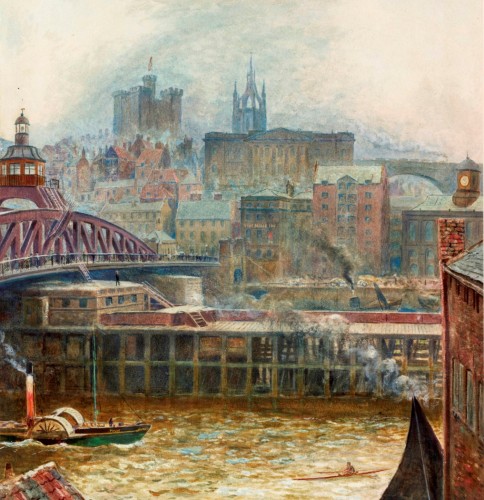

This magnificent panorama shows Newcastle in 1895, at the height of the city’s industrial development. Hundreds of ships left the Tyne every month for destinations in Britain, Europe and America. Newcastle dominated the British coal trade and its shipyards built some of the biggest ships in the world. Massive railway development spurred on the development of industry. As a result, in the 60 years from 1851 to 1911, the population of Newcastle more than tripled from 87,784 to 266,671.

This view was painted by Niels Møller Lund (1863-1916), an artist of Danish ancestry who grew up in Newcastle. Although he moved away as he established his artistic career, he continued to visit the North East on painting trips. His picture is part of the Northern Spirit displays at the Laing Art Gallery.

Lund has arranged his picture so that sunlight picks out a pair of grand sailing ships at the quayside.

Another huge sailing ship is being towed by a steam paddle tug through the open Swing Bridge. However, steam ships, like the black-painted vessel at the quay, were more typical of the shipping trade by the date of the picture.

Another huge sailing ship is being towed by a steam paddle tug through the open Swing Bridge. However, steam ships, like the black-painted vessel at the quay, were more typical of the shipping trade by the date of the picture.

In Lund’s painting, several steam trains are crossing the High Level Bridge, which had been opened by Queen Victoria 46 years earlier, in 1849. The new bridge was an immensely important land link between England and Scotland. It meant that road traffic could pass through Newcastle without having to negotiate the steep, narrow Side, as had been necessary for centuries.

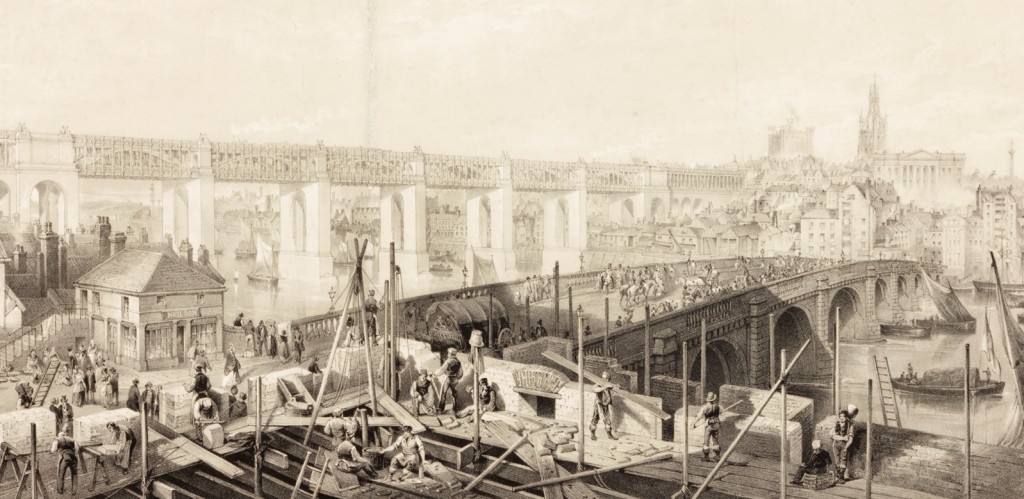

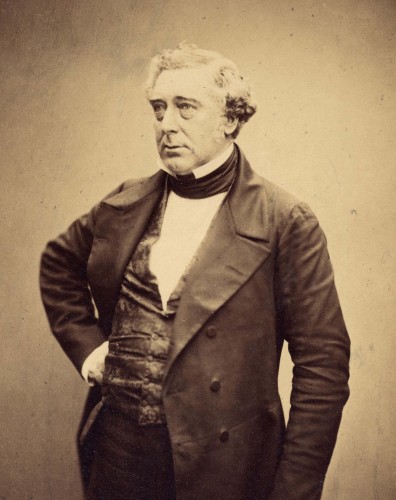

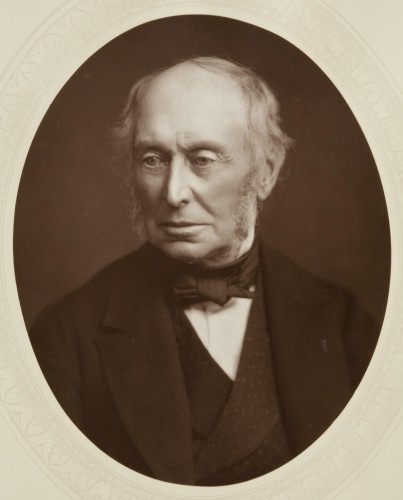

The bridge was designed by Robert Stephenson (pictured alongside) and Thomas Elliot Harrison. It was an astonishing engineering achievement, and its double-decked structure, with road below and rail above, was unique when it was built. The foundations were made from elm piles driven into the river bed by engineer James Nasmyth’s newly patented steam-driven pile driver. About 650 Newcastle families suffered the loss of their homes, knocked down to build the approach to the bridge.

The bridge was designed by Robert Stephenson (pictured alongside) and Thomas Elliot Harrison. It was an astonishing engineering achievement, and its double-decked structure, with road below and rail above, was unique when it was built. The foundations were made from elm piles driven into the river bed by engineer James Nasmyth’s newly patented steam-driven pile driver. About 650 Newcastle families suffered the loss of their homes, knocked down to build the approach to the bridge.

John Wilson Carmichael’s view shows the bridge being built in 1848 (he has imagined the removal of scaffolding), with a construction yard set up at the end of the old stone Tyne Bridge. Travellers had to pay tolls to cross the High Level Bridge. It was a penny for a pedestrian, three pence for a horse and wagon, and ten pence for twenty cattle.

It wasn’t until May 10th 1937 that the bridge became toll-free, after the bridge was purchased from the railway company by Newcastle and Gateshead Corporations. John Grantham, Mayor of Newcastle, is pictured at the ceremony on the bridge. The old Redheugh Bridge was purchased from the bridge company at the same time. The cost for both bridges was £275,060 (£112,530 contributed from central Government), with Newcastle paying the lion’s share as most of the width of the river lies within the city’s boundary. This was a very large sum at the time, but the benefits for trade and transport were thought to be worth it.

The old Tyne Bridge eventually became a hindrance to shipping because it was so low. After the old bridge was knocked down, there was a temporary wooden bridge, which is pictured in London artist George Andrews’s view of 1872. A coal keel is on the right, with its mast down so it could pass under the bridge. The old Tyne Bridge was replaced by the Swing Bridge, which opened in 1876.

The Swing Bridge, seen on the left of TM Hemy’s watercolour view of 1881, was designed and constructed by Sir WG Armstrong and Company Limited of Elswick, Newcastle, and cost £240,000 to build. The river was dredged at the same time. As a result, large vessels were able travel up-river and Armstrong could develop his armaments and engineering works at Elswick. Subsequently, the Elswick works began to build ships and other industry also developed.

The Swing Bridge, seen on the left of TM Hemy’s watercolour view of 1881, was designed and constructed by Sir WG Armstrong and Company Limited of Elswick, Newcastle, and cost £240,000 to build. The river was dredged at the same time. As a result, large vessels were able travel up-river and Armstrong could develop his armaments and engineering works at Elswick. Subsequently, the Elswick works began to build ships and other industry also developed.

Sir William Armstrong designed hydraulic engines to smoothly move the Swing Bridge, which weighs a massive 1,450 tons. In 1924, 6,000 vessels passed through the bridge. One group that suffered from the new bridge was Newcastle’s keelmen. Keels were easily able to pass under the old low bridge, and they were essential to carry coal (about 21 tonnes a load) to ships moored in deep water. With the bridge gone and river dredged, there was much less need for keels.

Sir William Armstrong designed hydraulic engines to smoothly move the Swing Bridge, which weighs a massive 1,450 tons. In 1924, 6,000 vessels passed through the bridge. One group that suffered from the new bridge was Newcastle’s keelmen. Keels were easily able to pass under the old low bridge, and they were essential to carry coal (about 21 tonnes a load) to ships moored in deep water. With the bridge gone and river dredged, there was much less need for keels.

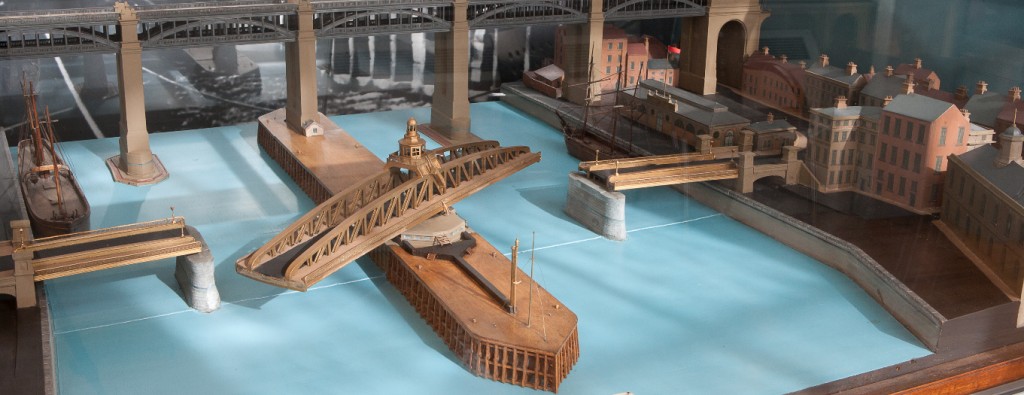

There’s a splendid model of the Swing Bridge on show in the ‘Story of the Tyne’ gallery at Discovery Museum, donated by the Tyne Improvement Commission. It shows a couple of sailing ships berthed up-river from the Swing Bridge, illustrating the better access it created.

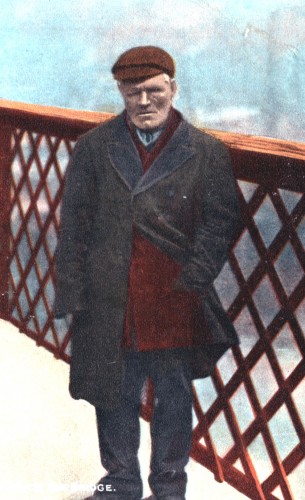

Tommy Ferrens, known as ‘Tommy on the Bridge’, was a fixture on the Swing Bridge for many years (and previously on the old Tyne Bridge). Blinded and partially paralysed by childhood illness, he had little choice but to beg for a living. Rain or shine, he stood rocking from foot to foot on the boundary mark between Newcastle and Gateshead in the belief that this made him immune from police attention from either area. His constant presence and his obstreperousness meant that he was considered a ‘Newcastle character’ at the time, and he featured on picture postcards like this one. He collapsed on the bridge on 1 January 1907 and died soon afterwards in Gateshead Workhouse Hospital from apoplexy and the effects of cold weather.

Tommy Ferrens, known as ‘Tommy on the Bridge’, was a fixture on the Swing Bridge for many years (and previously on the old Tyne Bridge). Blinded and partially paralysed by childhood illness, he had little choice but to beg for a living. Rain or shine, he stood rocking from foot to foot on the boundary mark between Newcastle and Gateshead in the belief that this made him immune from police attention from either area. His constant presence and his obstreperousness meant that he was considered a ‘Newcastle character’ at the time, and he featured on picture postcards like this one. He collapsed on the bridge on 1 January 1907 and died soon afterwards in Gateshead Workhouse Hospital from apoplexy and the effects of cold weather.

The High Level Bridge is Newcastle’s oldest existing bridge and still carries considerable rail traffic. However, transport needs have moved on. The Swing Bridge is only required to open occasionally, and now the Tyne Bridge and the new Redheugh Bridge have taken over the majority of local road traffic. Today’s through traffic completely avoids the Tyne Gorge, using the A1 Western Bypass or the A19 Tyne Tunnels.

Illustrations: Newcastle upon Tyne from Gateshead, 1895, by Niels Møller Lund (1863-1916); Robert Stephenson (1803-1859), photograph by Maull & Polyblank, London; High Level Bridge, 1848 (detail), engraving, drawn by John W. Carmichael (1799-1868), engraved by George Hawkins; Freeing the High Level Bridge, 10th May 1937, Tyne & Wear Archives DF.GRA/5/3, Photograph album, 10 May-August 1937; Newcastle from Gateshead (detail), 1881, watercolour by TM Hemy (1852-1937); Model of the Swing Bridge, about 1876; Tommy on the Bridge, about 1900, picture postcard: all, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums collections.

References: ‘£275,000 To Free Bridges’, North Mail, 10 April 1937 p9; http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Newcastle-upon-Tyne; https://www.newcastle.gov.uk/wwwfileroot/legacy/libraries/HistoryofNewcastlemainbody.pdf