A new gallery, Charge! The Story of England’s Northern Cavalry, opened at Discovery Museum on 21 October 2017. The Gallery gathers together the collections of the antecedent regiments of The Light Dragoons and also tells the continuing story of the Northumberland Hussars since becoming the Command & Support Squadron of the Queen’s Own Yeomanry.

The quality and historical importance of the objects on display are obvious. What is interesting is the personal stories of the men behind these objects. Over the coming months, I’d like to tell the stories of some of my favourite objects from the collection.

One of the stand out objects in the gallery is Chamberlayne’s shako, which was worn at the Charge of the Light Brigade. This engagement, which included the 13th Light Dragoons, one of the antecedent regiments of today’s Light Dragoons, is one of the British Army’s most iconic actions.

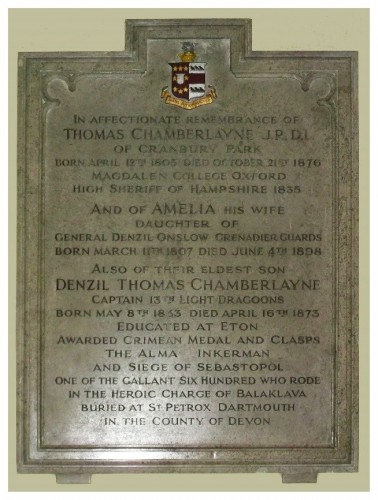

Denzil Thomas Chamberlayne was born on 8 May 1833 to a Hampshire J.P. and his wife, the daughter of a senior officer in the Grenadier Guards. His father, Thomas Chamberlayne, raced his yacht ‘Arrow’ in the inaugural America’s Cup race of 1851. Young Denzil was raised on the Cranbury Park estate south of Winchester, still the home of the family today, and educated at Eton. Being the eldest son, Denzil was expected to take over the estate from his father when the time came. The problem for privileged young men at this time was what to do with themselves until they came into their inheritance. Many of them opted for military service and in March 1853, a few weeks before his 20th birthday Denzil joined the 13th Light Dragoons, stationed in Hounslow, as a Cornet (2nd Lieutenant).

Fourteen months later, on his 21st birthday, Cornet Chamberlayne embarked for the Crimea. The campaign against Russia started badly and deteriorated, cholera struck our allies the French first in mid-July and reached the British troops only days later. By autumn it had decimated the ranks. That’s why, on 25 October, the Light Brigade could muster only around 670 men, barely the strength of a fully-manned regiment.

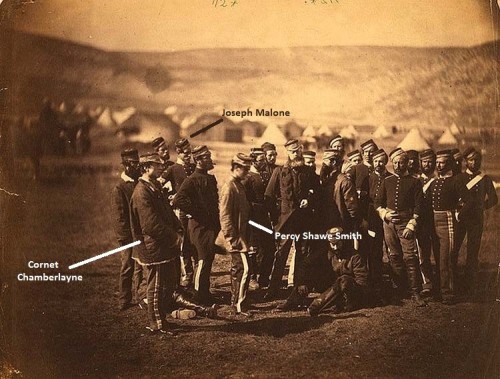

There are as many stories surrounding the famous charge as there are men who took part, and the details of petty jealousies between Commanders and misunderstood orders are very well documented. Cornet Chamberlayne, in a letter to his father dated two days after the battle, wrote of ‘very many hairbreadth escapes’ and describes how, being one of the last to make his escape back along the valley, his favourite horse ‘Pimento’ was just able to carry him out of range of the enemy guns before succumbing to two gunshot wounds.

Lieutenant Percy Shawe Smith of the 13th tells a tale of how, on returning down the valley he chanced upon Cornet Chamberlayne sitting beside his dead horse. The younger man asked what he should do. The advice given was to take his saddle and bridle and make his way back as best he could as “another horse you can get, but you will not get a saddle or bridle so easily”. This he proceeded to do and, displaying remarkable composure, he placed his saddle on his head and picked his way through the carnage of the battlefield back to the British lines avoiding the Cossacks who presumably took him for one of their own helping himself to a saddle.

There are details of Denzil Chamberlayne’s life after the Charge of the Light Brigade but sadly, not the circumstances or factors behind these details. He returned to Britain on 10 July 1855 on a ‘medical certificate’ but we can only speculate as to why this was issued; perhaps there are clues in the years to come. In March 1856 he was notified by Horse Guards that he was “to remain in this country”. At this time, the 13th were still in Turkey but were soon to leave and take up their post in Ballincollig, near Cork in Ireland. Was this evidence that he was still unfit for service?

In January 1862 he was commissioned into the Hampshire Yeomanry as a Lieutenant. He married his cousin Frances on 10 June 1867 and the couple set up home in Dartmouth. They had two daughters, one of whom died in infancy. Denzil’s father was still alive so it is possible that he was still searching for something to occupy his time until he inherited the estate.

Sadly, any thoughts that this was a model Victorian family, or that Denzil would inherit the family estate would be wrong. The Western Morning News of 6 February 1873 reported that Frances had been granted a judicial separation on the grounds of her husband’s adultery and cruelty. Evidence given at the hearing stated that he was often drunk, had ‘delirium tremens’ (usually attributed to alcohol withdrawal symptoms) four times and was violent and threatening towards her.

Denzil died on 16 April 1873 after what his obituary described as “a protracted and painful illness”. Clearly his life, at least in the later years, had been very unhappy. It may be speculation to attribute this to mental issues relating to his experiences in the Crimea, but the description of his home life in the previous paragraph would surely strike a chord with those people working with traumatised veterans today. These days, thankfully, we are aware of the mental toll that warfare can take on our soldiers, but in those days there was little or no understanding, and certainly no treatment, of the problem. Denzil’s tragic story is not unique amongst those who rode in the charge. Many of their number suffered problems in later life, as indeed soldiers have throughout history. The Spartans described the symptoms of PTSD in the period before the Roman Empire, which might be the earliest reference to the psychological condition.

The picture above shows Denzil Chamberlayne in a relaxed, if rather staged photograph of a group of 13th Hussars taken by the famous war photographer Roger Fenton. Also in the photo are Percy Shawe Smith and Joseph Malone, later to be awarded the VC for his actions at Balaclava.

A family memorial tablet in St Matthew’s Church, Otterbourne contains the following tribute to Denzil “One of the Gallant Six Hundred who rode in the Heroic Charge of Balaklava, Buried at St Petrox Dartmouth in the County of Devon”.

Chamberlayne’s shako can be seen in the Charge! The Story of England’s Northern Cavalry gallery at Discovery Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne.