During my latest bimble along Hadrian’s Wall, I inevitably ended up at one of my favourite Roman sites, the Mithraic temple site at Carrawburgh. The Roman name of the nearby fort site was Brocolitia. This was probably based on the original Celtic name for the area and it’s possibly translated as “Badger Holes”. The temple isn’t dedicated to the god of badgers though- it was built to honour the god Mithras.

Mithras was a Persian god from the East, god of light and heavily associated with the sun. While we know that Mithras was worshipped as far back as 1400 BC, it wasn’t until the second century AD that Rome began to embrace the cult- Legion XV had returned from the East and began to spread the cult along the frontiers of the Danube. Mithraism inevitably reached the province of Britannia soon after.

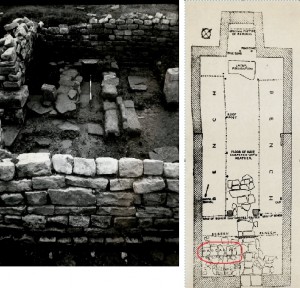

The site at Carrawburgh has been restored and preserved to its latest fourth century plan, complete with replicas of the altars that are in the Hadrian’s Wall gallery in the Great North Museum: Hancock, but it had experienced several stages of building and reconstruction before this phase in its history. While admiring a nicely preserved archaeology site or viewing the altars in the museum gallery, it’s easy to forget about the stories of the site that were uncovered during the excavation.

The Carrawburgh Mithraeum had been built in a swampy area to begin with and over the years the structure had become submerged by water and peat. Lost to time, the site was only discovered in 1949 when a severe drought dried out the swamp and shrunk the peat levels down to such an extent that the top of one of the altars began protruding out of the ground. A chap enjoying a walk in the area, who just happened to be a member of the Society of Antiquities, recognised the significance of the object and alerted the landowners. The following year, the land was drained and fully excavated by a team led by Ian Richmond and John Gillam from Durham University’s King’s College, which would later become the University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

So what did Richmond and Gillam find?

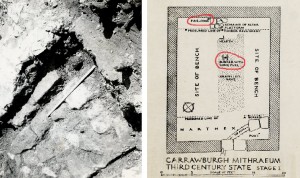

They discovered that the mithraeum in Carrawburgh had three distinct states. It began life in the early 3rd century, barely big enough to fit a dozen worshippers inside. Aswell as identifying such fundamental aspects of the temple such as where the entrance was located, one discovery in particular was interesting to me- pine cones. Near the back wall of the temple, close to the remains of the altar platform, a single Mediterranean pine cone was found.

While it’s always tempting for archaeologists to label unusual finds as “ritual deposits”, it turns out that this pine cone was indeed a ritual object. We know from texts on oxyrhynchus papyri discovered in Egypt that in the time of the Roman Empire, pine cones in Egypt were used in sacrifices, were given as presents among friends and were purchased in sets of 10 or 16. These pine cones would have been used to hallow the altar platform or ward off evil. The peat swamp also preserved the remains of a second pine cone that was heavily charred. On initial discovery, this appeared to be an odd find as pine cones are highly flammable and should have been consumed when used as fuel for a fire. On closer inspection however, it was shown that the cone had been carbonised to make it burn slowly and steadily. This would have given the cone a dark red glow as it burned, and emitted a pungent aroma. These finds of simple pine cones immediately gave us an impression of what the atmosphere and environment within a Mithraic temple may have been like.

At some time at around 222 AD, it’s thought the mithraeum went under a complete redevelopment, with the temple being enlarged and the interior reconstructed, presumably to accommodate more worshippers. Again, the excavations on this second stage of the mithraeum uncovered some intriguing developments. At some point the floor level was raised in the anteroom of the temple to accommodate the insertion of an oblong shaped stone receptacle into the ground, 18 inches deep. It looked to the excavators like a coffin, and after a willing volunteer from the team climbed into it and lay down to test it out, the “coffin” fitted perfectly.

This ordeal pit, as the area was known as, would have been a place for initiates into the cult to prove their mettle. It was close to the hearth, so no doubt the men could be subjected to ordeals involving heat and cold, a part of the Mithraic tests of endurance and terror induced by being entombed. The thought of this brings on a slight feeling of claustrophobia in this blogger, although it does give us yet another precious, if somewhat gruesome glimpse into the ways of Mithraism and what occurred in the secret confines of the temple.

It’s thought that the mithraeum fell into disuse at some point in the early 4th century. Some of the statuary appear to have been damaged deliberately, one theory being that a Christian commanding officer of the fort ordered the desecration. Water levels in the area rose, and by the middle of the century it seems as if the area was being used as a rubbish tip. And so the mysteries of the temple at Carrawburgh seemed lost to the ravages of time. The 1950 excavation at Carrawburgh has been celebrated however for revealing a host of details that can help deepen our understanding of this mysterious cult. The surviving altars and statuary now on display at the Great North Museum: Hancock provide immense amounts of information to scholars and researchers, but it’s easy to forget that for every object on display, the excavation that produced the object will have provided many more insights and theories into a way of life that we are still learning about today.

Thanks to Richmond and Gillam’s detailed excavation, a reconstruction of the mithraeum was built at the Museum of Antiquities. A film of the mithraeum can be today in the Great North Museum: Hancock.

4 Responses to Pine cones and coffins: looking back at Carrawburgh