This is a guest post by Gil Dye, a volunteer at Discovery Museum.

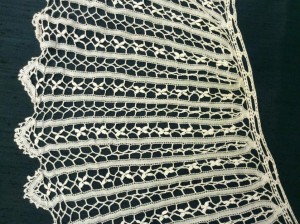

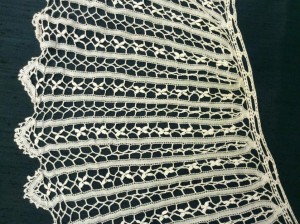

Branscombe Point collar, ref – TWCMS_H2387

Tape Lace

Branscombe Point is a tape lace that was first made in the Devon village of Branscombe around 1860. This was at a time when lace makers, who had traditionally worked fine Honiton lace, were needing new ways of competing with the growing machine-lace industry.

From the seventeenth century onwards the lace-making process has been speeded up by the use of pre-made tapes; the tapes prepared by tacking to a backing then linked; usually using a needle and thread to stitch the tapes together and often to work needle-lace bars and fillings.

Initially the tapes were worked with bobbins or hand-woven on narrow looms. Laces made with these tapes are sometimes referred to as mezzo punto. Below is a copy of a seventeenth century lace in the V&A, assembled from lengths of bobbin-made tape.

From the middle of the nineteenth to early in the twentieth century there was an explosion of interest in tape lace with manufacturers producing patterns and a wide range of machine made tapes (below).

Copy of 17th century lace made by author with bobbin-made tapes

Amateurs could buy a kit consisting of a pattern printed on glazed cotton together with any tapes, thread, padded rings (couronnes) and picot edgings needed to complete the collar, mat or other item. Patterns were also published in ladies’ magazines of the time. Shop assistants were expected to work at these patterns during quiet moments, both to produce items to sell and to show customers how the work was done. However it is clear that customers did not realise how much work was involved, since many part-worked projects remain in sewing boxes and turn up in collections (below).

Samples of 19th century machine-made tapes (author’s collection). A part-worked collar with pattern printed on glazed cloth and some of the tape that would be needed to make the collar. Lengths of ‘petal’ tape have been stitched in place and linked with needle-made bars; one area has been frilled with button-hole stitches. Also printed on the cloth is the name of the pattern – L’Henriette – and the code numbers – 439 and 718 of the tapes to be used (Author’s collection)

The generic name for all tape laces is Renaissance lace. Some laces rely for their effect on a variety of tapes, others on a variety of filling stitches. Tape-based laces were produced commercially in cottage industries in places such as Boris in Ireland and Ballantyre in Scotland in addition to Branscombe in Devon – and there are distinctive laces that bear these names. Around forty other names appear in magazines, advertising and other literature and it is not always possible to determine whether these are distinct styles or just a promotional brand.

The Technique of Tape Lace provides extensive information on tape lace from around the world, including working methods and 140 stitches (written by Ineke van den Kieboom and Annny Huijben, published by Batsford in 1994 with text in English, French and German, ISBN 0 7 134 6991 9).

If in doubt about the structure of a lace it is always worth looking for a tape.

Some examples:

In TWCMS_H1280 (below) the outlines are formed from a tape with one straight edge and one picoted. This is a carefully-planned piece with a variety of well worked fillings.

Tape lace collar, ref -TWCMS_H1280

Detail of a tape and crochet lace yoke – TWCMS_J8104

Above is a section of the yoke for a child’s dress (TWCMS_J8104). This is composed of one wide tape consisting of a series of flower shapes, each with ten petals (on the right of the picture) and several narrow cords with picots, which form the scallops on the left. The cords are linked with simple crochet stitches. This is another well-worked pieced giving a very professional finish.

TWCMS_H3235 (below) is part of a large tape lace collar, this has plain woven tapes, a crochet edging and crochet fillings mimicking simple bobbin lace.

Detail of a large tape collar with crochet fillings – TWCMS_H3235

The rather scruffy lace below (TWCMS_H1220) is a poor copy of fine Honiton lace; the main part does appear to be Honiton bobbin lace, while the neck edge is composed of two different machine tapes and all are linked by needle-made stitches. This combination of machine tapes and Honiton sprigs was at one time known as Damascene Lace.

Detail of an imitation Honiton collar – TWCMS_H1220

Princess Lace

Tapes can also be applied to machine net, sometimes alongside machine-embroidered motifs. This type of tape lace, now known as Princess Lace, is still made today, often sold as hand-made lace at airports and in tourist shops in Belgium and elsewhere – the ‘hand-made’ element is limited, usually consisting only of the large stitches used to attached the tape and motifs to the net.

21st century Princess Tape mat, Author’s collection

The mat above is an example of 21st century Princess lace. This is a well-made piece composed of three different tapes applied to fine hexagonal net – and possibly a fourth tape gathered to form the central rosette. Apart perhaps from the stitching threads, all materials are synthetic.

The lace below, part of a collar (ref: TWCMS_ H1280), is possibly 100 years older than the mat above. It includes seven different machine-woven tapes, plus motifs of chemical lace applied to a diamond net. It is likely that cotton thread has been used throughout. (Chemical lace is made by machine-embroidering a design with one type of yarn on to a fabric with a different chemical composition – eg cotton on silk – then dissolving the background. Embroiderers today use the same method on water-soluble fabric.)

Section of a large net collar with applied tapes and a chemical-lace motif. TWCMS_ H1280

Look out for more blogs by Gil, with highlights from the Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums lace collection.