A guest post by Lauren Haikney, a History student at Durham University.

The advent of the First World War was a defining event in the lives of civilians as well as those in the military. So-called ‘enemy aliens’, people who had settled in territories which were now at war with their homelands, have until recently been overlooked in the study of the war. North-East England was home to a thriving German community, with many of the immigrants having lived in the region since the mid-nineteenth century. German Evangelical churches had sprung up in South Shields and Sunderland, and German butcher’s shops were common; at the same time, many of them anglicised their names and became naturalised. However, with the war came frenzied anti-German sentiment whipped up by the press; the Germans’ commitment to integration would not count for much.

Months of well-publicised spy-scares and German military atrocities, culminating with the torpedoing of the Lusitania passenger liner in May 1915, sparked the outbreak of rioting across the country in that month. Violence in the North East was concentrated in Newcastle and South Shields, where on the night of the 15th May 1915, it was reported that 7,000 rioters assembled in the Market Place, destroying shops belonging to Germans and shouting, “Remember the Lusitania!”. But more personal issues were also at play. A young Gateshead labourer named Arthur Adams received news on 10th May that two friends had been killed at the front. His response was to enter the butcher’s shop owned by Charles Frederick Seitz, and to attack the startled German with a brick, forcing him to barricade himself in the back room.

TWCMS: 2001.4958 A photograph from the South Shields Museum & Art Gallery collection of Market Place in South Shields

Fortunately, it seems Arthur Adams was not representative of the North East as a whole. Many local people stood by their German neighbours in the face of the mob. On the night of the 15th May, the butcher’s shop owned by Frederick Seitz (a distant cousin of C.F. Seitz) came under attack. A twenty-year-old South Shields woman, Matilda Carney, was inside at the time. As a domestic servant of the Seitz family, she was caught between two loyalties. Yet Matilda decided to protect the German family, aiding the escape of Mrs. Seitz and her five young children, and sheltering them at her own house overnight. For some, the wartime rhetoric of the murderous German barbarian did not infiltrate their personal relationships with the real Germans who lived alongside them.

STH0004368 A photograph taken from South Tyneside Libraries collection (www.southtynesideimages.org.uk) of Fred Seitz & Sons’ Pork Butcher shop, which was situated at 11 Market Place

The war eventually saw the internment of most German men of military age (between 17 and 55), and widespread deportation. In this legislation, the government took its lead from the anti-German press, the mobs of 1915, and the increasingly reactionary feeling in parliament. But it is important to remember that the war did not turn all British people into violent anti-German rioters. Those who remained loyal to their long-standing German friends, neighbours and colleagues also deserve their place in the narrative of the German community during the First World War.

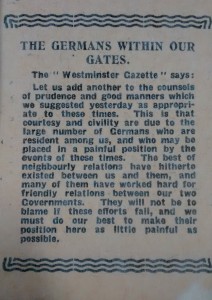

‘The Germans within our gates’ taken from the Illustrated Chronicle, on 6 August 1914 reproduced by the kind permission of Newcastle City Library

Lauren is currently writing her dissertation, ‘Germans and Geordies: The Great War and the German Minority of Newcastle and South Shields’. Her research has contributed to Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums’ new online exhibition, ‘The Kuch family on Tyneside: A story of changing attitudes towards German migrants in Britain.’ Click here to view it on Google Cultural Institute.

One Response to The changing attitude towards German migrants in Britain