Not to help the dancers find their way! Over the past year I’ve been working with the Sunderland ship model and ship portrait collections. In that time I’ve become unnaturally interested in a feature of some Sunderland-built ships from the 1880s and 1890s – a compass on the top of a 15 foot pole.

For hundreds of years seafarers using wooden ships used magnetic compasses to help them navigate. Once ships began to be made of iron, the magnetic field of a ship’s structure caused the compass needle to deviate. To prevent disaster something had to be done to counteract the effect of the hull. Adjustable iron balls were placed either side of the compass to reduce the influence of the iron hull.

Before she proceeded to sea, a ship would be ‘swung’ through all the points of the compass. The deviation of the compass was recorded and used to create a chart. This provided the helmsman with the precise adjustment needed for each heading.

The strangest modification, seemingly only in use for a short period in the 1880s and 1890s, was the pole compass, or in German Pfahlkompass.

As one might expect it was a compass mounted at the top of a pole situated on the bridge or some other piece of deck as far from the hull as possible. The pole compass appears in marine dictionaries of 1885 and 1890 but had disappeared by 1900. To read the compass somebody had to climb up the ladder that ran to the top of the pole. I can imagine it was not a popular task if the sea was rough!

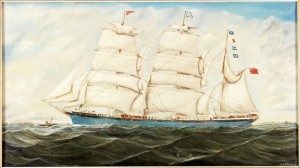

Detail of the painting of the barque Lota 1892 showing the pole compass just forward of the mizzen mast, out of the way of the sails and rigging

I don’t know why pole compasses had such a short life, but I find myself looking for them on every model and ship painting that crosses my path. The new Public Catalogue Foundation website: www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/ could easily become a guilty pleasure but one I’ve resisted up to now.

Anybody out there seen examples of pole compasses from before 1884 or after 1892?

24 Responses to Why put a compass up a pole?