It’s great to do some hands on research from time to time. There’s a bird skin in the collection that I’ve been looking at recently. This is a specimen of a bird called Horsfield’s Bronze Cuckoo. Holding it up to the light, the iridescent greenish bronze colour is still visible on the feathers of the bird’s back. Otherwise it’s small, brown and heavy barred underneath.

So, other than being a good example of this species, why is the skin of interest? Well, this is an Australasian bird, normally found on the Australian continent, as well as the Malay peninsular, New Guinea and some nearby islands. However, the record for this specimen indicates that this particular bird was collected in the Seychelles – a very long way across the ocean from Australia.

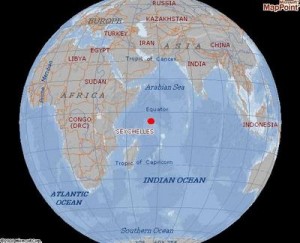

The red dot shows the location of the Seychelles. The landmass at the bottom right of the image is Australia.

It seems almost unbelievable that such a small thing could survive a journey of this vast distance. Holding the bird, it’s easy to feel some sympathy for it. There’s something incredibly compelling about the image of a tiny bird, far out at sea, flying on and on in search of land.

However, such journeys are surprisingly common. In the past, oil rig workers in the Gulf of Mexico were stunned to see swarms of ping-pong ball sized Ruby Throated Hummingbirds zipping past, hundreds of miles from the shore. We now know that this is the regular route of the birds’ spring migration. The recent visit of an Eastern Crowned Warbler to an old quarry on the coast near South Shields is another example of a small bird making a mammoth journey. Both these birds are a lot smaller than our cuckoo.

However, no one on the Seychelles has ever seen a Horsfield’s Bronze Cuckoo before or since. This bird is the only one ever recorded, and given that it’s such a long way from home, we really need to be sure that we’ve got the facts right.

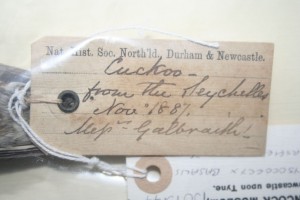

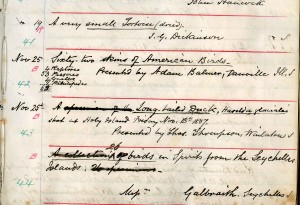

So, what’s the story of our specimen? The original label mentions a ‘Messrs Galbraith’. A look at the Accession Book from 1887 shows that this bird is one of a consignment of ‘26 birds in spirits’ donated to the Natural History Society of Northumbria by a ‘Mssrs Galbraith. Seychelles’. So far, so good.

So who were Mssrs Galbraith? According to Robert Prys-Jones of the Natural History Museum there was at least one Galbraith, a vanilla plantation owner called S.J Galbraith, living in the Seychelles in the 1880s. So it seems as if this man sent us his collection of birds in spirits (preserved in jars of alcohol), including the cuckoo. But the link between the bird, the man, the location and the collection is not crystal clear. Is the donor the man we know of, or someone else entirely? How did he come by the birds? Why did he give them to the society?

There’s another twist to this story. In a letter in the archives of the Natural History Society of Northumbria dated 25 Feb 1875, there’s a mention of a firm of London shipping agents called ‘Messrs Galbraith, Stringer & Pembroke.’ So, does the entry in the accession register actually refer to the shipping agents who delivered the birds from the Seychelles?

25 other skins were part of the same acquisition – can they help us get to the bottom of the mystery? A quick search reveals that all but three of these seem to have disappeared. The surviving three; two Seychelles Kestrels and a Seychelles Blue Pigeon are all endemic to the Seychelles. It’s therefore very unlikely that they where collected elsewhere.

So what can we say?

The original documentation suggests to us that this bird came from the Seychelles. Other specimens in the same acquisition certainly did. We know that someone called Galbraith was living there at the time. Although the bird’s regular range is a vast distance away, similar examples of birds turning up unexpectedly tell us that it’s not impossible the cuckoo made it that far. This would mean that our skin is really important, because it’s a unique record of this species from the Seychelles.

On the flipside, we can’t make a connection between this specimen and S.J Galbraith. A letter in the archive suggests that the name may refer to a shipping agent rather than the donor. There’s nothing that tells us the exact circumstances of the bird’s acquisition.

Somebody living in the Seychelles with connections to the society could have sent back a collection of birds containing a variety of skins they picked up on their travels, including a cuckoo from Australia as well as some local birds. The person writing in the accession book noted down the name of the shipping agent rather than the donor, and the error was copied on the label.

So did this little bird make an epic journey across the Indian Ocean or not? The cuckoo hasn’t given up its secrets yet.

One Response to The mystery of Horsfield’s Bronze Cuckoo