Imagine a deep ravine slicing across the Great North Road next to the Civic Centre, replacing concrete and tarmac with a beautiful tree-lined dean. Well, it’s not fantasy – this was Pandon Dean (or Dene – spelling varied). Much of the dean was still there well into the 19th century, and some of it survived into the 20th century. At its widest parts, the dean was as broad as Jesmond Dene, probably wider.

In present-day terms, the dean cut across the Great North Road from beside Claremont Buildings (on the left of the photo) to the gardens in front of the Civic Centre. It continued in a broad arc on the east side of Newcastle, down to the Tyne.

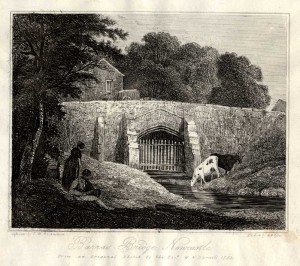

This little bridge – the original Barras Bridge – was Newcastle’s link with the main road to the north. The bridge crossed Pandon Burn low down in the dean. It’s shown here in 1788, shortly before it was rebuilt to a design by the Newcastle architect David Stephenson, in 1789. John Baillie described the changes in his An impartial history of the town and county of Newcastle upon Tyne of 1801:

This bridge, over a steep dean, was formerly narrow, ill built, and in dark nights dangerous to passengers, especially on horseback. Of late it has been widened about double its former extent, with a flagged foot way on each side, and is now made exceedingly convenient.

Once I heard that there is a still part of old Barras Bridge in Pandon [Burn] Sewer, about 3 metres below the present roadway, I was keen to see what it looked like. This is David Stephenson’s bridge, I believe, and I’m grateful to the City Library Local Studies staff who helped me obtain this photo from an old negative (City Engineer’s Photographic Section, Pandon Sewer 860/4, 1968, © Newcastle City Library). There was more work on the bridge in 1819, which seems to have taken the form of burying the bridge under a raised and widened roadway, and culverting the stream (in the comparatively small arch shown at the bottom of the photo) at the same time. The wall under the bridge arch in the photo would have been part of this later work. By the time of John Wood’s 1827 map and Thomas Oliver’s slightly later map (shown further down this blog), there’s no visible evidence of a bridge left, just a wide roadway.

Once I heard that there is a still part of old Barras Bridge in Pandon [Burn] Sewer, about 3 metres below the present roadway, I was keen to see what it looked like. This is David Stephenson’s bridge, I believe, and I’m grateful to the City Library Local Studies staff who helped me obtain this photo from an old negative (City Engineer’s Photographic Section, Pandon Sewer 860/4, 1968, © Newcastle City Library). There was more work on the bridge in 1819, which seems to have taken the form of burying the bridge under a raised and widened roadway, and culverting the stream (in the comparatively small arch shown at the bottom of the photo) at the same time. The wall under the bridge arch in the photo would have been part of this later work. By the time of John Wood’s 1827 map and Thomas Oliver’s slightly later map (shown further down this blog), there’s no visible evidence of a bridge left, just a wide roadway.

Path of Pandon Dean. The Civic Centre is on the left.. St Thomas’s Church is out of shot on the right

From Barras Bridge, Pandon Dean cut across the ground in between the present sites of the Civic Centre and St Thomas’s Church. The dean then curved to the left of the view in the photo, continuing eastwards towards what’s now the University of Northumbria and the motorway beyond. (John Dobson Street is in the distance, marked by a bus in the background of the picture.)

John Dobson Street, looking north to the Civic Centre.

Having walked through the Civic Centre gardens, we’ve moved into John Dobson Street, south of the Civic Centre. Pandon Dean was starting to broaden out here. A path led from the end of Vine Lane (near side of white building on the left) down into the dean. The path can be seen on this section of a map of 1833 by Thomas Oliver (John Dobson Street didn’t exist at the time).

Detail from Thomas Oliver’s map of Newcastle, 1833

John Baillie described walking from Vine Lane into Pandon Dean in his An impartial history of 1801:

…there is a handsome lane called Vine lane … passing down into what is called the Dean or Pandon dean, we … have … a small stream, with a pleasant walk; for this long winding hollow piece of ground, which was waste and wild, covered with brambles and thorns, is now totally converted, by the hand of industry, into a vast number of pleasant though small gardens, for the recreation of many of the industrious tradesmen of Newcastle.

This part of the dean was still there 90 years after John Baillie wrote his account. If we had walked down the path from Vine Lane into Pandon Dean, and then turned around to look back, this is the view we would have seen. This reproduction (apologies for the 1890s repro quality) of a picture by Robert Jobling was used to illustrate an article by R.J. Charleton in The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend in 1890 (Newcastle City Library Local Studies). Charleton wrote:

This part of the dean was still there 90 years after John Baillie wrote his account. If we had walked down the path from Vine Lane into Pandon Dean, and then turned around to look back, this is the view we would have seen. This reproduction (apologies for the 1890s repro quality) of a picture by Robert Jobling was used to illustrate an article by R.J. Charleton in The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend in 1890 (Newcastle City Library Local Studies). Charleton wrote:

Mr. Jobling’s view … shows some of the old gardens in front of Lovaine Crescent, with the little houses in which many of the occupants lived, the mill house [of the Oatmeal Mill] in the middle distance, and St. Thomas’s Church behind.

The oatmeal mill-house is on the right of the view. We can see a fenced-off oval in the centre of the scene where the stream cut down into the dean, while the path curved down the bank. This bigger section from Thomas Oliver’s map shows how the dean extended from Barras Bridge down to the Tyne, though the part closest to the river had been covered over by that time.

Detail of Thomas Oliver’s map of 1833, showing Pandon Dean from Barras Bridge to Pandon Gate in the town wall near the Tyne

The Newcastle historian Henry Bourne, in his History of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1736), enthused about walking up the dean from Pandon Gate, which was near the Quayside:

After you are out of Pandon gate there is one [passage] on the left Hand leading to Pandon Dean, a very Romantick Place full of Hills and Vales, through which runs Pandon Burn. It is a very entertaining Walk in the Summer to Magdalen Well.

Pandon Gate was an old gateway in the town wall. It’s shown on Thomas Oliver’s map a little way to the right of All Saints’ Church, which is at the bottom left of the map. Magdalen Well isn’t visible on the map, but it was located towards the top of the dean on this map detail. R.G. Charleton mentioned that the stream from Magdalen Well joined Pandon Burn in the dean approximately opposite the end of Vine Lane.

On the map, we can also see outlines of some of the gardens that lined the banks of the dean, making it such a pleasant place. As well as being attractive, the dean was huge – at its broadest parts, Pandon Dean was about 42 metres wide.

The long valley illustrated on Thomas Oliver’s map was the main part of Pandon Dean, where people walked and enjoyed the views. A little watercolour in the Laing collection, pictured above, shows what a lovely rural appearance the dean had. However, the stream and dean actually began further west – another blog looks at Thomas Miles Richardson’s Young Anglers, Barras Bridge, showing a scene in the dean west of Barras Bridge.

The long valley illustrated on Thomas Oliver’s map was the main part of Pandon Dean, where people walked and enjoyed the views. A little watercolour in the Laing collection, pictured above, shows what a lovely rural appearance the dean had. However, the stream and dean actually began further west – another blog looks at Thomas Miles Richardson’s Young Anglers, Barras Bridge, showing a scene in the dean west of Barras Bridge.

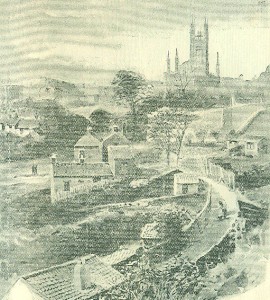

At this point, we’ve travelled about half-way down the main part of Pandon Dean. This view, of The New Bridge Pandon Dean 1821, was published in Eneas Mackenzie’s Historical Account of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1827). It was engraved by John Knox from a painting by John Lumsden. According to The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore And Legend, which published a sketchier version in 1890, this scene was:

At this point, we’ve travelled about half-way down the main part of Pandon Dean. This view, of The New Bridge Pandon Dean 1821, was published in Eneas Mackenzie’s Historical Account of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1827). It was engraved by John Knox from a painting by John Lumsden. According to The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore And Legend, which published a sketchier version in 1890, this scene was:

taken from near the foot of the steps which used to lead down from Shieldfield at the end of the lane called “the Garden Tops.” It was painted by John Lumsden in 1821, and shows the old water corn mill, afterwards the Pear Tree Inn, the town in the middle distance, and the Windmill Hills at Gateshead beyond.

This painting is so similar to John Lumsden’s view in the print that it’s probably also his work. John Lumsden (1785-1862) was a landscape, portrait and animal painter of St John’s Lane in Newcastle.

This painting is so similar to John Lumsden’s view in the print that it’s probably also his work. John Lumsden (1785-1862) was a landscape, portrait and animal painter of St John’s Lane in Newcastle.

The view is dominated by the New Bridge of 1812. All Saints’ Church is in the centre of the scene, behind the bridge. St Nicholas’ Church (now Cathedral) is on the right of the picture. Windmill Hills in Gateshead are in the distance, topped by several windmills. The River Tyne is not visible in this painting as it’s hidden in the valley between Newcastle and Gateshead.

I thought I would see if I could get a snap of a modern view of the scene in the painting, and this is what it looks like now – it’s the A167 Central Motorway East. The modern New Bridge Street raised roundabout (almost hidden by the far foot-bridge in the photo) crosses the road at roughly the same place as the New Bridge crossed the dean. All Saints’ Church is visible on the left.

I thought I would see if I could get a snap of a modern view of the scene in the painting, and this is what it looks like now – it’s the A167 Central Motorway East. The modern New Bridge Street raised roundabout (almost hidden by the far foot-bridge in the photo) crosses the road at roughly the same place as the New Bridge crossed the dean. All Saints’ Church is visible on the left.

Zooming into the picture, we can see people strolling by the burn and enjoying the beauties of the dean. These were described in an old song, published in Newcastle in 1826, fairly soon after the New Bridge was completed:

Zooming into the picture, we can see people strolling by the burn and enjoying the beauties of the dean. These were described in an old song, published in Newcastle in 1826, fairly soon after the New Bridge was completed:

The shrubs and flowers, sae fresh and green… the burn That wimples through the bonny Dean.

The New Bridge was built where the dean narrowed again. The depth of the dean in this area was about 70 feet (roughly 21.5 metres). This was the height of the Pandon Dean Embankment, built for the Newcastle and North Shields Railway in the 1830s, a little way south of the New Bridge (recorded by The Railway Times in 1839).

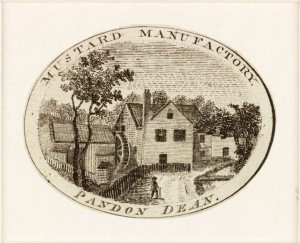

Looking through the left arch of the bridge in the painting, we can see yet another mill – the mustard mill.

The New Bridge marked the beginning of a period of change for Pandon Dean and the area further east. The bridge was built by the Newcastle master mason John Reed. In a footnote in his Historical Account, written at the time of Reed’s death in 1820, Eneas Mackenzie noted:

The New Bridge marked the beginning of a period of change for Pandon Dean and the area further east. The bridge was built by the Newcastle master mason John Reed. In a footnote in his Historical Account, written at the time of Reed’s death in 1820, Eneas Mackenzie noted:

Mr. Reed … was the only regular-bred master-mason in Newcastle in his time. [He suffered financial difficulties after building the bridge] … in consequence of the trustees being unable to pay for the work. A great part of the expense of the building still remains due; but the interest is regularly paid.

The cost of the bridge was £7448, 12 shillings and 10 pence, and building was started in 1811 and was completed in 1812, according to Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary of England, 1831. People had to pay tolls to use it, and it joined with the Newcastle to North Shields Turnpike road. It led to increased development in the Shieldfield and Byker areas.

On the right of the painting, we can see Newcastle’s ancient architectural heritage in the form of the castle, St Nicholas Church, and the town-wall fortification of Plummer Tower. This is the cylindrical tower with its blue-slate pointed roof at the end of the New Bridge, on the right of the picture.

On the right of the painting, we can see Newcastle’s ancient architectural heritage in the form of the castle, St Nicholas Church, and the town-wall fortification of Plummer Tower. This is the cylindrical tower with its blue-slate pointed roof at the end of the New Bridge, on the right of the picture.

Plummer Tower was built in the late-13thcentury and is still standing in Croft Street, off Market Street, fairly close to the Laing Art Gallery (the rectangular building on the right was added a lot later). The dean was a natural defensive barrier, and the town wall was built on its upper edge on the east side of town (the wall took in a short stretch of the dean that originally existed close to the Tyne).

Plummer Tower was built in the late-13thcentury and is still standing in Croft Street, off Market Street, fairly close to the Laing Art Gallery (the rectangular building on the right was added a lot later). The dean was a natural defensive barrier, and the town wall was built on its upper edge on the east side of town (the wall took in a short stretch of the dean that originally existed close to the Tyne).

The New Bridge lasted just over 50 years. It was removed in 1865 due to the filling up of the dean – its demolition was recorded in the Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales of 1870-72. The trains of the Blyth & Tyne Railway occupied this part of Pandon Dean in the second half of the 19th century, and The Monthly Chronicle commented that the ‘shriek of railway whistles’ had replaced ‘the sweet songs of birds’.

This is a section of a map produced in 1887 (the red line shows the most direct route from Central Station to Exhibition Park). The Blyth & Tyne Railway’s New Bridge Terminus was just north of where the New Bridge had stood. On this map detail, we can also see the area of Pandon Dean that still remained below Lovaine Crescent – it’s this area that Robert Jobling drew for the picture illustrated in The Monthly Chronicle (reproduced towards the beginning of this blog). Streets and railway lines have replaced most of the dean, however.

This is a section of a map produced in 1887 (the red line shows the most direct route from Central Station to Exhibition Park). The Blyth & Tyne Railway’s New Bridge Terminus was just north of where the New Bridge had stood. On this map detail, we can also see the area of Pandon Dean that still remained below Lovaine Crescent – it’s this area that Robert Jobling drew for the picture illustrated in The Monthly Chronicle (reproduced towards the beginning of this blog). Streets and railway lines have replaced most of the dean, however.

There is a fascinating later map – Thomas Oliver’s 1830 map overlaid with the outlines of streets and buildings of 1909 – which shows that small parts of Pandon Dean remained even in the early 20th century, including the gardens of Lovaine Place, near the present Civic Centre (Oliver’s plan of Newcastle, 1830, modified 1909, Tomorrow’s-history website – this map can be zoomed to see details.)

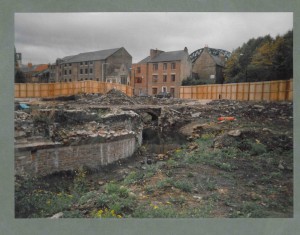

A photograph of Pandon Dean, taken prior to the building of the motorway and the New Bridge Street flyover, shows the remains of the dean’s railway use (the railway lines either side of the New Bridge area had been joined in 1909.)

This photo was taken by Newcastle photographer Jimmy Forsyth, and records excavations of Pandon Burn in the 1990s in the Stockbridge and Broad Chare areas. The Tyne Bridge is visible in the background. The dean skirted the east side of the mound on which All Saints’ Church stands, which is just out of shot on high ground to the right. (Jimmy Forsyth’s negatives are now held by Tyne & Wear Archives.)

This photo was taken by Newcastle photographer Jimmy Forsyth, and records excavations of Pandon Burn in the 1990s in the Stockbridge and Broad Chare areas. The Tyne Bridge is visible in the background. The dean skirted the east side of the mound on which All Saints’ Church stands, which is just out of shot on high ground to the right. (Jimmy Forsyth’s negatives are now held by Tyne & Wear Archives.)

Pandon Dean near the Quayside had been filled in at a very early date, and the burn channelled in a pipe. Pandon Burn originally entered the Tyne between Broad Chare and Love Lane. Part of Pandon Bank can still be seen at the end of Broad Chare(now widened). You can see it just below the street marked New Pandon roughly in the centre of the map section below, which is again from Thomas Oliver’s map of 1833 An illustration of Pandon Gate in the town wall as it looked in the early 19th century can be seen here, in an illustration in Newcastle Libraries Flickr stream.

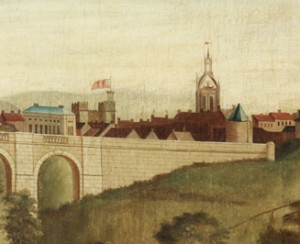

Detail of ‘Newcastle upon Tyne in the Reign of Queen Elizabeth’, 1852 by John Storey (1828-1888). Given by the Port of Tyne Authority, 1998

John Storey painted this scene of Newcastle in 1852, carefully reconstructing its appearance as it would have been 300 years earlier from evidence known in Victorian times. It shows Pandon Dean on the right of the scene, with All Saints’ Church on higher ground to the left of the dean. The painting gives us a good idea of how Newcastle was built on a series of hills with deans between them.

In 1890, R.J. Charleton wrote sadly of Pandon Dean in The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend:

To write of Pandon Dene is like writing of some departed friend. There is a tender melancholy associated with the place … And when we think of it as it once was gay with foliage and blossom and look upon its condition of to-day, buried far beneath a mass of ever accumulating rubbish, our melancholy is not unmingled with regret…

Well, this has been quite a long tour through Pandon Dean. This blog started out as a look at the Laing’s painting of the New Bridge over Pandon Dean. However, the dean was so huge and so startlingly close to the city centre of today that it seemed a pity not to start where the main part of Pandon Dean began, at Barras Bridge. If the dean had not existed, there would not have been a conveniently blank area available for building a 19th-century railway. When that was obsolete, motorway took over part of the dean’s site. It’s intriguing to think that as a result of that development, Pandon Dean, formed by the scouring of ice in ancient times, still shapes part of the city today.

52 Responses to The real Barras Bridge and Newcastle’s beautiful lost dean