sand in point of musical attainments.’ At that time he was not aware of other singing sand deposits in Europe, but received a number of notifications regarding occurrences of musical sands (for example, at Arneil Bay in Ayrshire), following the publication of a letter in Nature (1888), entitled ‘Sonorous Sand in Dorsetshire’.

Closer to home Dr. J. Carrick Murray (in Tomlinson’s Guide to Northumberland 1888) writes:

‘Singing sands are to be found at Whitley, on the way to St. Mary’s Island. This sound is not musical, but rather a harsh whirring, or as Miller, in his Cruise of the Betsy, calls it, a ‘woo, woo, woo’. It is most marked when walking over, or rather through, the high dry oolitic sand beyond the slipping stones at the Briar Dene, just below where the volunteers encamp’.

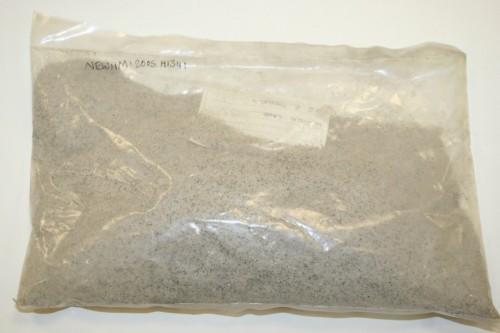

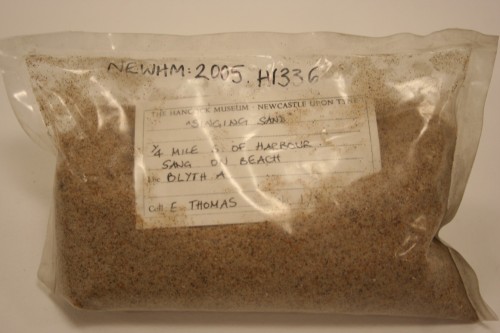

Local research during the 1960s pinpointed several sites along the Northumberland coast where the sand has been reported to sing, including locations near Seaton Sluice and Blyth where it was observed that the sand ‘sang on the beach’. This project involved the acquisition of more than 150 sand samples, both local and worldwide, which are housed in the Natural History Society of Northumbria petrology collection.

In 1973, Ridgeway and Scotton found ‘whistling sand’ at 33 places in Britain, including Bamburgh and Cullercoats in Northumberland, as a result of personal investigation and letters received. They were reasonably confident that their list was complete, having taken the trouble to investigate beaches adjacent to any that they knew to ‘whistle’.

The next stage of the project involves visiting local beaches where the sand has previously been found to sing. Working with Tim Shaw of Newcastle University who has the expertise to record the sound of the singing sands, this will be an interesting opportunity to explore the possibility of experiencing this curious phenomenon.

To be continued…

Thank you to John Cresswell of Bournemouth Natural Science Society for information pertaining to the singing sand research of Cecil Carus-Wilson.

Selected References

- Cruise of the Betsey. H. Miller 1858

- “Musical sand” C. Carus-Wilson. Bournemouth Soc. Nat. Sci. 2 (1888): 1-20.

- Comprehensive Guide to Northumberland. W.W. Tomlinson 1888.

- Mystery of Singing Sands. E.R. Yarham. Natural History Magazine 1947.

- MUSICAL SAND Part 1 The Singing Sands of the Seashore. A.E. Brown, W.A. Campbell, D.A. Robson and E.R. Thomas. Proceedings of the University of Durham Philosophical Society. 1961.

- Whistling Sand Beaches in the British Isles. K. Ridgeway and J.B. Scotton. Nature Vol. 238 1972.