The impetus for this post was provided by a chance meeting at Tyne Rowing Club. Phil Kite, one of the club members, was explaining the thinking behind his plan for a Tyne crew to take on the Talisker Atlantic Challenge in 2018. Phil told me that he wanted Team Tyne Innovation to demonstrate that the pioneering spirit of the North East is still very much alive by incorporating innovative products and services developed by regional businesses and universities. (1)

For my part, I couldn’t resist telling Phil how, in the 19th century, Tyne boatbuilders and oarsmen were also innovators, and were a major influence on the development of the racing shell. Sadly, very few people today are aware of the importance of the North East region’s contribution to the sport of rowing. The Tyne and Wear Archives & Museums Collections contain an interesting group of objects that illustrate that story, so what better time to bring these to the attention of a wider audience through a blog post. Thus, the innovators of today can be seen as the inheritors of a tradition stretching back almost two hundred years.

It all turned out to be a rather longer tale than even I expected so it has been split into two parts. Part 1 covers the outrigger, the bringing inboard of the keel, single strake (shell) construction, and the refinement of foot steering for coxless pairs and fours. Part 2 will deal with the development of the sliding stroke, the sliding seat and what seems to me might be the first bowloader coxed boat.

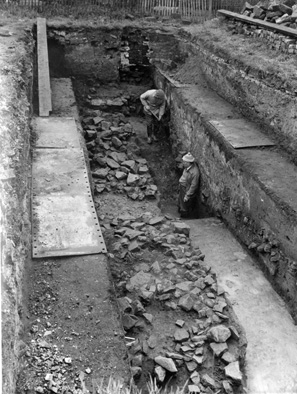

This race took place in September 1864 in very rough conditions. At the first attempt, on September 5th, Chambers’ boat was holed and the race was stopped when his scull began to sink. The race was rowed again the next day and this time Bob Chambers won.

TWCMS : G1197 (Shipley Art Gallery)

As Britain awaited the coronation of George IV, the leading citizens of Tyneside were casting around for a fitting way to mark the occasion. They agreed to promote a boat race on the River Tyne between the watermen of the settlements along its banks. The race would take place on Coronation Day, 19th July 1821, with cash prizes being awarded to the first four crews home: the brethren of Trinity House offered an extra prize of a blue silk flag for the winner.

Thirteen boats were entered but, when the day came, there was no race. Twelve of the crews refused to take part because the North Shields boat, the Experiment, had been built specially for the race, whereas the rest were work boats, used daily on the river. The Coronation Committee awarded the first prize to the Experiment, while Trinity House decided that the race was null. A new date, 1st August, the anniversary of the Battle of the Nile, was fixed for a contest for the boats that had been entered, except for the Experiment. Six boats started the rearranged race, with the Stella boat, the Laurel Leaf, winning the blue flag, and the first three boats home picking up the three cash prizes which had not been awarded on Coronation Day. (2) At the time the Laurel Leaf was regarded as a very fast boat, but her dimensions: length a little over 30 feet, breadth 6 feet, and height 30 inches, show how far things needed to progress before the racing boats for which the Tyne became famous would appear. (3)

Thus began the history of official boat racing on the River Tyne. Innovation in boat design and argument accompanied the first race: a pattern that was to be repeated over the following fifty years. Those years would create a golden age of rowing on the Tyne. At the start the men of the Tyne were striving to be able to compete against the best – the Thames watermen. But by 1870, greatly assisted by improvements in boat design and construction pioneered and developed by the boat builders of their native river, they were recognised as being the best in the world.

The 1821 North Shields boat the Experiment was clearly different from its contemporary foy boats, cobles and gigs from other localities along the river, but how it differed we do not know. However, the Tyne soon became the scene of many of the changes in design, construction and even rowing technique which led to the transformation of the work boat into the racing shell.

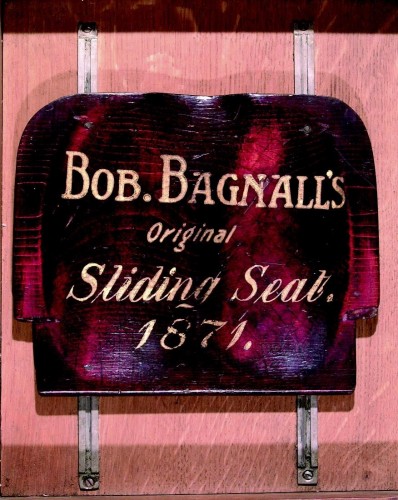

It is rare in life that somebody invents something that is both completely new and a perfect embodiment of their pioneering thought. Inventions are most often the practical application of an idea which may have been imperfectly executed by somebody else. This seems to be particularly true of boat design. It is not easy to pinpoint who first thought of a particular design change, but the Tyne has strong claims to the successful development of the outrigger, the bringing inboard of the keel, single strake (shell) construction and the refinement of foot steering for coxless pairs and fours. Despite a common local misapprehension, the sliding seat was not invented on Tyneside. But the sliding stroke had its origins on the northern river, which perhaps confused the issue, and a version of the successful American pattern of sliding seat had its victorious European debut in an important race on the Tyne. There is at least a moral claim of a Tyne component in the development and swift adoption of the sliding seat by the rowing world and so I have dealt with it here, without any intention of claiming the sliding seat itself as a Tyne innovation.

Finally, I will explore how and why the Tyne Champion four adapted their coxless four craft to take part in a coxed four race for professionals at the 1872 Tyne Regatta to produce what seems to have been the first bowloader coxed boat.

The Outrigger

The outrigger made its first appearance on the Tyne in 1828, fitted to a sculling boat, Diamond, for a race against Fly of Scotswood. A local boat builder by the name of Ridley built the wooden structure to the design of Anthony Brown of Ouseburn. In the same year Frank Emmet of Dent’s Hole on the Tyne produced a similar design. Two years later his Eagle made use of iron outriggers. Further attempts were made to develop the idea since a successful outrigger would enable racing boats to be made narrower and consequently lighter. Boats rowed on the gunwhale required sufficient beam (width) to enable an oarsman to apply adequate leverage to his oar. The fitting of outriggers altered the relationship between beam and leverage.

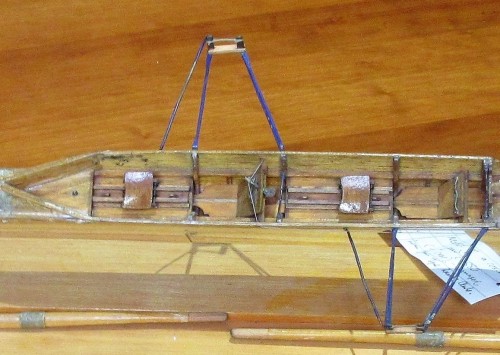

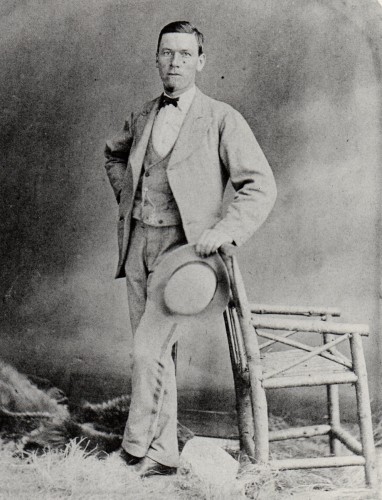

Outrigger on a model of a racing four by Matthew Taylor, Newcastle 1855

TWCMS : 1999.215 Scale: 1:12 (Discovery Museum)

In the early 1840s Harry Clasper and his brothers were racing in St Agnes, a four- oared boat, fitted with outriggers, which had been built by John Dobson of Hillgate, Gateshead. The Claspers became so successful in their races against other Tyne crews that Harry Clasper was convinced that they could take on the best of the Thames watermen.

A challenge was sent to London and the Thames men came north, encouraged to make the journey by the payment of expenses. The race was rowed over a five mile course from the 1781 Tyne Bridge to Lemington on 16th July 1842 for a stake of £150 a side. The Thames men were rowing on the gunwhale which meant that their boat was beamier than the St Agnes. But their boat was also considerably lighter; so much so that local opinion held that the London craft would prove too flimsy for the job in hand. The result of the race was an embarrassment for the Tyne crew with the Londoners winning easily.

Harry Clasper’s view of the loss was succinctly put in a letter to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle many years later in 1866.

“…… For I can prove that the outriggers were no use till I made the boats to suit them, nor was our old boat the St Agnes, for she was beat easy when we pulled the London boat on the Tyne;”

(Newcastle Daily Chronicle 22nd June 1866)

Despite the advantage of a considerably narrower hull, (29 inches as against 40 inches) the St Agnes was much more heavily-built than her London rival, weighing in at an estimated 224 lbs, fully 60% more than the Thames craft.

Harry had already starting building a new four-oared boat, The Five Brothers, with the help of finance from his wife, Susannah. Susannah came from the wealthy ironworks-owning Hawks family, but presumably also believed that her husband’s new boat was worthy of investment.

The appearance of The Five Brothers at the Thames Regatta in June 1844 was probably the moment when the outrigger reached a stage of development such that the rowing community recognised that this would be the future. The boat’s looks were the object of much admiration, with the five strake mahogany hull being French polished rather than being given the usual treatment of black lead (powdered graphite) and grease. At 168 lbs she was still heavier than the very finely built London boats, but now only by about 20%. The Claspers won the £50 prize and got very close to carrying off the £100 prize awarded to the winners of the top fours race. (4)

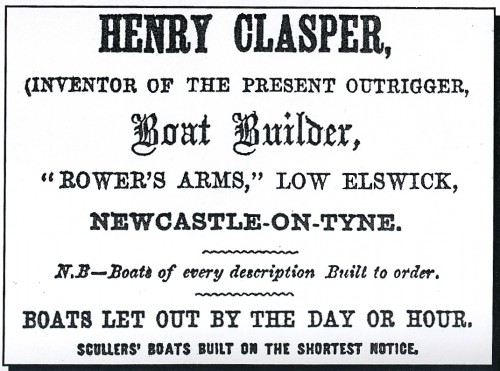

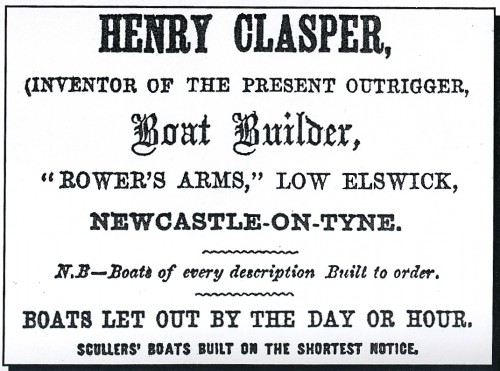

Advertisement from a Newcastle Trade Directory c 1861

Harry Clasper had persevered with the outrigger and refined boat design to suit the innovation until all recognised that his boats were faster than those rowed on the gunwhale. Thereafter Harry always claimed in his advertising literature that he was “the inventor of the present outrigger”, which was his way of saying that he had taken a previously impractical device and developed it until it worked successfully.

The Inboard Keel

While Harry Clasper was refining the design of the narrow, outrigger hull to reduce its weight, there were already signs that the need to reduce surface resistance (skin friction) was beginning to be understood. Although The Five Brothers had been planked up with five mahogany strakes each side of an external keel, the French polishing of the hull shows that Harry was looking for as smooth a finish to the underwater surface of the boat as he could achieve. The obvious next step was to smooth the hull still further, by moving the keel inboard and planking with a single strake, but who was the first to make that step is a matter of some debate.

Smooth hull of a model of a racing four by Matthew Taylor, Newcastle 1855. TWCMS : 1999.215

It has been claimed that the Londoner, Bill Pocock, was the first to build a keel-less boat but it is more generally accepted that the first keel-less boat came from the Tyne. This is all well and good, until one looks further into it, to find that three highly regarded Tyne boat builders, Harry Clasper, Robert Jewitt, and Matthew Taylor all have claims to have built the first keel-less boat!

Harry Clasper

Harry Clasper was encouraged by the success he achieved with his light, narrow-hulled outrigger, The Five Brothers, but he certainly was not satisfied. He would remain active as a professional oarsman for many years and his interest in developing racing boat design helped both his rowing career and his boatbuilding business. For his sculling match with Coombes on the Tyne in December 1844 he built a skiff (single scull) with a smooth hull, which had only one strake each side of the inboard keel.

“He (Clasper) has built himself a beautiful mahogany skiff, a perfect model in form, almost a toy, more fit as an ornament for a parlour than a boat to row in.”

(Newcastle Weekly Journal 14th December 1844)

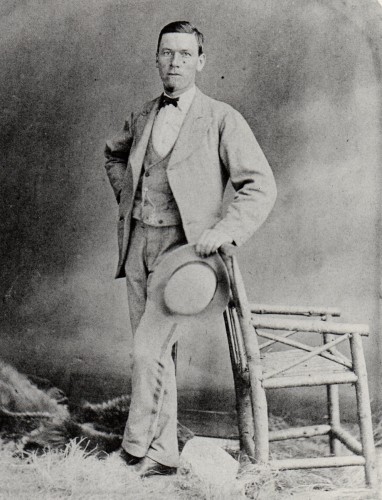

Harry Clasper, probably shown in the boat he built to race against Coombes in December 1844

The race took place on the 18th December but soon after the start Harry began to veer off towards the Newcastle bank because he was pulling too hard with his right- hand scull. After fouling a moored keel (lighter) on the northern side of the course, he found it difficult to get back on terms, and Coombes won comfortably by five or six lengths. A rematch was suggested for the following Monday, but in the event Coombes’ backers forfeited the £20 they had put down as the first instalment of the stake. In 1866 a newspaper review of Tyne oarsmen over the years, looking back at this contest, claimed that this was because Harry’s boat was better than Coombes’ old fashioned riggerless craft. Harry’s boat was still heavier than the Londoner’s, but only by a few pounds, and it may well be that despite his less polished technique Harry would have triumphed in the rematch, barring any further tangles with keels! Now the outrigger had been combined with lighter, one strake construction and an inboard keel, Harry’s boat was recognisably similar to today’s single sculls. (5)

Harry’s next four-oared boat, the Lord Ravensworth, was a further refinement and was also built with one strake a side. Using this boat the Claspers were victorious in the Thames Regatta of 1845, winning the top prize of £100. Harry’s boats in future would always be built this way, and over the next twenty years his boats were prominent at regattas all over the country. Many years later Harry’s son Jack (John Hawks) claimed in a letter that he steered a four to victory at the Thames Regatta of 1849 in which they, “used the same smooth-bottomed boats as are in use now”. (Dodd, The Story of World Rowing P75) If John Hawks Clasper remembered rightly then Harry Clasper’s claim to this change in construction is strong, since the other favourite, Matthew Taylor, did not bring the keel inboard until 1854. But that argument does not hold good in considering Robert Jewitt’s claim, since he declared he had built three boats with an inboard keel before December 1844.

Robert Jewitt

Robert Jewitt of Dunston on Tyne was an extremely popular builder of racing boats, with successful customers, both professional and amateur, on Thames and Tyne. He was particularly well known for the boats he built for James Renforth and his crews from 1868 to 1871, but he had established his reputation at a much earlier date. He was mentioned by the Newcastle Daily Chronicle as being worthy of special notice, together with Harry Clasper and Matthew Taylor, in 1859. The newspaper reported that,

“the Londoners seem to think that they (Jewitt and Taylor) have the only skiffs able to contend against Clasper,”

(Newcastle Daily Chronicle July 30th 1859)

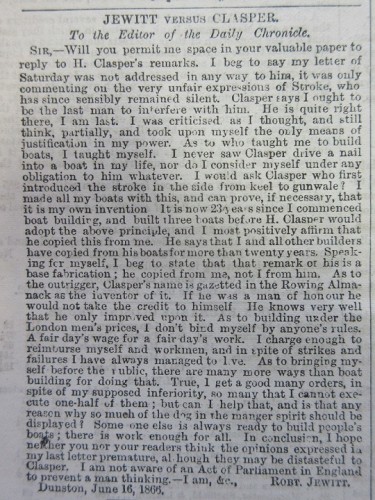

However, Jewitt was active as a boat builder well before 1859. An illuminating, but bad-tempered, exchange of letters with Harry Clasper in the columns of the Newcastle Daily Chronicle in June 1866 indicates that Jewitt began building boats in 1843.

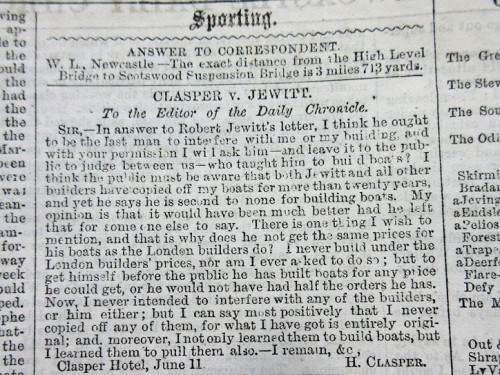

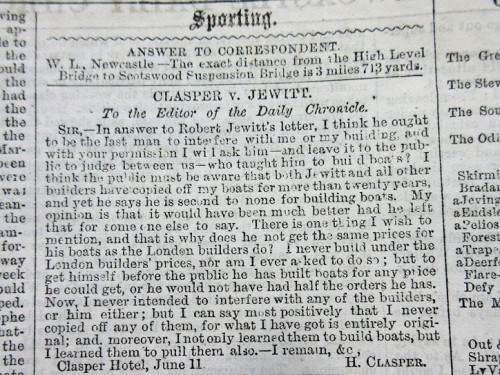

Jewitt had written a letter responding to a piece in the Chronicle by “STROKE”, and Clasper had taken Jewitt’s remarks to be a criticism of him (Clasper) and responded angrily, complaining that Jewitt and all other builders had copied from him. (6)

Clasper v Jewitt – Harry Clasper’s first letter to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle (12/06/1866) in response to Robert Jewitt

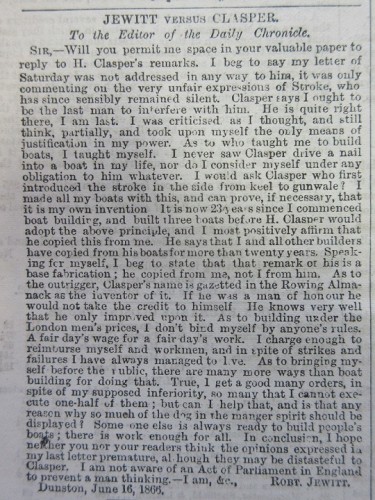

Unfortunately, I have been unable to find either STROKE’s piece or Jewitt’s first letter, to which Clasper took such exception. Jewitt replied, saying that he had been building boats for 23 years, and claimed that he had been the first to build boats with one strake from keel to gunwhale. He went on to say that he had built three boats on this principle before Clasper built his first, the single scull built for his race with Coombes on 18th December 1844. Jewitt also claimed that Clasper had copied the single strake idea from him. (7)

Clasper v Jewitt – Robert Jewitt’s letter to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle (18/06/1866) replying to Harry Clasper’s first letter.

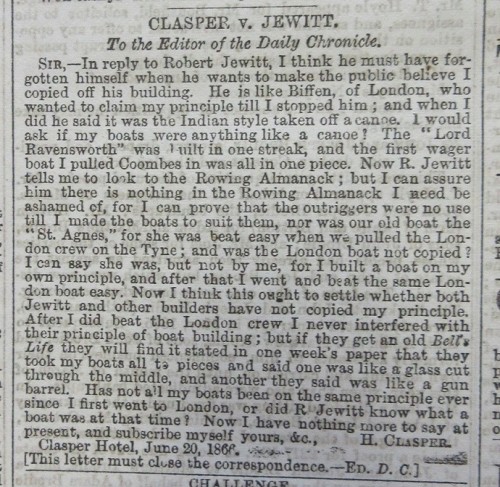

Clasper responded again, repeating his claims that Jewitt, along with others, had copied from him. However, in this second letter, the two boats Clasper references to back up his claim, the Lord Ravensworth, (1845) and the skiff he used to race against Coombes, (1844) were both built after the period when Jewitt claimed he had built three single strake boats. It is interesting that Clasper’s argument doesn’t refute Jewitt’s claim, but possibly his annoyance with Jewitt got in the way of delivering a more convincing response. (8)

Clasper v Jewitt – Harry Clasper has the last word, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, (22/06/1866) and the Editor closes the correspondence.

It is impossible to say who was right. The Editor of the Chronicle saw no future in continuing the argument and declared the correspondence closed after Clasper’s second letter was published. After the elapse of so much time the dispute can hardly be settled, but at the time nobody cast doubt on Jewitt’s claim that he was building boats in 1843. He could have built a boat on the single strake principle before Clasper built his boat to race Coombes in 1844, but the only evidence seems to be the claim he made in his letter of June 18th 1866.

Matthew Taylor

Inscription on the model of the Matthew Taylor four, dating it to March 12th 1855 together with his name and Newcastle location. TWCMS : 1999.215

Matthew (Matt) Taylor was a ship’s carpenter and a member of the well-known Taylor family of Tyne rowers. As well as pursuing a successful career as an oarsman and a coach, he also became a renowned boat builder. He built a smooth-bottomed four in 1854 in which the keel was brought inboard for the Royal Chester Rowing Club when he was working as the club’s trainer. In 1855 the club used the boat at Henley to win the Stewards’ Challenge Cup, and in 1856 Taylor built an inboard-keeled eight with which the club was again successful at Henley. This is really Taylor’s claim on the inboard keel: that he was the first to build an eight without an external keel. The principle seems to have been established in fours and sculls, perhaps by Harry Clasper, but possibly by Robert Jewitt, when Matt Taylor was only 15 or 16 years of age, and well before he gained a reputation for building boats with inboard keels.

Interior of Matthew Taylor model – showing the internal keel and also the footboard and the canted seat arrangement. TWCMS : 1999.215

Taylor’s most important contribution to the development of racing boat design was in his recognition that longer did not necessarily mean faster. His eights were 55 feet long, about ten feet shorter than the keeled eights of the time. They were also beamier than contemporary craft, but the great reduction in length resulted in a lighter boat with less surface in contact with the water and therefore with less skin friction. His boats were also shaped rather differently with the maximum beam being forward of the midships section.

Overhead view of Matthew Taylor model – The bow is at the right of the image and this view shows that the hull shape is rather fuller forward of amidships than it is aft. TWCMS : 1999.215

Matt Taylor was the most fashionable builder of his time, building boats for Oxford and Cambridge, sometimes, as in 1859, for both in the same year. In 1857, when both universities had agreed that only amateur coaches could be employed, Taylor was engaged by Oxford, who had commissioned him to build a boat for them. Obviously, they could not admit that he was coaching them and they needed to come up with a suitable reason for retaining his services. The Oxford President, Lonsdale, wrote of the arrangement,

“We employed him not to instruct us in the art of rowing, but to show us the proper way to send his boat along as quickly as possible.” (Dodd, The Story of World Rowing P73)

University Boat Race historians do not record whether or not Lonsdale went on to enjoy a career in politics!

Foot Steering

In July 1867, a crew made up of three fishermen and a lighthouse keeper from St. John, New Brunswick, in Canada, had caused a stir when they appeared at the Paris Regatta rowing a foot-steered coxless four. They won the amateur race against a background of concern, in Britain at least, as to whether or not they ought to have been classified as amateurs. The professional race was won by the Tyne Champion Four, which included James Taylor, a younger brother of Matt Taylor, the boatbuilder, from the famous rowing family of Ouseburn.

The St John crew’s boat was much heavier than a Tyne racing shell, but against amateurs the Canadians had put up an impressive performance. They rowed at a very high rating, used no foot straps and had no buttons on their oars. These features impressed the Tynesiders not at all, but foot steering was an idea that James Taylor saw would be worth developing further. In January 1869, when Taylor teamed up with the sculling champion James Renforth for a pairs race on the Tyne, he realised that adding foot-steering to their boat would greatly improve their chances of steering a true course up river.

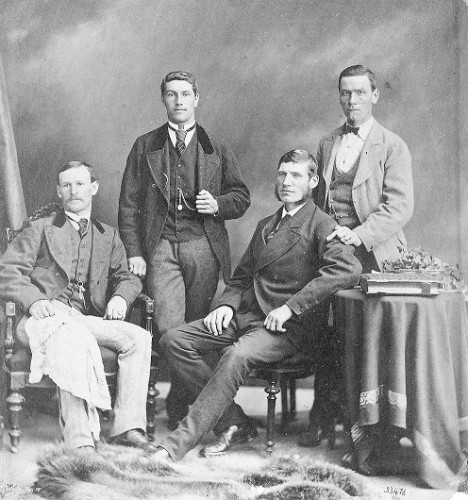

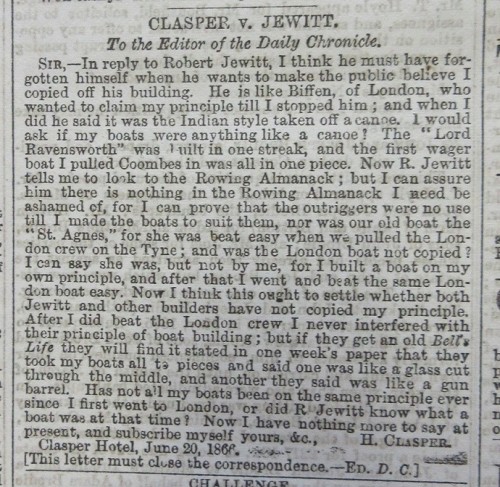

Photograph of James Taylor 1871 – James was a younger brother of the boatbuilder Matthew Taylor. His usual rowing weight was around 10 stone 7 pounds.

Renforth was a stone heavier than Taylor and an immensely powerful oarsman. Fitting foot-steering enabled Taylor to compensate for the imbalance of power between the two men without asking Renforth to ease his stroke.

“Taylor has adopted a rudder to the boat in which they row which he works by means of his feet, and he is thus enable to secure a certainty of steerage rare indeed in pair-oar races.”

Taylor and Renforth easily won the race, with near-perfect steering from the bow seat by Taylor adding to the margin of their victory. (9)

In England, fours races continued with coxes, largely because the London crews refused to dispense with them, but in 1870, when Renforth led a four to race against the St. John crew in Canada, the match was made in coxless fours. The correspondent of the Toronto Daily Globe saw this as an advantage to the Canadians since the Tyne men had no previous experience of racing in a coxless four.

The race was to take place at Lachine, near Montreal. While the Tyne crew were training on the course, James Taylor became dissatisfied with the design of the steering apparatus. He was steering with his feet from the bow seat, but felt that the working of the apparatus interfered with the free action of his feet. It is not made clear how exactly the feet were hampered, but it seems likely that the bow man’s ability to drive off the footboard was restricted. I would suggest that the controlling device was some sort of fore and aft pedal. The St. John crew rowed a fast, arm stroke so this was not significant for them, but the Tyne crews used their feet a great deal in executing their sliding stroke. The bow man probably had to restrict his leg drive in order to maintain a steady course.

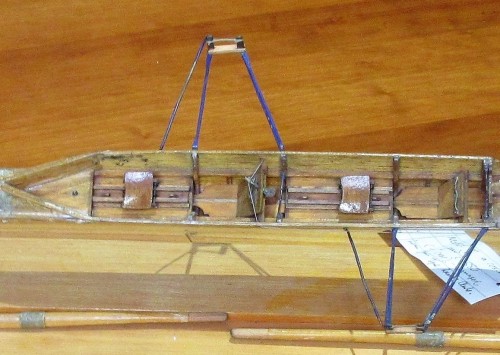

Model of a pair oar c1880 with foot steering fitted for use by the rower in the bow seat. This model has two footed steering controlled by a lever which sits between the feet. The long slides and seats running on wheels suggest that this model was made a few years later than the first appearance of sliding seats on the Tyne in 1871. Tyne Rowing Club. Scale 1:12

Taylor designed a semi-lunar lever, working freely on a pivot, that moved side to side across the footboard and therefore allowed him to drive his feet off the board without inadvertently altering course. Fortunately for the Tynesiders there was a large body of workers at the Canadian Grand Trunk Railway workshops who had been recruited from Northumberland and Durham. They were delighted to be of assistance and quickly manufactured the new apparatus to Taylor’s design. Renforth’s crew gained an easy victory over the Canadians, rowing with their usual, long, fluid stroke, but also able to benefit from accurate foot steering. (10) It seems to me that the Tyne Rowing Club pair oar model has this type of foot steering fitted to it.

A further refinement seems to have been made when two professional fours raced for the Championship of the Tyne on 22nd November 1871. Most of the details of this race can be found in the following section on the sliding seat, since this was the first outing for sliding seats on the Tyne. However, following the experience of both crews in racing without coxes in America earlier in the year, this race was also contested in coxless fours.

All the previous accounts of steering apparatus used in coxless boats referred to steering with the feet, plural. The account of the race published in the Chronicle the following day described something new.

“The steering apparatus is the invention of Mr. Thos. Swaddle, foreman to Mr. Jewett, and its novelty consists in the fixing and arrangement of the lever, which is worked with one foot only, whilst the other is strapped in the usual manner.”

(Newcastle Daily Chronicle Thursday 23rd November 1871)

This arrangement allowed the bow man to use the strapped foot to drive off the footboard exactly as he would have done before. This is much the same arrangement as in use in coxless boats today. Incidentally, this is the Thomas Swaddle who a few years later went into partnership with William Winship to build famous racing boats from their yard near the Scotswood Bridge.

In Part 2 I will explore how the sliding stroke on a fixed seat pioneered on the Tyne developed into a viable sliding seat in North America and also what seems to be a first, and successful, outing for a bowloading coxed four in 1872.

Part 1 – References

- See the team’s website, https://www.teamtyneinnovation.com/ and also the challenge they are taking on, https://www.taliskerwhiskyatlanticchallenge.com/

One of the innovative products Team Tyne are using on their boat is, Intersleek 1100SR Foul Release paint, developed and manufactured by International Paints (Akzo Nobel) at their plant in Felling. This paint already has a place in the Tyne & Wear Collections and was chosen in 2013 as one of 100 objects that tell the History of the North East. http://www.100objectsne.co.uk/objects/view/24

- Newcastle Daily Chronicle (NDC) Sept. 20th 1870

- NDC July 30th 1859

- NDC 15th February 1866

- Newcastle Weekly Journal (NWJ) 21st December 1844, NDC 15th February 1866

- NDC June 12th 1866

- NDC Monday June 18th 1866

- NDC Friday 22nd June 1866

- NDC 26th January 1869

- NDC September 28th 1870

Bibliography

Clasper, David, Harry Clasper Hero of the North, Gateshead, 1990

Clasper, David, Rowing: A way of life, The Claspers of Tyneside, Gateshead 2003

Dillon, Peter, The Tyne Oarsmen, Newcastle 1993

Dodd, Christopher, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, London, 1983.

Dodd, Christopher, The Story of World Rowing, London, 1992

Waters, Balch, The Annual Illustrated Catalogue and Oarsman’s Manual for 1871, Troy, New York, 1871

Whitehead, Ian, The Sporting Tyne, A history of professional rowing, Gateshead 2002

Whitehead, Ian, James Renforth of Gateshead, Champion Sculler of the World, Newcastle 2004