My name is Ashleigh Jackson. I am a History undergraduate student from Edinburgh and I’m currently on a summer placement with the Natural History Society of Northumbria in their archives at the Great North Museum: Hancock.

“This morning Scarborough was touched for the first time by the Great War” – Marguerite Temperley, 16 December 1914

George W. Temperley was a member of the Natural History Society of Northumbria from 1906 until his death in 1967. Temperley was a talented naturalist, with particular interests in ornithology and botany. From 1913, Temperley lived in Scarborough, where he worked as Secretary to the Council of Social Welfare, witnessing the bombardment which occurred in 1914, killing 17 residents of the town.

The diaries of Temperley’s wife, Marguerite, offer a striking insight into the effects of the First World War on the Homefront. Her diary entry from 16 December 1914 records the fatal raid on Scarborough. The German Navy targeted the northern coast, including Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in the early hours of 16 December 1914. The ships opened fire with giant naval guns, desolating these quiet, coastal towns. During the bombardment 137 people were killed, while hundreds more were left injured and homeless as a result of the damage waged by the German fleet. Notably, Scarborough was vulnerable as it did not possess any gun defences and the harbour was not suitable for warships. However, German intelligence led them to believe that Scarborough, like Hartlepool, was defended by gun batteries which rendered it a legitimate military target under the rules set out by the Hague Convention of 1907.

Although the attack on the northern coast was not militarily significant, it did lead to significant loss and distress for the civilian population. An important impact of this event was the rise of young men enlisting, in an effort to avenge the devastation inflicted on their home towns.

A further impact of the raid was a loss of confidence in the Royal Navy, after many blamed its failure to intercept German intelligence and the inadequacy of coastal defence, leaving Scarborough and the other towns involved defenceless. In the immediate aftermath of the raid, there was an outpouring of public anger towards Germany, who they believed had broken the rules of war, for targeting undefended areas.

Tempereley was at home on the morning of the raid, preparing breakfast with his family when the bombardment began at around 8 o’clock. The Temperley family initially mistook the sound as thunder, but as the raid continued they soon realised it was something more sinister. The family, like many others across Scarborough were taken by surprise, and took shelter in their cellar. In her diary, Marguerite writes that her husband danced a highland fling in an effort to keep warm, a rather comic image in the midst of utter destruction.

Marguerite goes onto to describe the extent of the attack, with houses torn in half and roofs blown off while the already ruined castle suffered further damage. The image to the left shows Scarborough Castle, photographed soon after the attack. This section of the castle was hit by two shells during the raid, the scars of which are still visible today. The Temperley’s lived at 23 Esplanade Gardens, which survived the raid unscathed but this was located close to Royal Terrace where Marguerite notes a house had its roof blown open.

“As the bangs continued in quick succession we realised it was the sound of guns” – Marguerite Temperley, December 16th 1914

Notably, the Temperleys were both pacifists, however it remains unknown as to whether George was a conscientious objector. Local historian Joan Proudlock believes that George may have been a conscientious objector based on the research she has carried out, however, she emphasises that this is unclear. Furthermore, the nature of Temperley’s work in Scarborough remains ambiguous. Proudlock further suggests that Temperley’s work at the Council of Social Welfare was perhaps an alternative form of service during the war, rather than active service in the army.

During his time in Scarborough, Temperley began developing his skills as a lecturer, holding talks on natural history, ornithology and botany to local groups including the newly formed Women’s Institute. Soon after the end of the war, in 1919, the Temperley family moved back to Newcastle.

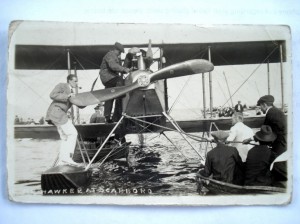

In 1913, the Temperleys witnessed the first biplanes taking off from Scarborough. The image to the right shows a postcard sent by George W Temperley to his uncle, Harry Charlton. He writes “this is the water plane that came to Scarbro! It is being oiled and overhauled ready for the next flight. You know it flew past Sunderland, then over Scotland and fell into the sea near Ireland and was smashed”.

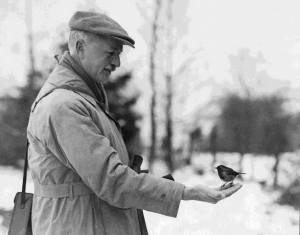

Upon his return to Newcastle, Temperley became an increasingly active member of the Natural History Society of Northumbria. He made extensive trips around the region, a commendable act for a man without a car. In 1927, he contributed to a series of ‘Young People’s Lectures’ giving a talk on 4 January entitled ‘Tales of the Birds’. It was not until he retired from social welfare in 1928 that his love of natural history was able to flourish. In 1930 he became the Honorary Secretary to the Society, and later, honorary curator to the Hancock Museum. From 1935, he began compiling an annual ornithological report for Newcastle and Durham, a task which was later inherited by Fred Grey after Temperley’s death in 1967.

Natural History Society of Northumbria ornithological field trip to Teeside, Temperley right. Image courtesy of the Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) Archive

The Natual History Society of Northumbria holds numerous archives relating to Temperley. The archives include Temperley’s diaries, natural history records and photographs, he remained a key member of the Society until his death, allowing both the Hancock Museum and the Society to grow even after the devastation of the First World War. Temperley acquired a reputation within ornithological circles, becoming well acquainted with Viscount Grey, George Bolam and Abel Chapman. In 1951, he published A History of British Birds of County Durham, the crowning achievement to his work as a naturalist.

23 March 1951 – Temperley can be seen to the far left ‘watching a flock of 250 Barnacle Geese and some Pink-footed Geese on the Solway Marshes’

Image courtesy of the Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN) Archive

[Quotations from Marguerite Temperley’s diary, taken from an unpublished biography by Joan H. Proudlock, ‘George W. Temperley, Botanist and Ornithologist 1875-1967′ (2016) held in the Natural History Society’s archive.]

One Response to George W. Temperley and the bombardment of Scarborough in 1914 – A Guest Post by Ashleigh Jackson