Read Part 1 of What ever happened to Saltwell Park Museum?

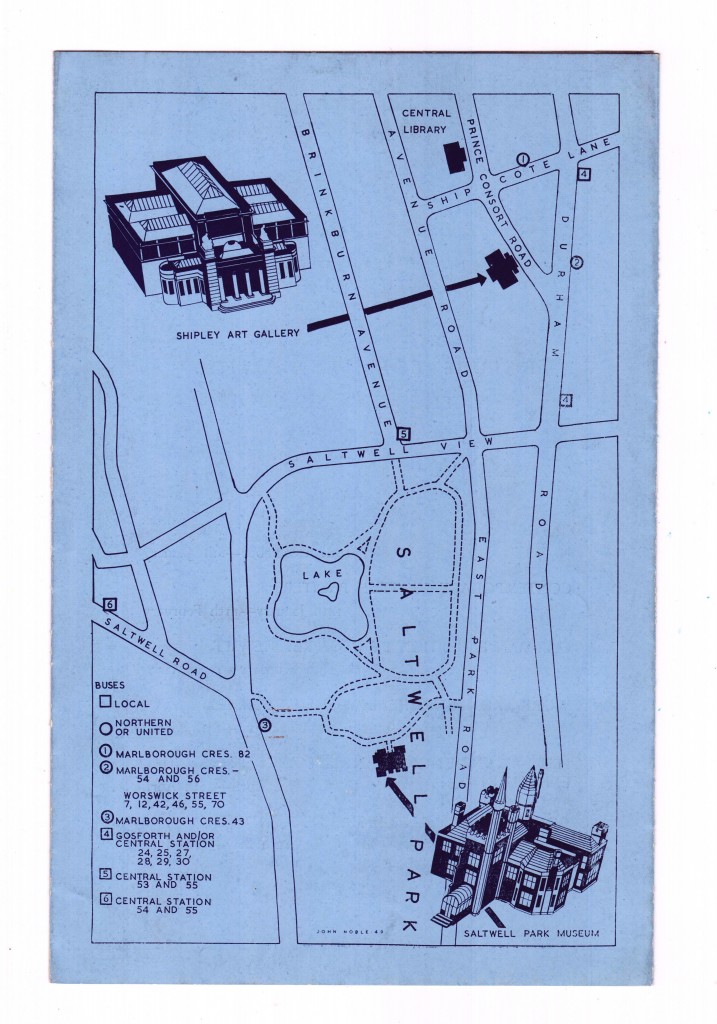

Saltwell Park Museum and Saltwell Towers have a close connection to another Gateshead building, the Shipley Art Gallery. Their stories are connected to another man who lived in the Towers and made a lot of money from the Industrial Revolution.

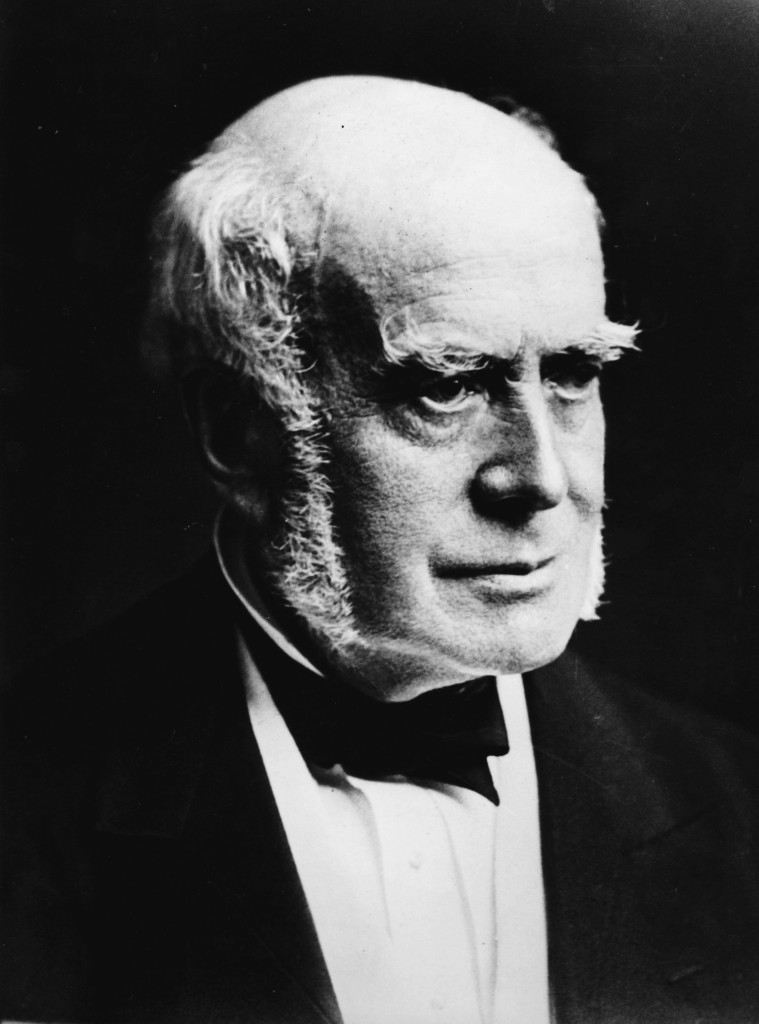

Joseph Ainsley Davidson Shipley was a Newcastle-based solicitor who moved in as the tenant of Saltwell Towers after William Wailes died in 1881. Joseph Shipley liked art and with his wealth built up a large collection of 16th and 17th century Dutch paintings. When he died in 1909 his collection was offered to the Gateshead Corporation. In 1917 the Shipley Art Gallery was opened, built by the Gateshead Corporation: it is still a public building today. The ‘Shipley Bequest’ of paintings formed the basis of its collection.

Joseph Ainsley Davidson Shipley, a wealthy solicitor who liked art and left his collection of 16th & 17th century Dutch and Flemish paintings to the Gateshead Corporation.

The Shipley Art Gallery was built during a period that would mark the beginning of the end of the British Empire and its global superiority. Near bankrupt by the First World War, the British Empire would continue to hang on to its dream of global domination for another half century, but in reality its peak of wealth, influence and power had waned and it was in decline. The next two decades following World War I would see a period of intense social and political upheaval and change. Mass unemployment caused by a severe global depression, another looming global conflict and an emergence of totalitarianism in Europe would all have a major impact on Tyneside and the people who lived there.

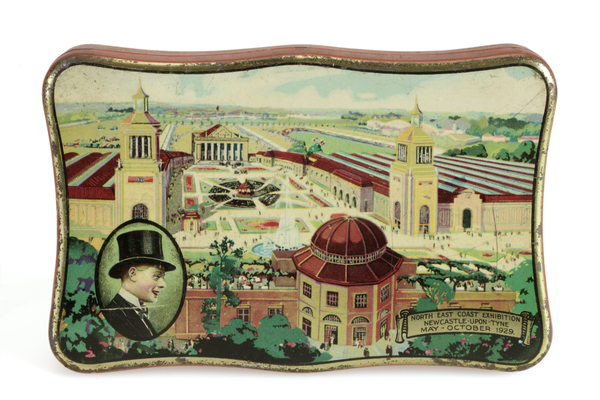

In 1929 the North East Coast Exhibition was held at Exhibition Park in Newcastle upon Tyne. Memorabilia made for the exhibition was steeped in nationalism, flag waving and the faces of the Royal Family on mugs.

Memorabilia from the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition showing Edward, Prince of Wales smoking a cigarette.

At one time Tyneside and the North East of England was called the ‘Workshop of the World’. Tyneside’s heritage has been largely created and constructed on the basis of its experience of the Industrial Revolution; its legacy is still, to this day, something that the region holds onto and there remains a lot of pride and promotion concerned with it.

The 1929 North East Coast Exhibition in Exhibition Park, Newcastle, would be the first time the region would present this as ‘History’ and proclaim its heritage and status to the world as a very considered and very political public relations exercise. It echoed the Jubilee Exhibition that was held on the same site in 1887, a time when the British Empire was at its peak. It is from the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition that the Newcastle Science Museum would be created, a museum which would later evolve into Newcastle’s Discovery Museum. It was the start of the ‘Heritage Industry’ in the North East. It’s not a coincidence that in 1933, possibly motivated by political and regional rivalry and in keeping with the prevailing zeitgeist, Gateshead Municipal Borough would open the ‘Gateshead Local & Industrial Museum’.

More memorabilia from the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition showing Edward, Prince of Wales in a top hat and an illustration of the park and buildings.

On a very basic level museums are generally assumed to be about preserving and looking after the history and heritage of a culture; this is something we’ve come to expect and maybe in some ways take for granted. Public or Civic museums are a relatively new thing if we consider they only started to emerge in the early 20th century and it’s interesting to trace their evolution and the conditions from which they came into being. Museums create and present a sense of place and try to tell a story about why things exist and what that means for people. They are about learning and knowledge and try to bring communities together around an idea.

Museums can function for many different reasons but in essence they are hugely political tools and the kind of stories being told and the way they are told depends on who is telling them and why. Museums are used to promote a sense of place but they also help provide one. If a town, city or metropolitan area doesn’t have a museum what does that mean?

Before 1933, Gateshead didn’t have a museum. It had an art gallery – a really good one with a collection of ‘Old Masters’ – but it didn’t have a museum. So in 1933 the Gateshead Parks Committee agreed to open a museum in Saltwell Towers, which it still owned.

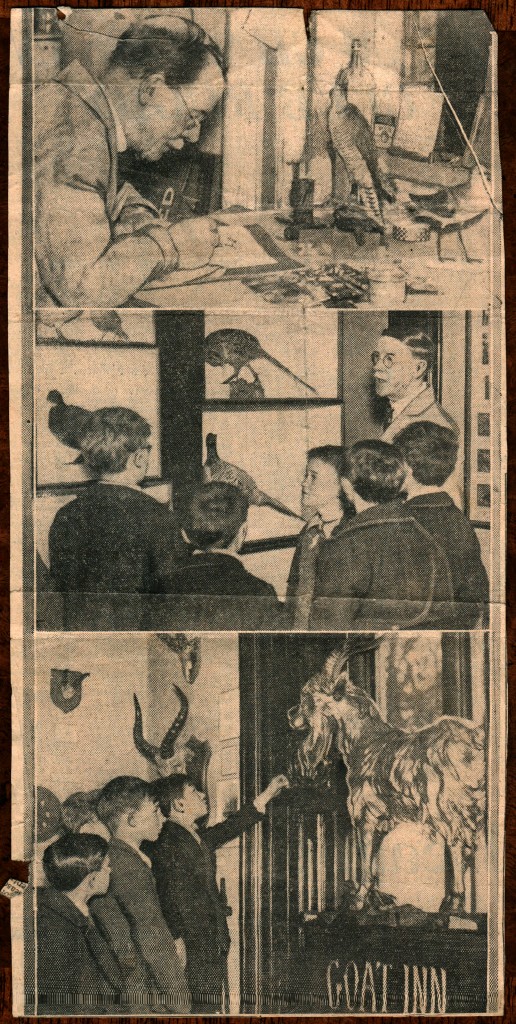

During World War I (1914–1918) Saltwell Towers had been used as a military convalescence hospital but from 1923 it had been empty and without a tenant. The curator of the Shipley Art Gallery at this time, Matthew Young, would be given responsibility of managing the new museum and the renovated building. An assistant curator/caretaker for the museum was employed. He was called Frank Young although he wasn’t related to Matthew. Frank would live in the museum in the park with his wife Bella up until his death in 1943. All the original object labels from when the museum opened were hand written by Frank and a lot of them have survived the intervening 80 years.

Photographs from inside Saltwell Park Museum from a 1930s edition of ‘North Mail’ newspaper showing Assistant Curator, Frank Young at work and some children looking at ‘The Golden Goat’.

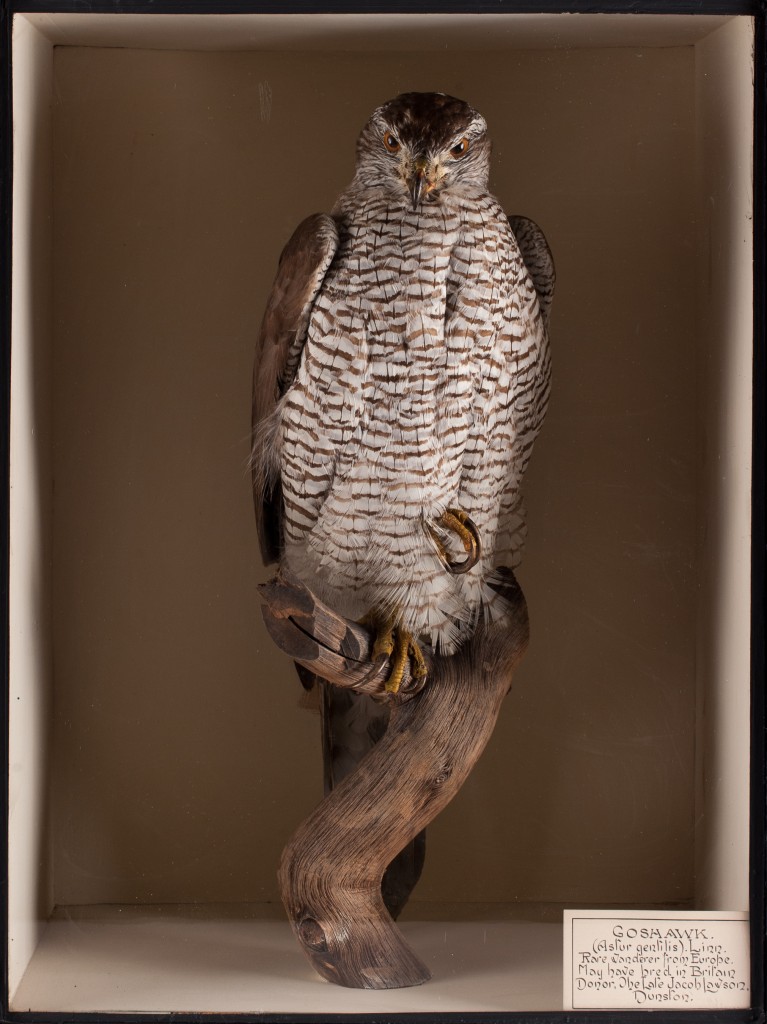

Before its opening the museum didn’t have a collection, it had to create one and it did this by getting people who lived in Gateshead to donate to it. Most of these people were from the middle class of Gateshead, people with money, means and influence within the borough. They contributed to the collection of ‘Historical’ objects and, whether consciously or not, promoted their ideas of what ‘History’ was and what that should mean for people. The museum also received donations from other museums, in particular the Hancock Museum in Newcastle, whose collection was made up primarily of ‘Natural History’. The ornithologist, taxidermist and landscape architect John Hancock, whose collection formed the basis of the Hancock museum, would stuff birds shot by the Liddell family. The Liddells were a rich family who lived in Ravensworth Castle near Gateshead. The Ravensworth collection of taxidermy would end up in Saltwell Park Museum.

A Goshawk. Taxidermy from Saltwell Park Museum. Many of these birds came from ‘The Ravensworth Collection’ of taxidermy. Photo Credit: Karolina Maciagowska

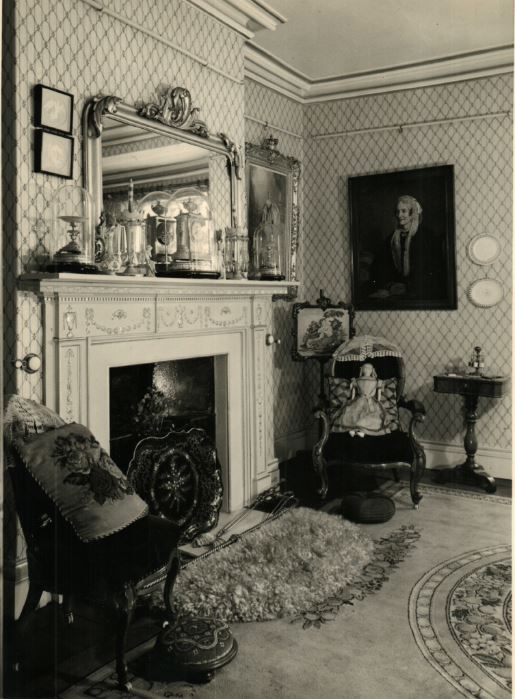

There are not many photographs from inside Saltwell Park Museum. But its collection and displays reflected a particular Victorian and Edwardian view of the world. It is a collection that concerned itself with the British Empire, Britain’s status in the world and pride in the ‘industrial activity’ within its locale. It had exotic ideas about other cultures and did not consider the ethics of its Natural History collection in the way we would today. It was a museum of its time and the view point was that of a patriarchal, white and mostly male-dominated society. As with other regional and ‘Local’ museums that opened in Britain in the first half of the 20th century, it was an attempt by a local council to replicate the kind of collections that rich aristocratic families would display in their large stately homes, displays of wealth and power.

The ‘Victorian Room’ at Saltwell Park Museum. Photograph from the 1950s.

The Museum was also the local council’s way of creating a sense of place for people, establishing a coherent historical narrative for the town and imbuing a sense of ‘civic pride’. They did this by displaying the products and evidence of a once thriving local industrial base: glass, pottery, ceramics, iron, coal, rope, cables, brick manufacture and ship building. An industrial base that was in deep decline.

Here is an excerpt from the ‘Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Newcastle upon Tyne’ published in 1933 and written by Walter H Young (no relation to either Frank or Matthew) about the new ‘Municipal Museum. Gateshead’:

“For some years past it has been felt that a Town’s Museum would be of interest and educational value; and to some of the more active minded citizens of the borough, it was obvious, that there stood, ready to hand, and in the most attractive of surroundings possible in an industrial town, a building which would only need renovating and modernising to be worthy to house, for some years to come, a representative series of exhibits showing the history and industrial activities of the district.”

One Response to What ever happened to Saltwell Park Museum? (Part 2)