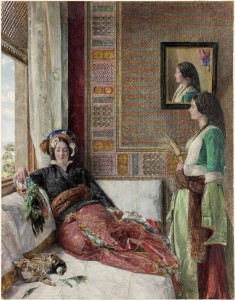

Surrounded by tell-tale feathers, this little cat raises a paw, ready to strike again. Its prey is actually a peacock-feather fan, which a young woman is dangling teasingly above its head. Both the cat and its owner feature in an outstanding watercolour, Hhareem Life, Constantinople by John Frederick Lewis, which is on show in Watercolour Stars at the Laing Art Gallery until November 25th, and then in Painted Faces from December 5th through summer 2013.

Those markings on the cat’s shoulder are discs of sunshine filtered through a window lattice. The complex changes of colour on the animal’s fur and the white couch-cover show just how skilled JF Lewis was at depicting the fall of light.

The influential Victorian art critic John Ruskin considered that JF Lewis’s watercolours were comparable to those of the Pre-Raphaelite painters for ‘truth to nature’. The fantastic details and colours of Lewis’s pictures made them enormously popular with audiences of his day, who were also fascinated by his exotic sun-filled subjects from lands far away.

The little cat in Lewis’s picture created a bond with those viewers who would have seen their own cats behaving the same manner. But Lewis had another way of inviting viewers to connect imaginatively with the scene – he included a pair of legs reflected in the mirror on the wall – they are probably intended to represent the artist or even ourselves.

Lewis painted his picture in tremendous detail, giving all the aspects almost equal attention, in the manner of the Pre-Raphaelite artists. Lewis used gouache (watercolour mixed with white pigment) to create his brilliant colours, with white paint for some highlights. The details were ‘true to nature’ in the sense that they were carefully studied from real objects, but this was not a real-life scene. Lewis certainly never entered the women’s rooms of a harem (Lewis’s spelling of hhareem was intended to reflect Eastern pronunciation of the word). His model for one or both of the women was probably his wife, Marian, whom he married in 1847 and who appears in many of his pictures. It’s likely that he based the room setting on sketches of his Cairo home, where he was living in the 1840s, though he probably added extra decoration.

Lewis painted his picture in tremendous detail, giving all the aspects almost equal attention, in the manner of the Pre-Raphaelite artists. Lewis used gouache (watercolour mixed with white pigment) to create his brilliant colours, with white paint for some highlights. The details were ‘true to nature’ in the sense that they were carefully studied from real objects, but this was not a real-life scene. Lewis certainly never entered the women’s rooms of a harem (Lewis’s spelling of hhareem was intended to reflect Eastern pronunciation of the word). His model for one or both of the women was probably his wife, Marian, whom he married in 1847 and who appears in many of his pictures. It’s likely that he based the room setting on sketches of his Cairo home, where he was living in the 1840s, though he probably added extra decoration.

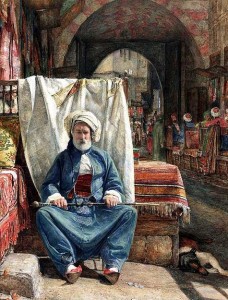

Lewis lived for a nearly a year in Istanbul (then known as Constantinople), in Turkey, in 1840-41, and then spent nine years in Cairo in Egypt. In Cairo, Lewis immersed himself in local life, wearing traditional clothing and living in a grand 16th-century house. Lewis often put himself in his Middle Eastern scenes – his watercolour of a carpet seller is a self-portrait. Lewis brought back sketches, fabrics and objects when he returned to England in 1851. He didn’t actually paint Hhareem Life, Constantinople until six years after his return, at his home in Surrey. (Lewis’s pick and mix approach to his compositions is shown by the way he reused the woman’s green jacket in a scene painted a year later, which was supposedly set in Cairo rather than Constantinople.)

Other JF Lewis paintings can be seen on these web pages – Victorian web, Tate, Victoria and Albert Museum, and Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery (best check with the museum before visiting if you would like to see them).