Over the last few months I’ve had a chance to reflect on some of the fascinating authors whose works I encounter while performing my role as the librarian at the Great North Museum: Hancock Library. One of the names that crops up on a regular basis is that of William Chapman Hewitson. As well as being a writer on the natural world, his name appears as the benefactor who donated many of the rare books that belong to the Natural History Society of Northumbria’s wonderful library. For this blog I thought I’d undertake some research into Hewitson. This is what I discovered.

William Chapman Hewitson was born in Newcastle on 9 January 1806. From his early years he developed an interest in the study of the natural world that would become a lifelong passion. Among his friends were the marine biologist Albany Hancock and his brother John, taxidermist and naturalist. He also knew the zoologist Joshua Alder and the geologist William Hutton.

Hewitson was a founder member of the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle Upon Tyne which first met on 19 August 1829 and he played an active role in this organisation, becoming an Honorary Curator of Entomology. As a young man he had formed extensive collections of British coleoptera (beetles) and lepidoptera (butterflies).

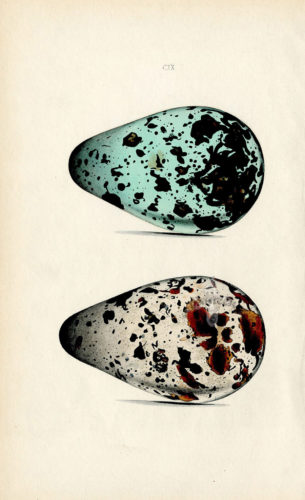

Another of his interests at this time was the study of birds and their eggs. The culmination of this work was the publication of “British Oology: Being Illustrations of the Eggs of British Birds, with Figures of Each Species….” published between 1831 – 1838. For this two volume work Hewitson personally produced the exquisite colour illustrations of the eggs that are included. It is also thought that the word “Oology”, meaning the study or collection of birds’ eggs, was first used in this publication.

Hewitson was also a keen and adventurous traveller at a time when such exploits could be fraught with risk and danger. In 1832 he undertook a journey to the Shetland Islands and in 1833 he and his friends John Hancock and Benjamin Johnson went on an expedition to Norway. Their object was to collect all kinds of natural history specimens, but more particularly to visit the breeding places of those birds which migrate to this country for the winter. They sailed from Newcastle in a Scotch brig and landed at Trondheim seven days later. Here they packed their baggage on a cart and set off on foot for the Arctic Circle. They suffered considerable hardship at times and often had to subsist on the birds they shot, but they reached their goal in safety. After spending three months in Norway they returned home bringing many treasures with them. Included in their collections were the eggs of the Capercaillie, Fieldfare, Turnstone, and Golden-eyed Duck which at that time were unknown in Britain.

In the summer of 1845 with his old friend John Hancock for his companion, he went on a naturalist’s expedition to Switzerland and the Alps, where he obtained, by a combination of capture and purchase, a fine series of diurnal lepidoptera, and the materials for a paper upon them which he contributed to the journal “Zoologist”.

During this same year Hewitson had inherited a considerable sum of money. This legacy enabled him not only to travel but also to relinquish his profession as a railway surveyor and dedicate himself to his natural history studies on a full-time basis. In 1848 he moved from Hampshire to Oatlands Park in Surrey where he commissioned the famous Newcastle architect, John Dobson, to build him an impressive mansion. He married Hanna Higgs on 3 June 1852, but sadly, she died in early 1854. There were no children from the marriage.

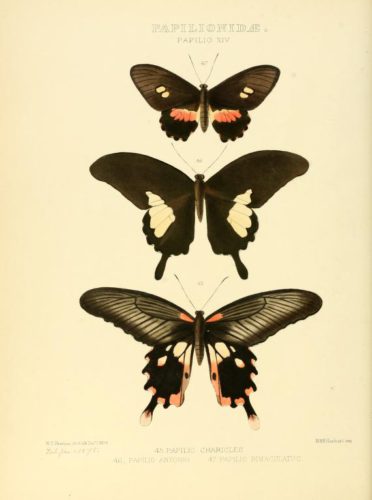

The passion for entomology that was a central component of Hewitson’s life resulted in him writing and illustrating a number of important works on this subject. These included his noted five-volume publication “Illustrations of New Species of Exotic Butterflies….” that appeared between 1856 – 1876. This included 300 coloured plates drawn by Hewitson that vividly demonstrate his considerable artistic talent.

Other works that Hewitson authored on the subject of lepidoptera include “Illustrations of Diurnal Lepidoptera”, “Equatorial Lepidoptera” and “Genera of Diurnal Lepidoptera”

William Chapman Hewitson died on 28 May 1878 at Oatlands, leaving no heir to his fortune. He made a bequest of £3000 to the Natural History Society of Northumbria and also bequeathed 166 books to the Society’s library. This is one of the most significant donations from an individual to the collection. Among the titles are some of the most treasured and important works in the NHSN library, including a first edition of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species….” and a copy of Edward Lear’s lavishly illustrated “Parrots”.

In total Hewitson bequested £51,200 to a range of bodies including the Newcastle Infirmary, this equates to over six million pounds in today’s prices. His estate at Oatlands was bequeathed to his closest friend, John Hancock, while the British Museum was left his butterfly collection, some pictures, and watercolours, in addition to his stuffed birds. He was buried at Walton-on-Thames.

I hope that you have found this blog as interesting to read as I found it to write. William Chapman Hewitson was a fascinating character who made a significant contribution to the study of the natural word and also proved to be an invaluable supporter of the Natural History Society of Northumbria and its library. All of the books that are mentioned in the blog are available to view at the Great North Museum: Hancock Library, which is free to use and open to everyone. At the moment the Library is temporarily closed because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Further information about the library can be found at https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives

I would like to thank the Archive of the Natural History Society of Northumbria for the use of their portrait of Hewitson, and the Biodiversity Heritage Library for the other images used in this blog.

As a charity, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums rely on donations to provide the amazing service that we do and our closure, whilst necessary, has significantly impacted our income. Please, if you are able, help us through this difficult period by donating by text today. Text TWAM 3 to give £3, TWAM 5 to give £5 or TWAM 10 to give £10 to 70085. Texts cost your donation plus one standard message rate. Thank you.