Hello, my name is Leah Newbigging and I have been undertaking research using the collections in the amazing library of the Natural History Society of Northumbria. This is located in the Great North Museum: Hancock Library which is free to use and open to everybody. All of the books I mention below are located in the GNM: Hancock Library.

My preoccupation with “the North” began when I was at university, studying the music of the Icelandic artist, Björk. (When I use the term “the North” I am generally referring to regions in the Arctic Circle, including Scandinavia, Greenland, Canada and Russia.) At the time, I was writing about how she uses and refers to nature in her music; she used recordings of footsteps in the snow as percussion, and created deep, distorted noises to emulate the sound of volcanoes erupting to evoke Icelandic landscapes. I went on to do a master’s degree where I researched musicians in Northern regions who use Northern landscapes to build a brand based on their national or regional identity. This is not a new practice by any means – countries have drawn upon their natural scenery for their national identity for centuries, particularly in the 19th century Romantic era.

The more I listened to musicians who branded themselves as “Northern”, the more I began to notice that there were common themes in audience reactions, often referring to something pure, simple, authentic, and primal. I needed some guidance in understanding how the North has been portrayed and imagined historically, in order to understand why people reacted to Northern landscapes in this way.

This is where Peter Davidson’s book “The Idea of North” (2005) came in. Davidson writes about how Northern landscapes have been portrayed in myth, poetry, literature and film, ranging from Nabokov’s Zembla, the Old Norse sagas, Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” (the inspiration for the film “Frozen”), to Dutch and German Romantic landscape paintings, and accounts of Arctic expeditions.

Davidson describes how the North has often been used as a metaphor for the edges of the known world; its remoteness and difficult climate mean that the North was often framed as a challenge to be explored and conquered. Portrayals of the North generally fell into two categories, often with moral undertones; the North as a place of death, and the North as a place of beauty and purity.

The television series “Game of Thrones” and the film “The Revenant” are modern examples of portraying the North as a place of death and monotony; long, cold dark nights, storms, isolation, decay, and the dead walking again (called draugr in Norse mythology, and now commonly referred to as revenants from the French for “to come back”). Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen”, as a sort of embodiment of winter, was originally meant to function as a warning against the perils of social isolation and selfishness, since survival often depended on being able to cooperate and pool resources. Of course, the perception that winter landscapes are devoid of life is primarily us projecting our fears, as winter biomes are still rich with life under the snow.

On the other hand, you do not have to look far for modern portrayals of the North’s beauty, between the many musicians, travel agencies and Instagram accounts who rely on images of these landscapes. This portrayal of Northern landscapes tends to focus on snow, ice, glass, snowflakes, and the midnight sun. In Ancient Greek and Roman mythology, the Hyperboreans were mythical people who lived in a perfect land of untouched nature constant sunshine to the far North; this land was referred to as “Thule” or “Ultima Thule”, the edge of the known world. This meant that travellers would often arrive in places such as Shetland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway and Greenland with expectations of a land of beauty and purity, only to be confronted by poverty and the reality of surviving on subsistence agriculture.

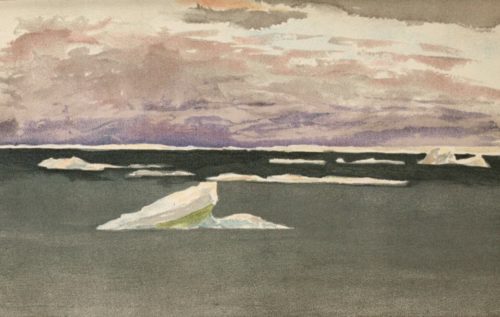

“Off the Edge of the Ice – Gathering Storm, 14 September 1893” from Fridtjof Nansen’s “Farthest North”

For anyone who has an interest in reading about human relationships with Northern landscapes, this book is a thorough and fascinating account of the ways we have historically portrayed Arctic scenery and culture. It provides an insight into each work of literature, so we can understand the period of time the author was writing in and how this influenced the way they think of the North.

The musicians I focused on during the research for my Master’s degree heavily relied on these historic portrayals of Arctic scenery and culture. For example, many musicians in the Faroe Islands chose to brand their music with images of a mythologised pre-Christian, Viking, pagan North, including stereotypical Northern landscapes such as snowy mountains, and a cultural mishmash of symbols of paganism such as drums, feathers and bones, and nature such as the sun and moon.

I started to understand that the images of the North we still have today are saturated with a long history of authors, travellers and outsiders shaping the way we imagine “the North”. Scientific, missionary and trade expeditions were a common feature of European exploration and colonialism. The travellers would write about their experiences visiting far-off, exotic lands, often describing the landscapes and culture in terms of morality, such as purity or barbarity. Eventually I found a plethora of Scandinavian scholars who confirmed my suspicions that contemporary explorers perceived the North as another “Orient” to be conquered; as exotic, dangerous, wild and alluring as the Asian or African places they would visit, only colder and whiter. (You can find my citations at the end of post).

There is certainly no shortage of first-hand reports that help to corroborate this claim. British travellers like Richard Burton, Anthony Trollope, Mrs Alec Tweedie, Sabine Baring-Gould and William Morris all ventured North to try to find Ultima Thule. Morris even wrote in his accounts that he was undergoing “a Viking adventure”, and that the Faroese land was his first experience of the true North.

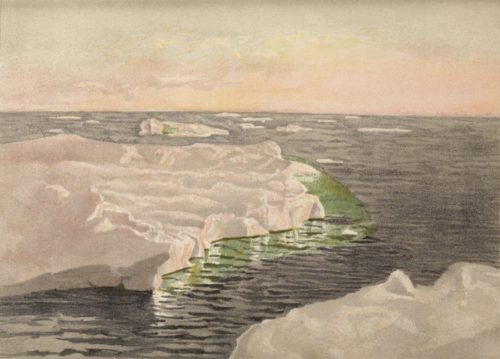

“At Sunset, 22nd September 1893” From Fridtjof Nansen’s “Farthest North”

I continued my search and found many similar accounts in the NHSN library which contains original 19th and early 20th century books and journals about scientific expeditions to the Arctic. Dr Fridtjof Nansen begins his account of their expedition rather dramatically in his book “Farthest North…” (1897)

“Unseen and untrodden under their spotless mantle of ice, the rigid polar regions slept the profound sleep of death from the earliest dawn of time. Wrapped in his white shroud, the mighty giant stretched his clammy ice-limbs abroad, and dreamed his age-long dreams. Ages passed – deep was the silence.” (page 1)

He continues talking about Norse mythology, mentioning frost giants, Niflheim (or Nivlheim as he spells it), Helheim and Baldur, and in a similar fashion to William Morris, Nansen frames himself as a Viking explorer by mentioning that the old Vikings were “the first Arctic voyagers”. His writing is also a perfect example of the colonial conquering tendencies so prevalent in 19th century Europe:

“The spirit of mankind will never rest till every spot of these regions has been trodden by the foot of man, till every enigma has been solved.” (page 3)

His attitude is echoed by other writers when they describe the native inhabitants of Greenland (then called Eskimo, but now Inuit), characterising them as naïve and simple, or barbaric. It is rather uncomfortable to reproduce what they say in a modern setting, but as an illustration, Aubyn Trevor-Battye’s book “Ice bound on the Kolguev…” (1895) describes the “happy, good-tempered character of these child-like people” (page 242). When describing the native inhabitants’ navigational and hunting techniques, almost all of the writers I reviewed for this article lean heavily into the idea that the Inuit are more closely connected to nature and are a simpler people than their European counterparts.

The above examples are indicative of the way that the travellers wrote about both the landscape and the native inhabitants, containing many similarities in themes that focus on purity or danger as I mentioned earlier. Many of the authors have a love-hate relationship with ice in particular. Ejnar Mikkelsen, in his book “Lost in the Arctic…” (1913), describes how they are in near-constant danger of their vessels being caught, crushed or sunk by the ice, in what is by far my favourite quote:

“Thoroughly disgusted with things in general, and unanimously agreeing that ice and the Arctic were hell upon earth, we were at last obliged to make fast.” (page 24)

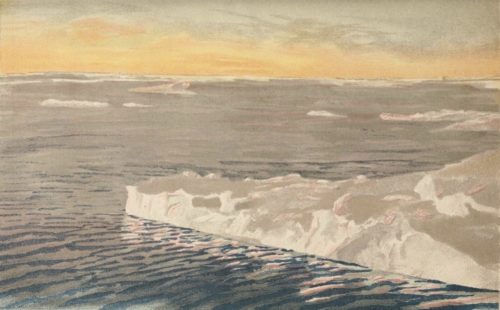

“Evening Among Drift Ice” From Fridtjof Nansen’s “Farthest North”

Another common gripe that many of the authors have with the Arctic landscape is the monotony, extreme days and nights, and the perceived lifelessness:

“It was certainly about as miserable and uninviting a coast as you can well imagine. Trees you cannot expect to find in these latitudes, but often their absence is more than made up for by beauty of scenery in other ways – in splendour of glacier or strength of the bastion cliffs across which the sea-birds go in myriads like driven snow. Here we had not this. We had only a long low line of level monotony.”

Trevor-Battye, Ice-bound on Kolguev (page 32-33).

“The sameness of everything weighted on the spirits… On the land there was nothing of picturesque to admit of description: the hills displayed no character, the rocks were rarely possessed of any, and the lakes and rivers were without beauty.”

Sir John Ross, Narrative of a Second Voyage (page 598).

“This snowless ice-plain is like a life without love – nothing to soften it.”

Fridtjof Nansen, Farthest North (page 297).

And yet also found are reverent descriptions of the very same ice, snow and sun in the same texts, echoing the distant and otherworldly conceptions of Ultima Thule.

“There was life enough up here among the pack ice – life and natural beauty, and splendid colour beyond words”.

“For an hour we lay motionless, staring at the ice, which lay there, an unchanging, dazzling expanse of white as far as the eye could see.”

Ejnar Mikkelsen, Lost in the Arctic (pages 22 and 27).

“A beautiful sight, the level, slightly drifted snow plain stretching away apparently infinitely to the North.”

“The slender spars of the [ship] looked very, very beautiful in the yellow midnight May sunlight.”

Robert E. Peary, Nearest the Pole (pages 109 and 167).

“The beauty of the scene before us [the mountainous coast] is much enhanced when the sun circles low to the south, we then get the most delicate blue shadows, and purest tones of pink and violet on the hill slopes.”

Sir Clements R. Markham, The Lands of Silence (page 464).

“The aurora appeared with more or less brilliancy on twenty-eight nights in this month, and we were also gratified by the resplendent beauty of the moon.”

John Franklin, Narrative of a Journey (page 257).

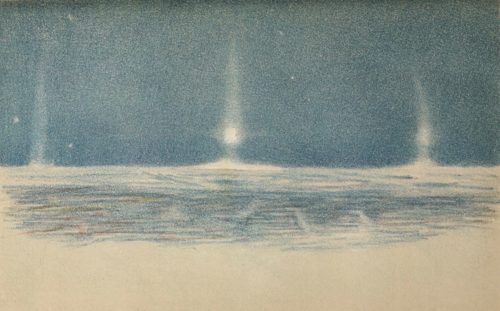

“Moonlight, 22 November 1893. A Vertical Axis Passes through the Moon with a Strongly-Marked Luminous Patch Where it Intersects the Horizon…” From Fridtjof Nansen’s “Farthest North”

One of my favourite things about studying history in libraries and archives is that it is possible to learn from the past so that we can evaluate how our current culture reacts to Northern landscapes. For example, the recent growth of Germanic neo-paganism and heathenry* and white nationalism continues the 19th century Romantic tradition of tying nationality to ethnicity and land. Amongst these demographics, Northern landscapes tend to function as an exotic place of escapism, where you can find sanctuary from modern life and contemporary values with regards to gender and race, so life can be lived in a simpler way (check out my citations at the end). When I was researching musicians who brand themselves by using images of Northern landscapes and paganism, I noticed that online audience reactions made frequent references to “true European culture” and “protecting European culture from external influences”. Some commentators went further and specified which external influences they wanted to keep out. This strongly echoes the ethno-nationalist and racist ideologies that were present when people like Wagner and Tolkien originally took inspiration from the Old Norse Sagas to start forming the fantasy genre as we know it today. An occultist, völkisch group called the Thule Society, founded in Germany in 1918, theorised that Thule was the lost homeland of the Aryan race, believed in the power of runes, and made all members swear that they had no Jewish or otherwise non-white heritage. One man who attended these meetings, Dietrich Eckhart, would go onto be a key influence on Hitler in his rise to power years later.

Thule (or Ultima Thule) is just one example of how a fictional landscape can capture the imaginations of people for hundreds, or even thousands of years. When I first started investigating the North, I was searching for an answer as to how and why people connect with images of the North in a strictly modern context. Having since spent the better part of a few years delving into this subject, I now know that I wouldn’t have achieved a nuanced understanding of contemporary cultural reactions and their significance without being able to view and consider relevant material from the past.

So, if you can, pay a visit to the Great North Museum: Hancock Library where you can read stories and accounts that were written by people from earlier times. You might find yourself recognising something of the modern-day in what they have to say.

Further information about the library is available at https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives

References

Resources external to the Great North Museum: Hancock Library.

Gaini, Firouz, ‘Cultural Rhapsody in Shift: Faroese culture and identity in the age of globalization’ in Among the Islanders of the North, ed. Firouz Gaini (Tórshavn: Faroe University Press, 2011), 132-162.

Granholm, Kennet, ‘“Sons of Northern Darkness”: Heathen Influences in Black Metal and Neofolk Music’, Numen, 58/4 (2011), 514-544.

Heesch, Florian, ‘Metal for Nordic Men? Amon Amarth’s Representations of Vikings’ in The Metal Void: First Gatherings, ed. Niall W. R. Scott (Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010), 71-80.

Hicks, Jonathon, Uy, Michael, Venter, Carina, ‘Introduction: Music and Landscape’, The Journal of Musicology, 33/1 (2016), 1-10.

Loftsdóttir, Kristín, ‘The Exotic North: Gender, Nation Branding and Post-colonialism in Iceland’, NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 23/4 (2015), 246-260.

Loftsdóttir, Kristín, Lund, Katrín Anna, ‘Þingvellir: Commodifying the “Heart” of Iceland’ in Postcolonial Perspectives on the European High North: Unscrambling the Arctic, ed. Graham Huggan, Lars Jensen (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 117-141.

Oslund, Karen, ‘Imagining Iceland: Narratives of Nature and History in the North Atlantic’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 35/3 (2002), 313-334.

Piotrowska, Anna G., ‘Scandinavian Heavy Metal as an Intertextual Play with Norse Mythology’ in Music at the Extremes: Essays on Sounds Outside the Mainstream, ed. Scott A. Wilson (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2015), 101-114.

Ridanpää, Juha, ‘Laughing at Northernness: Postcolonial and Metafictive Irony in the Imaginative Geography’, Social & Cultural Geography, 8/6 (2007), 907-928.

3 Responses to Images of the North – A Guest Post by Leah Newbigging