In Part 1 I looked at the origins of boat racing on the River Tyne and went on to explore the Tyne contribution to the invention and refinement of the outrigger, the bringing inboard of the keel, single strake (shell) construction and the refinement of foot steering for coxless pairs and fours.

In Part 2 I will move on to look at the development of the sliding stroke, followed by the adoption of the sliding seat, and also to what seems to have been the first bowloader coxed boat, racing in the Tyne Regatta in 1872, 80 years before the generally accepted first appearance of the bowloader, in Germany in the 1950s.

The sliding seat

As early as the 1850s, or most likely before that, Harry Clasper and his brothers were sliding on their fixed seats to give extra length and power to their stroke. Reports of their appearance at the 1844 Thames Regatta refer to “their peculiar style of rowing” (Newcastle Weekly Journal (NWJ) Saturday June 28th 1845) and “with a stroke peculiar to themselves” (NWJ June 29th 1844). To use the sliding motion an oarsman had to sit low in the boat, straighten his legs during the stroke by driving off the footboard, and perhaps most importantly, have his feet firmly strapped to the board so he could pull himself forward at the end of the stroke. This technique contrasted with that of sitting still on the seat, with almost all movement, and most power, coming from above the waist. The sliding on the fixed seat technique quickly became identified as the “traditional Tyne stroke”, but, even on the Tyne, some rowers slid hardly at all, while others, as contemporary reports put it, “made good use of the footboard”. Bob Cooper, “the Redheugh ferryman”, rowed at a high tempo which did not allow for much use of the legs, while the Champion sculler, Bob Chambers, made considerable use of his legs to row a long, powerful stroke.

Model of a fixed seat skiff (single scull) c.1860. This simple, but elegant, solid hulled model is representative of the type of boat used by Harry Clasper, Robert Chambers and James Renforth. TWCMS : B9758 Scale 1:12

There were a number of attempts to develop a sliding seat in the 1860s. Walter Brown, the American sculler who later beat William Sadler on the Tyne in 1869, tried one in 1861. A Dr. Schiller of Berlin made a slide using small wheels in 1863, but nobody achieved sufficient success to encourage the best oarsmen to switch away from fixed seat rowing.

Indeed, at this time there was not a general acceptance that sliding was superior to sitting still. Followers of rowing could see the benefits of the extra power and length of stroke, but weighed those against the effect on the “run”, or momentum, of the boat when an oarsman pulled his weight towards the stern to get in position to take his next stroke. It was also much harder to keep a crew rowing in time together if they were sliding as part of the stroke. After Harry Kelley of Putney, who sat still on his seat, defeated the North’s beloved Bob Chambers in 1865, those who favoured the straight-backed, non-sliding technique could justifiably claim that their method was as good as, or better than, the sliding technique developed on the Tyne.

Cockpit of a model of a fixed seat skiff (single scull) c. 1860. The seat is the long flat board that was required to use a sliding stroke on a fixed seat, although the footboard is missing. The frame which once held the footboard in position probably came adrift at the same time. Sadly, it appears that somebody has since glued this frame across the cockpit in a position that would have prevented the full-sized boat from being sculled! TWCMS : B9758 Scale 1:12

The arrival of James Renforth on the scene quickly began to alter opinion. At first observers declared his stroke ugly – The Daily Telegraph dubbed him the “Radical” oarsman – but they soon recognised the effectiveness of his thigh-thrusting, leg-driving, bottom-sliding technique. His unbroken string of victories in all boats; single sculls, pairs and fours, forced the pundits to accept that Renforth’s stroke was better for winning races than the seemingly more stylish techniques employed by his opponents.

A reporter writing for Bell’s Life after Renforth’s victory over Kelley in November 1868 put it like this:

“One very notable feature of his style is the great use he makes of his legs; indeed, we have no hesitation in saying that we never met with a sculler, not even excepting the late Bob Chambers who so fully understood the important art of bringing every muscle together with the full weight of the body to bear on every stroke; and we are satisfied that this is the great secret of his wonderful turn of speed, which enabled him to vanquish such a “flier” as Kelley.”

Having run out of opponents willing to take him on in single sculls, Renforth increasingly rowed as stroke oar in pairs and fours. Men who came into his boat had to adapt to his style.

James Renforth shown on the River Tyne in his skiff. This print was probably produced after his death in 1871. David Clasper

Renforth’s dominance had its effect on those who were trying to develop a successful sliding seat. The campaign to North America in 1870 and the victory at Lachine seems to have influenced the Americans, and in particular J C Babcock of the Nassau Rowing Club of New York, a champion oarsman and sculler. Babcock had experimented with a slide in 1857 but did not consider it a success. In 1870 he tried again and this time was pleased with the results that he obtained with a trained crew. Novices however, found it more difficult than fixed seat rowing.

Babcock’s slide used a seat which was a 10 inch-square wooden frame covered with leather and grooved at the edges to slide on two brass tracks fastened on the thwart, allowing a slide of 10-12 inches. The tracks were lubricated with lard and gave a ‘rowing’ length of slide of up to 6 inches. Babcock wrote a letter about the slide to Waters Balch on 14 December 1870, which shows how Renforth’s 1870 crew was influencing his thinking. It concludes:

“The slide properly used is a decided advantage and gain of speed, and the only objection to its use is its complication and almost impracticable requirement of skill and unison in a crew, rather than any defect in its mechanical theory. When we take into consideration that the best oarsmen in the world, the Tynesiders, slide, when spirting, from four to six inches on a fixed seat, the moveable seat can only be considered as a mechanical contrivance, intended for a better accomplishment of the sliding movement in rowing.”

By 1871 American professionals were successfully using slides of the Babcock type in races, notably at Saratoga, and at Halifax, Nova Scotia, where they competed against Winship’s crew and Chambers’ crew, which was made up of the remaining four from Renforth’s crew, following Renforth’s untimely death. The Biglin crew competed using slides at Saratoga in both the fours and the sculls races. They did not win, but then neither did either of the English crews. Ironically the fours race was won by the Ward brothers, rowing in Dunston-on Tyne, the Jewitt-built fixed seat boat in which Renforth’s crew had triumphed at Lachine the previous year.

After competing in regattas at Saratoga, Longueil, Halifax and Quebec, the two predominantly Tyneside crews – Joe Sadler was the Londoner in Winship’s crew, and Harry Kelley rowed in the Chambers crew – returned to England. They received great receptions, with an estimated 10,000 people turning out to greet the Chambers crew at Newcastle. Hostilities resumed almost immediately. A four-oared race for £400 (the 2017 equivalent might be as much as £330,000) was set to take place on the Tyne on Wednesday 22nd November and both crews went back into training. The races in North America had not conclusively proved which was the better of the two. The only way to decide was in the traditional manner, with a match over the Tyne Championship course.

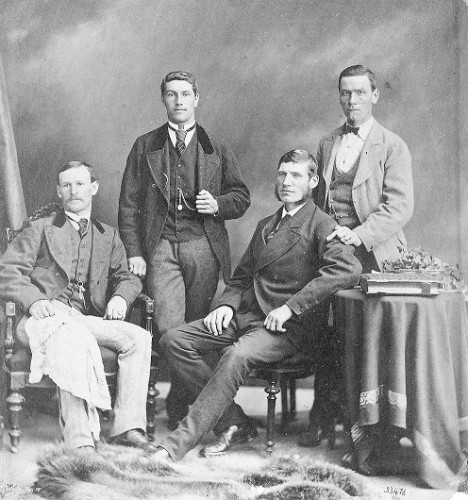

Photograph of the Winship Four 1871 taken in the USA or Canada when this crew competed in a number of regattas during the summer. From the left, Thomas Winship (stroke), Robert Bagnall (3), Joseph Sadler (2) and James Taylor (bow). Gateshead Libraries

When the two crews appeared at the start the Winship four, rather surprisingly, were rowing with slides. These worked on the same principle as those of American design they had encountered across the Atlantic, but they had front and back stops to prevent the seat from becoming detached from the slide, and the slides were made of steel. The crew had only used them for the first time the day before the race, but they had obviously concluded that the risk of using the sliding seats was worth taking, despite their lack of practice with them. One detects the hand of James Taylor, the inveterate experimenter, in the decision to row with slides but there is no mention in the race report that he was behind this bold choice. It seems exceptionally bold when one considers the huge sum of money riding on this one race.

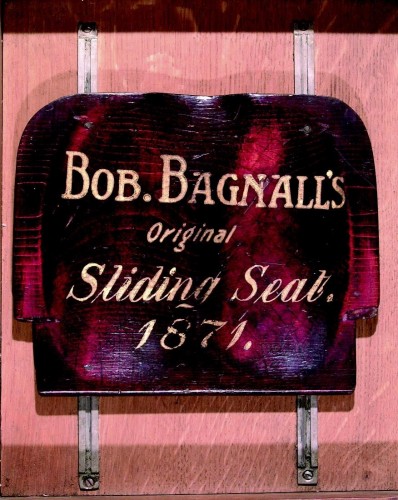

Robert Bagnall, then aged 22 and, following the death of Renforth, the best Tyneside sculler in training, rowed behind Winship at 3. The seat and slide which he used in this historic race is on display at Discovery Museum, Newcastle.

This is the seat that Bagnall used when part of the Winship crew that took the four oared Championship of the Tyne on 22 November 1871. Bagnall was 22 years old, weighed 10 stone 7 lbs and was 5 feet 8 inches tall. TWCMS : E7199. Discovery Museum

In the event they won the race, completing the destruction of the former Renforth crew and ensuring that oarsmen throughout Britain would swiftly adopt the use of sliding seats. Tynesiders had probably been sliding on their seats since the 1840s, but henceforth they would be sliding with their seats. They could also look forward to less trouble with boils on their buttocks – something that Percy had suffered from in the run-up to this race.

The Newcastle Daily Chronicle of Thursday November 23rd 1871 in its conclusion to the race report put it thus:

“The result of this contest will most probably be the adoption of the sliding seat, at least in fours, and perhaps in pairs and skiffs as well.”

Although this reflects a rather Tyne-centred view of the rowing world, the success of Renforth and his companions over the previous three years did seem to justify opinions such as these.

The development of a practical slide is quite rightly assigned to Babcock. However, Renforth’s success with a stroke which manifestly involved sliding considerably, albeit on a seat rather than with a slide, encouraged Babcock and his contemporaries to press on with their experiments. Renforth was so dominant after November 1868, in all boats, that his technique was recognised as providing significant extra power from the legs. The Tyne has no claim on the invention of the slide but Babcock’s letter of 1870, acknowledging that the Tynesiders were the best oarsmen in the world, and that he was only trying to achieve mechanically what they did when they slid on their seats, shows the influence that Renforth and his crews had on Babcock’s thinking.

A Tyne bowloading coxed four 1872

It has been generally accepted in the rowing world that the first boats to feature a coxswain positioned in the bow were pair oars, developed by Georg von Opel in Germany in the 1950s. The new arrangement was immediately successful and the practice soon spread to fours. However, while looking at contemporary news reports of the Tyne Regatta of July 1872 I came across an account of a bowloading four that won the professionals race and a prize of £50 (worth perhaps £5,500 today (2018). The boat had to win a heat before progressing to the final, so it was no fluke, and there was serious money at stake! But, just as interesting as the victory itself is the sequence of events that led to the decision to position the cox in the bow.

You may recall from part 1 of this blog that the Canadian St. John crew won the amateurs race at the Great International Regatta in Paris in 1867 in a foot-steered, coxless four. James Taylor was a member of the Tyne four that won the professionals race at the same regatta so had an opportunity to observe the steering mechanism. Eighteen months later Taylor fitted foot steering to a pair and, rowing with James Renforth, defeated Matthew Scott and Andrew Thompson on the Tyne for a stake of £50 a-side.

When, in 1870, the St John crew challenged the Tyne Champion Four to a race in Canada the match was made in coxless fours. The Tyne men won, but a new challenge came from St John in 1871 and once again the match was made in coxless fours. The Tyne Champion Four lost the race when James Renforth collapsed shortly after the start of the race and died a few hours later. However, following this tragedy, the rest of the crew and another crew made up three Tyne men, James Taylor, Robert Bagnall and Tom Winship, plus the Londoner Joseph Sadler, contested coxless fours races at Saratoga, Longueil, Halifax and Quebec. Thus, the top Tyne professionals became familiar with racing in coxless boats in North America. When the Taylor – Winship crew returned home and agreed articles to race against Renforth’s old crew for the Championship of the Tyne the match was made in coxless boats. Both crews had matching new boats built by Robert Jewitt. The Taylor-Winship boat, The Adelaide, was built with no room for a cox in the stern and it was fitted out with sliding seats. The other boat was named The Renforth.

The Taylor-Winship crew duly won the Championship of the Tyne on Wednesday 22nd November 1871 and in its closing remarks the Chronicle predicted, “It is in every way likely that the Renforth four will now dissolve partnership”.

The successful Taylor-Winship crew remained together for the 1872 season and at the beginning of July were preparing to race at the Tyne Regatta. As expected, the Renforth four had broken up, but a new four had formed around two of its former members, the veteran Harry Kelley in the 3 seat and James Percy in the bow seat. This was known as the Blenheim crew, named after the public house that Harry Kelley was now running in Newcastle.

Photograph of the Renforth Four (with spare man) 1871. Clockwise, from left, James Percy (bow), Robert Chambers (from Wallsend) (2), Harry Kelley (3), James Renforth (stroke) and John Bright (spare man). The Blenheim crew that contested the fours race at the Tyne Regatta included James Percy (bow) and Harry Kelley (3) but Thomas Matfin replaced the late James Renforth at stroke, and Ralph Hepplewhite was at (2) in place of Robert Chambers.

David Clasper

These two crews were the favourites for the regatta’s prime race for professionals.

“ NORTHUMBERLAND STAKES, a four-oared race, with coxswains, open to all. Prizes: First boat, £50; second boat, £20; third boat, £10. Entrance, 2s. 6d. per oar. Distance one mile and a quarter.”

The Northern and Albion Rowing Clubs had also entered crews so four boats would be competing for the £50 prize.

The Tyne Regatta was largely administered and managed by senior figures from the Tyne Amateur Rowing Club. This provided an intriguing aspect to this contest, because, at a time when amateurs and professionals were increasingly going their separate ways, two hardened professional crews would compete according to rules set and interpreted by amateurs. Six of the eight members of the top crews had raced for the Tyne Championship in coxless boats less than a year previously, with the match rules set out in the articles they had signed. Now they would have to abide by the rules of the Tyne Regatta. A few days before the race, James Percy, Renforth’s old bow man, and a member of the Blenheim crew, smelt a rat, and gave voice to his suspicions at a meeting of the regatta committee.

The Newcastle Daily Chronicle’s description of the meeting explains the issue clearly:

“In answer to a question from James Percy, the committee decided that the coxswain might be carried upon whatever part of the boat the crew thought fit, only he must use the lines and steer, and be six stones in weight; or provided that he is not that weight, he must carry the requisite amount of lead upon his seat only. The question by Percy was prompted by “information received”, that the Taylor-Winship four, who intend to row in the boat they occupied when they won the championship last November, and which, it will be remembered, has no coxswain’s seat, propose to put the steering-boy at the fore end of the craft instead of the aft.”

Newcastle Daily Chronicle Monday July 15th 1872

The Taylor-Winship crew would row in The Adelaide, and the Blenheim crew would use The Williamson, a Jewitt-built four belonging to South Shields ARC. The Chronicle says the boat was a little small for them, and I think one must assume that the Blenheim crew had not able been able to secure the use of The Renforth for this race.

The first heat for the Taylor-Winship crew was against the Northern Rowing Club four and the positioning of the coxswain in The Adelaide was attracting a great deal of interest from the spectators.

“The object of all the attention was the peculiar mode of carrying the coxswain adopted by the Taylor-Winship crew. Little Wilson, [Thomas] instead of being seated in the usual coxswain’s seat, was accommodated in the forward part close to the bow oar, but looking to the stem of the boat. “The Adelaide” was built, it will be remembered, for use without a coxswain, and the means adopted to comply with the regulation of the committee, it was observed, were such that Taylor touched the coxswain with his back at the finish of nearly every stroke, so that in consequence the general verdict was against the efficiency of the new plan.”

Newcastle Daily Chronicle Saturday 20th July 1872

The coxswain, Thomas Wilson, was well known to rowing supporters on both Tyne and Thames. In November 1869, he had brilliantly steered Renforth’s champion four to victory over the Thames men twice in matches, first on the Thames and two weeks later on the Tyne. At that time Wilson was aged 14 and weighed in at 54 lbs for the first match and 56 lbs for the second. (Whitehead, I, James Renforth etc. P75 – 80) Now aged 17 he might have reached the minimum 6 stone (84 lbs) weight specified by the committee, but if not, he would have had to make up the weight with lead positioned on his seat. James Taylor was a key member of Renforth’s champion four in 1869 and would have been confident in Wilson’s ability to adapt to his new situation.

Rowing Colour of the Tyne Champion Four 1869. This colour was issued to mark the home and home races of the Tyne Crew, against a London crew, in the autumn of 1869. It features the Newcastle coat of arms and lists the Tyne Crew, (James) Taylor, (Thomas) Winship, (John) Martin, (James) Renforth (Stroke), (Thomas) Wilson (cox). The Tyne men won both races with the boy coxswain Wilson distinguishing himself on each occasion. TWCMS : 2011.3448. Discovery Museum

Whatever the “Chronicle’s” view of the general verdict against the efficiency of the new steering arrangements, the Taylor-Winship crew won their first heat, defeating the Northern Rowing Club easily by four lengths. As was expected they later contested the final against the Blenheim crew. Once more they gained a comfortable victory, winning by a margin of four lengths. On this evidence one wonders why the bowloader didn’t catch on in the 1870s, or at any time after that until it resurfaced in the 1950s.

Maybe it was because the circumstances of its appearance were rather unusual. James Taylor and Thomas Winship both raced regularly in coxless fours in America in 1870 and 1871. Back on their home river they won the Championship of the Tyne in the coxless four, The Adelaide, in November 1871. The Adelaide was at their disposal to use at the Tyne Regatta, but the professional race was for coxed fours. They didn’t want to give up the chance of racing in their winning boat so they adapted it to accommodate the trusted and resourceful coxswain, Thomas Wilson.

There is the possibility that the bowloader did catch on before the 1950s, but was not widely known about. After all, I only came across its appearance on the Tyne in 1872 when it caught my eye while I was researching something else. Does anybody out there know of a reappearance of the racing bowloader before its introduction in Germany in the 1950s?

Bibliography

Clasper, David, Harry Clasper Hero of the North, Gateshead, 1990.

Clasper, David, Rowing: A way of life, The Claspers of Tyneside, Gateshead 2003

Dillon, Peter, The Tyne Oarsmen, Newcastle 1993.

Dodd, Christopher, The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, London, 1983.

Dodd, Christopher, The Story of World Rowing, London, 1992

Whitehead, Ian, The Sporting Tyne, A history of professional rowing, Gateshead 2002

Whitehead, Ian, James Renforth of Gateshead, Champion Sculler of the World, Newcastle 2004