With the temporary closure of the Great North Museum: Hancock due to Covid-19, visitors cannot physically access our current exhibition Ancient Iraq: new discoveries, which highlights some amazing archaeological stories from that country.

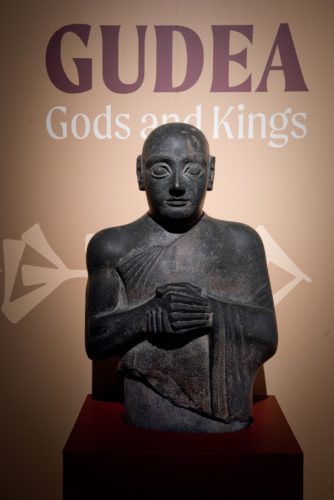

Statue of King Gudea; dolerite; Tello, Iraq; 2130BC © The Trustees of the British Museum. This object features in the exhibition Ancient Iraq: new discoveries.

As a museum curator I was lucky enough to visit Iraq in January 2019 as the guest of several Iraqi universities who were interested in the work the Great North Museum does to bring its archaeological collections to life for school children. I delivered presentations and visited a number of universities in the south of Iraq, including Babylon, Wasit and Kufa. At the same time I was able to see some key archaeological sites as well as enjoying Iraqi hospitality. I thought I would share some of my photographs from that trip as a way of bringing Iraq’s wonderful archaeological heritage to light while our exhibition is inaccessible.

One of the most famous archaeological sites in Iraq, which I was fortunate enough to visit, is Bablyon. It was an urban centre that came to prominence during the reign of Hammurabi (about 1792 – 1750 BC) and went on to become one of the major powers in the region.

The original Ishtar Gate was built by the Babylonian King Nebuchadnnezar II in about 575 BC. This reconstruction is about half the size of the original gate and was constructed during the rule of Saddam Hussein. Saddam was interested in developing Iraq’s archaeological sites as showcases for his regime and massive reconstruction projects were carried out throughout Iraq.

The mušḫuššu was a mythical creature combining the talons of an eagle, lion-like forelimbs, with a long neck and tail, a horned head, a snake-like tongue, and a crest. They were placed on the walls of Babylon as protection for the city.

Another important site I visited was Ur. One of the very first cities in the world and a key centre for the Summerian civilization. It is famous for its massive ziggurat, a temple built to the god Nanna in about 2100 BC, by Ur-Nammu the King of Ur.

The ziggurat is a massive platform built of mud brick to honour Nanna, the Mesopotamian god of the moon and wisdom. Like Babylon this site was extensively reconstructed during the rule of Saddam Hussein.

As well as visiting archaeological sites I took a trip to the marshes in Southern Iraq. These were at one point one of the largest wetland areas in the world. The Marsh Arabs who lived there practiced a unique way of life that, in many respects, was unchanged from that of the ancient peoples of Iraq. Large areas of the marshes were drained during the rule of Saddam, who saw them as a place where opponents of his regime could hide out. This was an ecological catastrophe, destroying a unique habitat that was home to diverse wildlife as well as the Marsh Arabs. More recently there have been attempts to reflood areas of the marshes and there are still communities of Marsh Arabs clinging to aspects of their old way of life. The marshes were one of the highlights of my visit to Iraq. They gave me a profound sense of peace and tranquility. I can only imagine what they must have been like when they covered a significant part of southern Iraq.

Buffalo have been kept in the marshes as an important source of food since ancient times. A creamy cheese, made from buffalo milk, is still commonly eaten in Iraq.

Mudhif houses are where the Marsh Arabs entertain their guests. They are built with techniques that date back to some of the very first buildings in Iraq.

Another highlight of my visit was seeing the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. This museum suffered a great deal after the coalition invasion of Iraq in 2003. The museum was extensively looted, with many objects from its collections smuggled out of Iraq. Through the efforts of its staff and support from throughout the world the museum has recovered many objects and is again open. It really is a treasure house that displays the sheer wealth of Iraq’s archaeological heritage.

The Lady of Warka, also known as the Lady of Uruk, dating from 3100 BC, is one of the earliest representations of the human face. It is probably an image of the goddess Inanna, who was associated with numerous things, including love, war and political power.

Gertrude Bell, who was born in Washington County Durham, founded the National Museum in the 1930s as well as writing Iraq’s first Antiquities law.

One of the most encouraging things I saw in the National Museum was a group of young Iraqis meeting to discuss their country’s heritage. They clearly care a great deal for this and engaged in a lively discussion about what it meant to them.

Throughout my visit I was made to feel most welcome. There was vast quantities of food, including plenty of river fish and rice, as well as salads, flat bread and buffalo cheese.

I also quickly became used to the Iraqi habit of wanting to have their photograph taken with you at every possible moment. I must have posed for hundreds of pictures during the visit.

This is one of my favourite pictures. These young Iraqis have a distinct sense of style, particularly their haircuts.

Iraq is a country facing many challenges and it has a great distance to travel before the damage of over twenty years of conflict can be repaired. Nevertheless I was impressed with how enthusiastic Iraqi’s were about their country’s archaeological heritage and their willingness to share it with the rest of the world. Hopefully there will still be time to see the remarkable objects from Iraq in the Great North Museum and find out more about the British Museum’s efforts to support the preservation of Iraq’s heritage.

A statue in Baghdad symbolising Iraq’s desire to repair its damaged archaeological heritage. A many handed figure is reparing a broken cylinder seal.

As a charity, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums rely on donations to provide the amazing service that we do and our closure, whilst necessary, has significantly impacted our income. Please, if you are able, help us through this difficult period by donating by text today. Text TWAM 3 to give £3, TWAM 5 to give £5 or TWAM 10 to give £10 to 70085. Texts cost your donation plus one standard message rate. Thank you.