Hello, my name is Brian Allen and I am privileged to be a volunteer in the special and unique Great North Museum: Hancock Library. Welcome to my second blog about some of the amazing books that can be found here. I am also a member of the Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) which has its Library and Archives located here. Some of the books are on the open shelves whilst the older and rarer texts are kept behind the scenes in a controlled environment. Any of the material can be requested and the librarian will make it available for you to view. NHSN books in the public area can be loaned by members of the Society, which has its office just along the corridor from the Library.

My first blog looked at the Collins’ New Naturalists series and referred to the “Old Naturalists” in passing. This was not an ageist comment about members of the Society! It was rather an acknowledgement that the Library has a valuable collection of books going back centuries demonstrating how natural history was observed and recorded in the past. I mentioned Gilbert White (1720 – 1793) whose “Natural History and Antiquities of Selbourne” (1789) is a classic.

Gilbert White

The Library has an early edition (1813) of this collection of letters to friends recording White’s observations of the natural environment where he lived in East Hampshire. As a parson-naturalist-ornithologist he enjoyed a privileged life style which afforded him considerable freedom to pursue his own interests. His aim was to “…induce any of his readers to pay a more ready attention to the wonders of the Creation, too frequently overlooked as common occurrences…”. If he did not succeed in fulfilling this aim he acknowledged the physical and mental benefits of his pursuits into old age not least through engaging intelligently with others. Today we have citizen science, social media and the opportunity to share our interests with others in classes, on field trips and when visiting nature reserves. This shared passion soon leads to friendly conversations with others doing the same thing.

Gilbert White is not the only significant old naturalist to have been a clergyman. Indeed there are several other clergymen represented in the Library’s collection who made very significant contributions both regionally and nationally. I want to look at a few of them in the rest of this blog.

My first Old Naturalist is a 16th century local man with the reputation of being the “Father of Botany”. William Turner (1509 – 1568) was from Morpeth where a garden now commemorates this remarkable polymath.

William Turner Garden, Morpeth

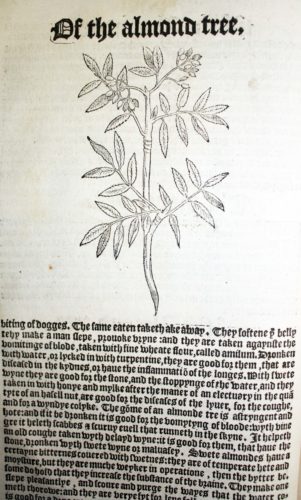

In those days clergy were often highly educated and from the type of backgrounds which made this possible. Turner, qualified in medicine and science, was no stranger to religious controversy as a Protestant Calvinist senior clergyman who became Dean of Wells Cathedral (1560 -1564). His major contribution to natural history is “A New Herball” first published in 1551. A rare first edition of this book is available in the NHSN library. I find it reassuring that he sometimes struggled in the task of identifying various plants. Despite the advances of science and popular publications it is still a tricky subject for me. Turner eschewed criticism and deliberately chose to write in English rather than in Latin, familiarly used in his day for academic and scientific writings. His argument was straightforward. He likened clergy who taught in Latin to warn their flocks of the perils of this life to a watchman on the walls of Berwick. On seeing the Scots approaching a warning shouted in Latin “Veniunt Scoti” would not be heeded and the Scots would take the town! “Were he not worthy to be hanged for this labour?” asks Turner. Turner followed the convention of using Latin when classifying plants and drew on ancient texts, nonetheless. His illustrations were from woodcuts by the German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs whose own book in Latin was first published in 1542. They may not always be a reliable guide to identification, but it is possible, apparently, to identify plants today from many of those pictured in the Herball.

A page from “A New Herball”

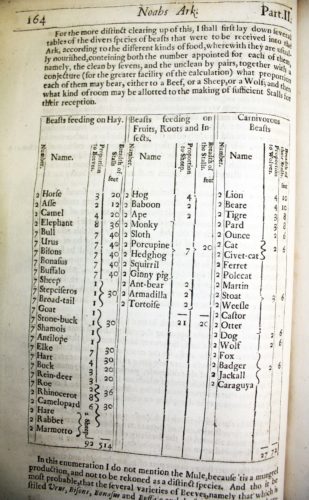

If you visited the Library when Dippy was in residence you might have seen a copy on display of John Wilkins (1614 – 1672) and John Ray’s (1627 – 1705) “An essay towards Real Character and a Philosophical Language”. This was published in 1668 and attempts a systematic approach to all that was known about the world at that time. This included a fascinatingly arcane example when applied to the Bible account of Noah’s Ark. The description of how all the animals would have fitted into the ark comes with lists and an illustration.

Noah’s Ark List of Animals

Wilkins was clearly regarded as an important intellectual clergyman of his day. He had the unusual distinction of having been head of colleges at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, became Bishop of Chester and was a founder of the Royal Society of which he was made a Fellow.

My next old naturalist is John Wallis (1714 -1793). He was a curate at Simonburn in the North Tyne valley for some years and published in two volumes “The Natural History and Antiquities of Northumberland…” in 1769 also in the NHSN library. The first volume describes minerals, fossils, plants and animals and the second volume follows three tours around the county. Both volumes are selective in their contents. For example, in choosing which birds to mention, he focuses on the “most curious and uncommon” including what he calls a “penguin” which today we know to be a (now extinct) great auk.

When walking in Wallis’ footsteps around Simonburn earlier this year, we followed a brown hare along a lane for a minute or so before it ran across the fields. Wallis includes the brown hare in Volume One. He wished “…our young sportsmen would have more regard to their preservation, and their own pleasure and not hunt them down annually like wolves and bears, to be extirpated without mercy…for the pitiful and brutal ambition only of the boasting among their companions of their killing…Savage and inhuman butchery! Away with it from Northumberland!..”.

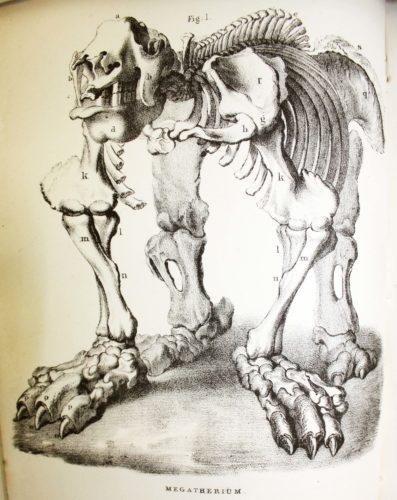

Another book displayed in the Library during Dippy’s stay was by William Buckland (1784 – 1856), the next old naturalist. He was a Reader in Geology and Mineralogy in the University of Oxford, a Canon of Christ Church, Oxford and later Dean of Westminster. His book “Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology” was published in 1836 and is in the NHSN Library. He did a lot of work on fossils and was the first English scientist to follow the glaciation theory of the Swiss-American biologist and geologist Louis Agassiz. Nonetheless he held the Biblical Flood to be the cause of all erosion and sedimentation as he sought to reconcile his findings with Biblical narratives. His work contains the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, now known as Megalosaurus.bucklandii, and is displayed in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. There are also fine illustrations of the skeleton of an extinct elephant sized sloth, endemic in South America, from the Early Pliocene to the end of the Pleistoscene.

Buckland Image

My final “parson-naturalist” is a son of the vicar at Eglingham, Northumberland, Henry Baker Tristram (1822–1906). Like his father he became ordained but travelled very widely, especially in the Near East, North Africa and Japan whilst Rector of Castle Eden in County Durham. He became a Canon of Durham Cathedral and a Fellow of the Royal Society. He found the theories about evolution expounded by Darwin and Wallace initially most persuasive. On considering a “series of about 100 larks of various species before me…” he claimed “…I cannot help feeling convinced of the views set forth by Messrs Darwin and Wallace” (Ibis 1859). He changed his mind later following a debate which took place in the Oxford University Natural History Museum. Tristram was a founder of the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) in 1858 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society. The BOU is one of the world’s oldest and most respected ornithological organisations with membership stretching across all continents and publishes “IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science” which is available in the NHSN Library. Being handy with a gun as many collectors of ornithological data were then, he gathered a large collection of bird skins which he later sold to a Museum in Liverpool. The Library holds a copy of Tristram’s book “The Natural History of the Bible, being a review of the physical, geography, geology and meteorology of the Holy Land, with a description of every animal and plant mentioned in Holy Scripture” (1867).

Some of the world views behind these writings may well seem remarkably at odds with contemporary science. However, these old books bear witness to several centuries of “parson-naturalists” taking very seriously the business of observing and recording their encounters with the natural world. They were not merely exercising a casual interest or practising what we might call today a hobby. They were intelligent, skilled and dedicated men whose legacy is to have contributed to the foundations of our understanding and exploration of natural history today. Women and men of all ages and from a wide range of backgrounds engage in the study of natural history today, whether as professionals or amateurs (that is, those who love the subject). Many more books have been written and will continue to be published to contribute to the growth of our understanding of nature. Some of them are to be found in the Great North Museum: Hancock Library which also houses special displays from time to time. Do come and explore these riches for yourself!

The Library is free to use and open to everyone. Further information can be found at https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives

Our ethnographic collection has originated from many different sources. Explorers, missionaries, other museums – we’ve been accepting interesting objects from around the world for centuries. During my time researching the North American collection, I’ve discovered that some of the objects from Arctic regions have a direct link with an industry that Newcastle upon Tyne used to be famous for: whaling.

Nowadays, commercial whaling is banned by many countries including the UK, but 250 years ago, whaling in Arctic waters was big business. Whales were hunted in vast numbers mainly for their oil which was used in a variety of products at the time and was highly valued as an illuminant. Newcastle was a focal point for whaling activity in the northeast of England, often rivalling the great whaling port of Whitby. Even when British whaling began to decline in the 1820s, Newcastle still had a fleet of whaling ships that would venture to the Arctic waters near Greenland- sometimes returning back to the River Tyne with some very interesting souvenirs that they had traded for with the local Inuit.

Whalers Entering the Tyne by John Wilson Carmichael. Credit: Torre Abbey Museum

The Lady Jane was a 313 ton ship originally built on the Thames in 1722. By 1804 she was Newcastle-based and became a highly successful whaler. In 1827, the Literary & Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne was given three objects that had been brought back from arctic waters on the Lady Jane by its commander, Captain Fleming.

NEWHM : G116, oil scoop

NEWHM : G115, adze

NEWHM : 1998.H250, lamp

These implements gave the people of Newcastle a rare glimpse into Inuit life. The adze in particular is of interest, due its metal content. Iron was rare in the northern Arctic regions, but Inuit would salvage any kind of metal from shipwrecks, which is what appears to have happened with the adze. It is thought to have been made using the mast hoops from the Aurora or Dexterity – ships that were wrecked on the west coast of the Davis Straits in 1821.

The Lady Jane appears in museum records once again 10 years later. In 1837, Captain James Leask donated a full size Inuit kayak complete with oar, hunting implements and a sealskin float.

Captain Leask’s kayak and hunting equipment on display in the World Cultures gallery.

They are wonderful objects and enable us to see first-hand the high degree of skill needed by Inuit to create vital pieces of hunting equipment. While they are remarkable historical artefacts, the fateful story of their collection is somewhat harrowing. The Lady Jane had set sail in 1835, but by December the ship was frozen in sea ice near Greenland. The ship finally returned to Newcastle in March 1836, by which time 27 of the crew had died from scurvy and other illnesses. The deprivations the ship’s crew underwent during that winter was dreadful. James Williamson from South Shields was a young doctor on board during this time, and his journal notes many harrowing experiences. On his return to Newcastle, Captain Leask was accused of incompetence by his surviving crew. Although a public enquiry was conducted into the disaster, Captain James Leask was completely exonerated of all charges.

Another famous Newcastle whaling ship also appears in museum records. The Lord Gambier was brought into the whaling trade in 1831. At 407 tonnes, she was an even bigger vessel than the Lady Jane. Captain Richard Warham was commander of the Lord Gambier and he brought back many artefacts and specimens from his voyages to the Arctic, including a beautiful Inuit seal skin shoe, and more famously Eric the Polar Bear.

Captain Richard Warham. Credit: NHSN

NEWHM : M0934, Polar Bear on display in Living Planet gallery. Shot by a crew member of the Lord Gambier in the Davis Straits, off Greenland, 1835

NEWHM : G111, Inuit shoe

By the early 1840s, the whaling industry was in serious decline on Tyneside. The market for whale oil was decreasing and there had been too many disasters in Arctic waters where ships had been crushed by sea ice. Combined with a dramatic fall in whale numbers around Greenland, it meant that too many voyages were unproductive, forcing ship-owners to review their trade. By 1842, the Lord Gambier had been withdrawn from whaling activities along with another Tyneside-based whaler, the Grenville Bay, leaving the Lady Jane as the only active whaling vessel operating from Newcastle. She was destroyed in 1849, crushed by sea ice on her final whaling voyage.

The Lord Gambier, Lady Jane and Grenville Bay whaling in the Arctic, by John Wilson Carmichael

The Inuit material that whaling ships brought back to Newcastle are powerful historical objects, offering us an insight into a way of life that existed 200 years ago for the peoples of the Arctic regions. Little could the Tyneside whalermen know all those years ago that the “souvenirs” of their voyages would be so important and highly regarded in the 21st century.

This research was made possible by a Headley Fellowship

Folk songs often tell the stories of everyday people. They expose counter narratives to accepted history and allow personal connections to be made across time, age and class. I have been involved in folk traditions my whole life; the stories of industry, war and the hardiness of the people of the North-East that I have listened to through my involvement in the UOSH project fit in perfectly with the narratives I hear so often in traditional songs. While I already knew of the immense change that had occurred between 1900 and 2000, these recordings highlighted how this change affected everyday lives – from the difference in schooling and technology, the effect of rationing and bombing in the North-East during WW2, to the development in attitudes toward married women working.

Rose listening to an oral history recording from the TWAM collection

In reflecting on my own position in life, listening to these oral histories emphasised to me how little I knew about my parent’s or grandparent’s lives before I was born. I knew of their occupations and I knew broadly of their family life but that was all. In hearing stories of caning in schools, I wondered if my father, born in 1949, had experienced this. He told me he had. And it was accepted as normal. I reflected on my own schooling, thinking particularly of one teacher who terrified the younger students and I wondered how much worse it would have been if he had been allowed to cane them. I listened to the story of a woman who, at 17, moved from Pakistan to England and was made to work for her mother-in-law and given little freedom. Consequently, I reflected on things my mother had told me about sneaking out of her room as a teenager to go out with friends. And considered the freedom she then gave me as I was growing up. Listening to this woman discuss the breakdown of her marriage and having to learn, as an adult, to do everything independently is another example of the resilience of previous generations which shines through in these recordings. Despite the hardships of these people, their enjoyment of life is also evident.

Grand Parade passing along Scotswood Road, celebrating the Centenary of the Blaydon Races, 9 June 1962. TWAM ref. DS.VA/9/PH/3/8

On hearing how another man moved to Newcastle and set up his work in the Ouseburn valley (an area I have come to know and love), the change from industry to arts in the area was highlighted and I began to reflect on what change has occurred in Newcastle in the time I have lived here. Regeneration has been a key topic of conversation in many of these recordings – some focusing positively on the development of previous industrial sites and others negatively on building for profit without the consideration of local communities. Despite only living here since 2015, I have seen the rapid development and building of student accommodation and the opening of new pubs, restaurants, cafes and art spaces (some of which make use of old industrial spaces). These recordings and my own experience illustrate how rapidly cities can change and make me wonder what change will come in the next 100 years.

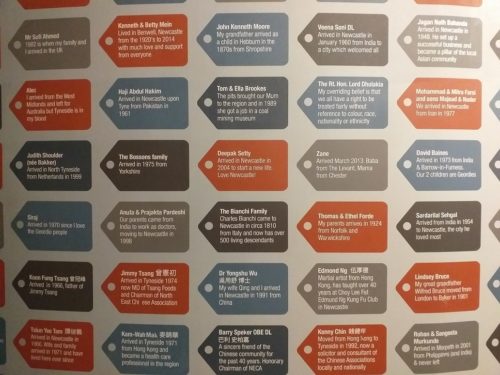

This wall of luggage labels can be found in the Destination Tyneside gallery in Discovery Museum and highlight some of the individuals who have made Tyneside their home.

These sound recordings don’t just tell the story of the North-East, they tell the story of people from varied backgrounds who have all come to see this area of the world as their home. They consistently emphasise the friendliness of the people of the North-East, something I have experienced so often in the nearly 4 years I have lived in Newcastle. They highlight the importance of community – from the friendships women made as war workers to the rallying of residents in fighting government plans to demolish their housing estate. Most importantly, these recordings can highlight all these aspects within the lives of listeners. They can inspire and motivate, make you grateful for what you have and determined to fight for what you don’t. I have loved listening to these recordings and am happy knowing that my work in cataloguing them brings them a step closer to being accessible online. The work that is being done on the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project will allow many others to learn about the North-East’s past through the eyes of everyday people, to reflect on the present through this past and, hopefully, to love listening to them as much as I did.

Making micante sheets (1914 – 18). This image is from the Parsons’ ‘Women Labourers’ photograph album, taken at Parsons’ Works on Shields Road during the First World War. TWAM ref: 2402.

Rose was a placement student in the summer of 2019. If you are interested in undertaking a placement with the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage Project, we have availability throughout the year. Please register your interest at volunteering@twmuseums.org

Unlocking Our Sound Heritage is funded by a grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, as well as generous funding from charities and individuals. The project is led by the British Library. To read more please see https://twarchives.org.uk/unlocking-our-sound-heritage

![]()

Hello, My name is Brian Allen and I am a Volunteer at the Great North Museum: Hancock Library.

When you visit the Great North Museum: Hancock allow time to discover the library if you have not already done so. It is not exactly a secret but it is not as well-known as it deserves to be. Here are collections belonging to the Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) as well as the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne and the Cowen Collection of Newcastle University’s School of History, Classics and Archaeology.

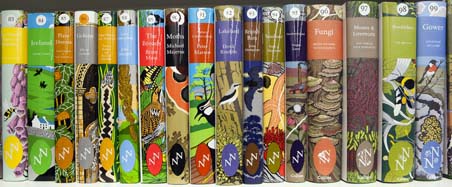

On your first visit it is probably best to take the lift to the second floor and there is the library immediately on your left! Step inside and one of the most eye catching sections is soon to be seen on your right. It is the complete set of the Collins New Naturalist Series with their outstanding dust jackets.

The New Naturalist series is published by Collins on a variety of natural history topics relevant to the British Isles. The aim of the series at the start was “to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalists.” This highly prized collection began being published in 1945 when the first in the series was E. B. Ford’s “Butterflies”. The most recent addition, “Gulls” by John C Coulson, was published in April this year as number 139 in the series. The complete set including twenty two monographs are for reference only and can be enjoyed in the library by everyone. There are some duplicate copies available for members of the Natural History Society of Northumbria to borrow on presentation of their membership card.

From the outset the editors believed that the British public’s natural pride in our native fauna and flora, as well as concern for conservation, would be best fostered by presenting the results of modern scientific research with a consistently high standard of accuracy and clarity.

The Old Naturalists

The new naturalists were and are experts in their chosen field and mainly scientists but who were the old naturalists and what remains of their observations and writings?

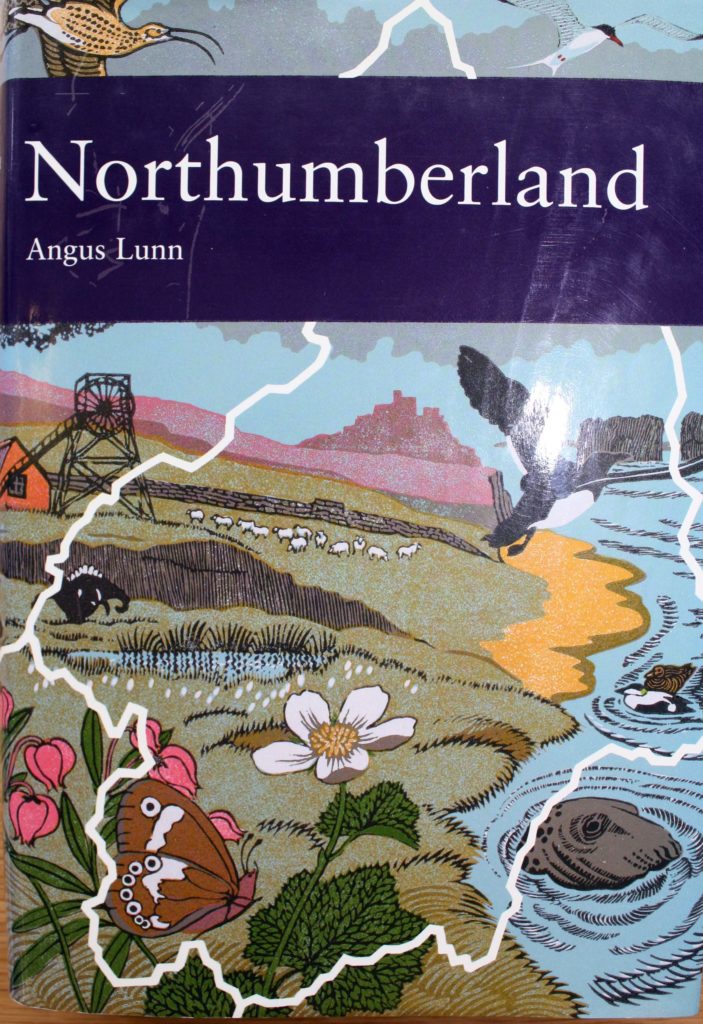

You might think of Gilbert White and his “The Natural History of Selborne” (in east Hampshire) as an example of an old naturalist in this context. However, there are many examples more local to our region. Northumberland was the first county to be covered in the New Naturalist series when local naturalist Angus Lunn’s book was published in 2004. The editor’s preface refers to some of the region’s old naturalists including the 16th century William Turner, the 18th century John Wallis, Nathaniel Winch and Thomas Bewick both spanning the 18th and 19th centuries, Prideaux John Selby and John Hancock both of the 19th century, and Abel Chapman and George Bolam spanning the 19th and 20th centuries. The NHSN has some fine examples of the work of these “old” naturalists in the library’s valuable restricted access collection and archives available to readers on request. I will be working on a future blog about this topic.

All the old naturalists cited above are men. Out of nearly 200 New Naturalist authors and co-authors only 7, that is less than 4%, are women.

Topics covered by the New Naturalist Series

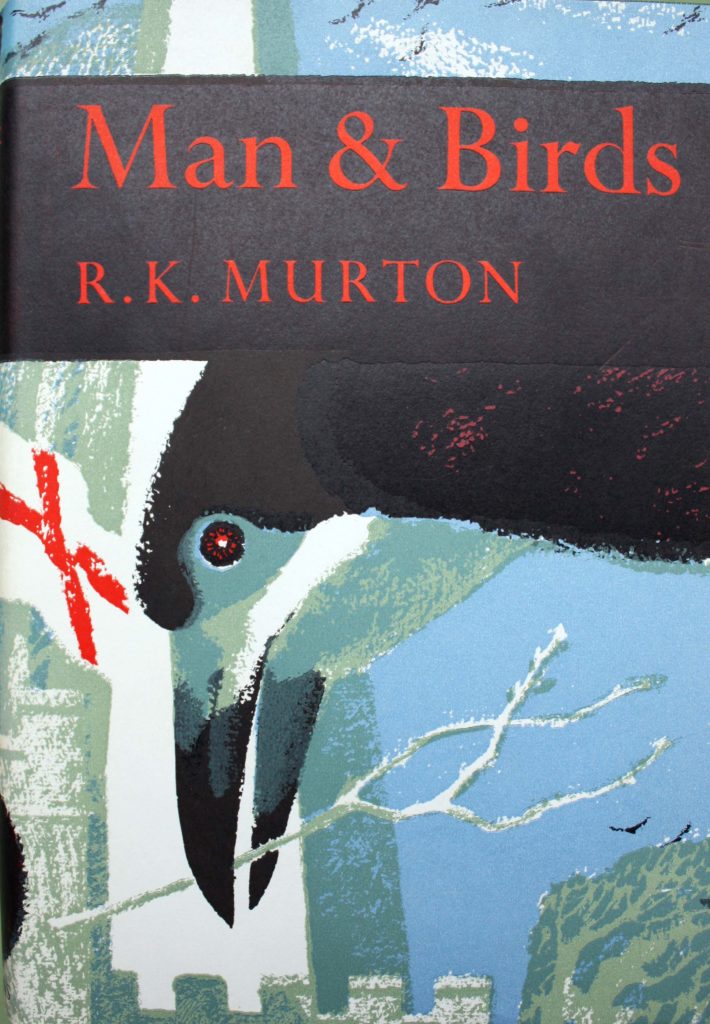

A wide range of topics dealing with large groups of animals and plants have already been covered in this globally significant series. Sitting alongside it, or more accurately in our library beneath it is the smaller monograph series which focuses on an individual species or group of species, mainly but not exclusively birds. In the editors’ preface to a 1952 monograph they write “An object of the New Naturalist series is the recognition of the many-sidedness of British natural history, and the encouragement of unusual and original developments of its forgotten or neglected facets.” There have been no additions to the Monographs since 1971.

Art work dust jackets

One distinctive feature that makes this collection so attractive is the design of the dust jackets. For many years these distinctive designs were created by a couple, Clifford and Rosemary Ellis identified in their work as C & R E. They used offset lithography, a technique in which they were very skilled. Their designs were regarded as works of art in their own right so experienced art printers were employed rather than the House of Collins despite it being a printer as well as a publisher.

Later designs from 1985 are by Robert Gillmor, known to many for his characteristic bird illustrations. He too worked closely with experienced art printers initially using much the same technique as C & R E had. He changed later to using linocuts to increase the colours’ vibrancy. Eventually the printers wanted “camera ready artwork” and the printing took place in Thailand. No longer could the artist work with the printers to the same effect.

Robert Gillmor first experienced the changes in 2004 with the design for Angus Lunn’s Northumberland (Number 95 in the series). He describes the experience in “The Art of the New Naturalists” (Marren & Gillmor, Collins 2009) when the county outline was misplaced by 4mm to the right leaving a line cutting through the seal’s head, covering some of the wing of the butterfly and obliterating the head of a blackcock. He was not happy! He had already revised his design to reduce the number of birds featured which meant removing a prominent image of a ring ouzel. The final version is designed to show the diverse features of the county’s landscape, with its flora and fauna all connected by the outline of the county. My own paperback copy has a photograph of a rural landscape without any fauna on its cover!

The series continues to be published with forthcoming titles to include “Garden Birds” and “Pembrokeshire”. It will be interesting to see just how the 75th anniversary of this unique series will be marked in 2020. What might the topics be and will there be more women naturalists amongst the authors?

There is an increasing sense of crisis amongst conservationists and naturalists given the impact of climate change on the planet and all its inhabitants. David Attenborough, amongst others, has highlighted the pressing issues. Extinction Rebellion is a growing movement globally and the sixteen year old Swedish school student, Greta Thunberg, has been powerfully prominent and eloquent on the international stage, too. Will a newer breed yet of New Naturalists, female and male, emerge in this climate?

The Great North Museum: Hancock Library is free to use and is open to everyone. It is located on the second floor of the Museum. Further information can be found at https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives