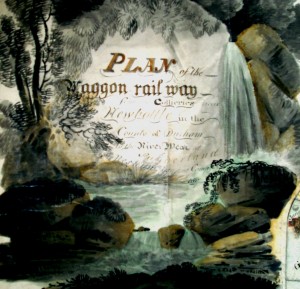

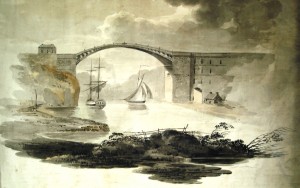

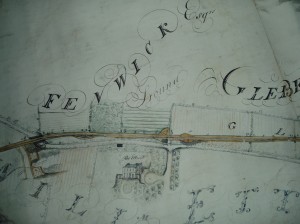

In August 2000 the museum was given a map of the ‘Newbottle Waggon Rail Way’ . This wagonway was built to transport coal in horse drawn wagons from John Newsham’s Newbottle Colliery to coal staiths on the River Wear at Galley’s Gill. The map itself dates to 1817, being drawn just 5 years after the wagonway was built. The wagonway is shown twice, as a true representation of the route and in a linear form showing distances between given points along the route. Also shown are the landowners of the properties over which the wagonway was built. It is also decorated with two drawings of horse drawn wagons and wagonway drivers and a view of the Wearmouth Bridge, one of the technological wonders of the age.

For most, if not all, of its existence the map has been stored rolled up. At about 7 feet long the map has been difficult to handle and until recently needed a long flat surface on which to show it. In 2011 the opportunity arose to have the map conserved. It was flattened, cleaned and framed by Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums and has been hung on a wall of the archive store for easy viewing. Plans are being drawn up to display the map in 2014.

Why all the fuss? The map is an important documentary source for the early history of railways and coal mining in the Durham Coalfield. In order to find out the story of the Newbottle Wagonway I went to Neil Sinclair who was the Curator of Sunderland Museum when the map came into the collection and who is a railway historian. Below is what he kindly shared with me. Neil adds that much of the information came from Colin E Mountford whose The Private Railways of County Durham is the standard reference work on the major colliery wagonways and railways of the area.

The Nesham family acquired the lease for mining at Philadelphia in 1734, initially in partnership with John Hylton. The title Newbottle Colliery (Newbottle was the nearest existing village) was used for a number of pits. One of these was the Success pit which first drew coal in 1750 and which was served by a wagonway running to staiths on the Wear at Penshaw.

In 1811 John Douthwaite Nesham began a policy of major investment in his colliery interests which included sinking the Dorothea Pit at Philadelphia, close to the existing Margaret Pit. A further development was the opening in 1812 of the 5.75 mile Newbottle Wagonway to transport the increasing amount of coal from his collieries to staiths in Sunderland.

At Penshaw and the many other staiths in the area coal was shovelled into keels (coal-carrying barges) and taken to Sunderland where it was transferred into sea-going collier ships for transport to ports on the East Coast of Britain. By building the line directly to Sunderland not only was the additional cost of transport by keel avoided, but unnecessary breakage of coal was also prevented.

The importance of this line was clear to the keelmen who saw their livelihood disappearing. On 20 March 1815 a group of keelmen and casters pulled down the bridge carrying the railway across Galley’s Gill in Sunderland and set fire to the staiths and the stationary engine house. The cavalry were called from Newcastle to quell the riot and the damage, which cost over £6000, was repaired.

The line to Sunderland put Nesham ahead of the other colliery owners on the Wear. In 1822 when his trustees were selling his property reference was made to ‘an easy Lead on a Iron Rail-Way to extensive Staiths at the Port of Sunderland, where the Coal is shipped by Spouts – an Advantage enjoyed by no other Colliery on the River Wear’.

The Wagonway was built on the ‘wayleave’ system, paying landowners for crossing their property. The sale document of 1822 details the wayleave rental including the Rector of Bishopwearmouth, Dr Gray, whose land was crossed twice including the area where the Royal Hospital now stands.

The Newbottle Wagonway was initially worked by horses with additional horses to help the trains of chaldron wagons up the steeper banks. The line terminated with a self-acting incline down Galley’s Gill to the staiths; loaded wagons pulled the empty wagons uphill. There were only a handful of railway locomotives in the country when the Newbottle line was opened. Nevertheless in 1814-1815 John Nesham tried out a locomotive built by William Brunton in Derbyshire which was essentially a steam boiler with a pair of jointed legs that ‘walked’ along the track (Details of William Brunton’s locomotive for the Newbottle Wagonway. (Andy Guy ‘North Eastern Locomotive Pioneers 1805-1827’ in Early Railways). It replaced horses between Margaret Pit and West Herrington. In 1815 the locomotive exploded near Philadelphia, killing about a dozen people, with many more injured.

After the 1815 explosion Nesham turned his thoughts to introducing more tried and tested technology – further self-acting and stationary steam engines which pulled wagons along the track through large drums of rope. In 1818 George Hill of Gateshead prepared a report (Northumberland Records Office 3410/East/1/141) proposing the installation of rope haulage on further sections. By 1822 there were three stationary engines (West Herrington, Middle Herrington and Arch) and four self-acting inclines (Grindon, Ettrick, Barras and Staiths).

A document dated 22 April 1822 (Northumberland Records Office 3410/Wat/59) gives the following details of the line:

Pit to bottom of bank, needing 5 men and boys and 5 horses

West Herrington Engine, 30hp, 12 wagons at a time

Flat, needing 3 men and boys and 3 horses

Middle Herrington Engine, 16hp, 8 wagons at a time

Flat, needing 2 men and boys and 2 horses

Grindon Incline

Arch Engine ‘near Mr Ettrick’s’ (High Barnes House), 16hp, 8 wagons at a time

Ettrick’s Incline

Barras Incline

Staiths Incline

In all the line needed 4 brakesmen, 5 staithmen, 22 men and boys with 15 horses constantly at work and 2 spare.

In 1822, John Nesham was in financial difficulties and his pits and wagonway were sold by auction to John George Lambton, soon to be the 1st Earl of Durham. Lambton linked the Newbottle line to his existing lines which ran from his collieries in the Fencehouses area and thus brought additional traffic over the Newbottle route and created the Lambton Railway. Contemporary sources suggest that the gauge of the Newbottle line was 4ft 0in and the original wagonways of Lambton, 4ft 2in/4ft 3in, so the Newbottle line would have had to be regauged to the Lambton track dimensions. Then in 1840 it was proposed to alter the Lambton Railway to the standard gauge of 4ft 8.5

inches and the conversion was carried out some time during the next few years.

A new colliery was opened at Houghton in 1823 and was linked to the Newbottle route. The need to increase the capacity of the line to carry traffic from Houghton and from the original Lambton collieries was probably the main factor in the Earl of Durham deciding to abandon more than two-thirds of the original Lambton route and to radically rebuild the remainder. The new route diverged significantly from the original line south of where it crossed Chester Road near the Arch Engine. Another factor may have been the wish to avoid the expensive wayleave charges he was paying for the original route. One surprising fact is that the new route meant abandoning a stationary engine which had recently been installed to replace the Grindon self-acting incline.

It is probable that the new route was built in the early 1830s as five stationary engines were ordered for it from R & W Hawthorn of Newcastle in 1830-1831, three at 56hp, one at 64hp and one at 80hp. It had certainly been completed by 1835 when John Buddle, the leading North East mining engineer, produced a very comprehensive report on the Earl of Durham’s collieries and railways and their working expenses (Northumberland Records Office 3410/Bud/28).

Buddle’s report of 1835 shows that the line was now largely worked by stationary engines (five on the Philadelphia – Sunderland section) and self-acting inclines at Grindon and to the Staiths. Buddle recorded that 49,141 chaldrons had been shipped in the half year ending 30 June 1835, probably totalling 132,230 tons.

In 1852 the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway (from 1854 amalgamated into the North Eastern Railway) opened its line from Pensher to Hendon, where it joined existing lines serving the new South Dock. The Earl of Durham’s Agent negotiated an arrangement for the Earl’s locomotives to haul his chaldron wagons over the new line to Millfield where a new link was built to the head of the existing incline to the Lambton Staiths in Hylton Road. This link was in use by 1855.

A detail from a print of Hartleys Glass Works, Sunderland by M and W Lambert showing the Glebe Engine House near the new Union Workhouse between Chester Road and Hylton Road (now the site of the Sunderland Royal Hospital), about 1855

A further new link was opened in December 1865 from the Pensher branch at Pallion via Deptford and a tunnel to the Lambton Staiths. This meant that Lambton Railway locomotives could take the chaldron wagons direct for shipment and obviated the need for the wagons to be uncoupled and then let down to the Staiths by the self acting incline.

After the completion of the Deptford link the traffic over the original Newbottle route probably ceased in 1866 when the last of several new tender locomotive to work over the Pensher line was delivered. The previously quoted date of 1870 must be wrong as the area, which included the Glebe Engine, was purchased by the Sunderland Union Workhouse in 1867 and almost immediately built over.

A new colliery at New Herrington was built over the course of the line about 1874. The stub of the route between Herrington and Philadelphia remained to serve the new colliery. Ironically Nesham’s original wagonway to the Low Lambton Staiths at Pensher remained in use until the 1890s.

The route of the Newbottle Wagonway in Sunderland between Hylton Road and where it crossed Chester Road disappeared fairly rapidly as housing in the Millfield area was built and the Sunderland Union Workhouse and Bishopwearmouth Cemetery expanded. South of Chester Road the route remained largely intact until it too disappeared under the vast house building programme of the 1950s and the landscaping of Barnes Extension Park. After the demolition of the bridge in Bishopwearmouth Cemetery in 1965, the only significant remains were an embankment in the grounds of Grindon Library and Museum and the embankment in Fox Cover Wood. In 2003 the well of the Glebe Engine House was uncovered in the grounds of Sunderland Royal Hospital during building work and a circular brick structure was built at ground level around the shaft. This can be seen near the Chester Road entrance.

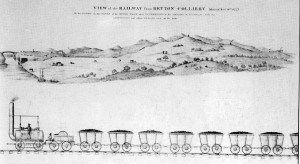

The Newbottle Wagonway was of major significance in the development of railways on Wearside, although it has overshadowed by the later, but better known, Hetton Colliery Railway which survived until 1959. The major changes made from a horse-operated to a rope-operated operated line during its first twenty years and its replacement by locomotive hauled trains over a public railway within sixty years were a reminder that technology developed rapidly during the 19th century.

The Hetton Colliery Railway opened in 1822 was the second railway to go from colliery direct to staiths at Sunderland. It was engineered by George Stephenson and was in some ways the precursor of his Stockton and Darlington Railway of 1825, although the S&DR was a public railway. The Hetton line used stationary steam engines and self-acting inclines, as the Newbottle line did but also steam locomotives on certain sections of the route.

14 Responses to The Newbottle Waggon Rail Way Map