One of my guilty pleasures in life is watching Disney films. When the new offering Moana was released recently, I enjoyed whiling away a rainy Sunday afternoon watching the adventures of characters who lived far, far away and many centuries in the past. The basic plot of the story involves a young Polynesian girl, Moana Waialiki, venturing out onto the ocean to restore the heart of the goddess Te Fiti in order to save her island, which is slowly dying. This mystical heart took the form of a greenstone amulet, and it had been stolen 1000 years earlier by Maui, a demi–god. Along with her charmingly daft chicken HeiHei, Moana sets sail to find Maui and recruit him to assist her in returning the heart.

By the end of the film, my curatorial interest was piqued. How authentic was the story being told? Was it based on real Polynesian history? I decided to do a little bit of research into Polynesian culture, and as the ethnographic collections at the GNM: Hancock are particularly rich in material from the Pacific Islands, I knew there would be some fascinating objects that would bring the stories and legends to life.

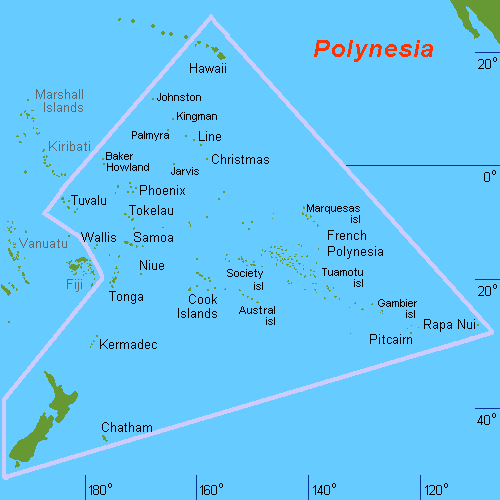

Map showing the vast area of Polynesia, with Hawaii in the north, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in the south east, and New Zealand in the south west. Polynesia consists of over 1,000 islands.

One of the main themes of Moana is about seafaring and navigation. In the movie, Moana’s island people never venture beyond the reef into the open ocean, and yet she discovers that at some point in time, her ancestors were great seafarers. This highlights a key period of Polynesian history. It’s now known that western Polynesia was colonised about 3,500 years ago, but the islands of central and eastern Polynesia were not settled until about 1,500-500 years ago. This means that after arriving on islands such as Fiji, Samoa and Tonga, Polynesians took a break of almost 2000 years before voyaging onwards. This time in history is known as “The Long Pause”, and no-one is sure why this happened, or what made the Polynesians begin their seafaring expeditions again. In Moana, The Long Pause comes to end when a fleet of canoes set forth across the ocean, the islanders having been inspired by the heroine’s journey and achievements. The story of this oceanic navigation and migration is an amazing one and fundamental to Polynesia’s history. This relationship with the sea and importance of sea going vessels is reflected in the many Polynesian canoe parts and model boats in our collections at the GNM.

NEWHM : C573, model canoe with outrigger, Niue . Part of a bequest from the late Julia Boyd, a keen collector of natural history and ethnographic artefacts.

NEWHM : C589, Maori canoe paddle, New Zealand. Acquired in 1769, possibly on James Cook’s first circumnavigation of the globe.

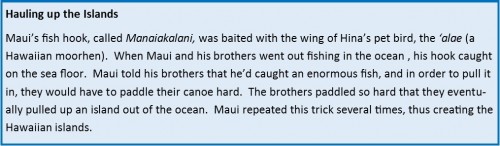

Disney’s take on the demi-god Maui is another noteworthy aspect. Maui is indeed a prominent character within Polynesian legends, but the portrayal of him in the film has come in for serious criticism. Maui was traditionally a lithe teenager on the verge of manhood, but the film shows him as an enormous man. While some critics have pointed out that this version of Maui perpetuates the image of Polynesians being overweight, his appearance is not the only thing that’s different. In Polynesian culture, Maui was always accompanied by the goddess Hina who featured as his sister, wife or mother in various stories. In Polynesian lore, the association of a powerful goddess with a god creates symmetry and harmony– indeed, it was Hina who enabled Maui to accomplish many of his legendary feats. In Moana, Hina has been omitted completely. Maui’s famous fish hook however, has been included. This magical tool allows Maui to accomplish all kinds of amazing feats, including in one famous Polynesian legend, the creation of the Hawaiian islands.

In Moana, the heart of Te Fiti is represented as a greenstone amulet. The use of greenstone for such an important amulet is very appropriate. “Greenstone” is the generic name given to nephrite jade, a beautiful rocky mineral that is only found on the South island of New Zealand. The Maori name for this material is pounamu, and it plays a very important role in Maori culture as it is considered a taonga, or treasure. The most prized taonga are those with a history going back generations as these are believed to have their own mana (effectiveness, prestige, power– often of a supernatural variety). Typical pounama taonga are more likely to be tools such as adzes and knives (as opposed to hearts of goddesses) and we are lucky enough to have several greenstone objects in the GNM: Hancock collections. One of the most striking items is an adze blade. It’s thought that this blade may have been produced in the 18th century, and it was found when it was turned up by a plough near the site of an old Maori pah– a fortified place. Quite possibly this was once a valued taonga.

Before Moana jumps into her boat to venture out in the open ocean, there’s many a scene showing island life and what can be seen repeatedly, in various forms, are displays of barkcloth. Known as tapa, Pacific islanders have made this cloth from the bark of trees for millennia. It could be used for many different things such as room dividers and wall hangings, marking sacred spaces, and also as clothing where it was seen as a “second skin”- a wrapping that reinforced and contained the self, and bounded the flow of sacred energy. These barkcloths are renowned for their exquisite decorations, as many show dazzling motifs, patterns and vibrant colours. In Moana’s village, tapa can be seen many times– the credits in the film even scroll over a piece. When Europeans first began to encounter this form of art in the 18th century, they were highly impressed by it and began to collect it in large quantities and ship it back to Europe. These pieces of barkcloth are now in museums and private collections all over the world, including the GNM: Hancock. We have a vast array of barkcloth samples of all sizes, and our pieces on display in the World Cultures gallery show beautiful designs and colours.

NEWHM : C603, barkcloth with floral motif, Samoa. The letters painted on the edge read “Simeauli F. i. Pago Pago” which means made by Simeauli of Samoa.

NEWHM : C702, Panel of striped barkcloth, Hawaii. This piece has been made from the inner bark of the paper mulberry tree, broussonetia papyrifera.

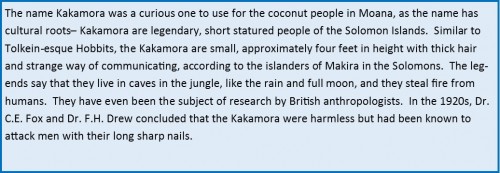

Lastly, a note about the “coconut people” in the film, who were called the Kakamora. Moana came into contact with these pirates on the high seas, and they were depicted as mean little coconuts (complete with arms and legs). These little characters were very intriguing. Could it be possible that they were a simple, cartoonish depiction of the mighty Kiribati warrior? The Kiribati Islands, while technically a part of Micronesia, are dispersed over 1.35 million square miles and so many of the atolls and islands of Kiribati can actually be found deep within Polynesia. As all of our visitors to the World Cultures gallery will know, Kiribati is famous for producing amazing armour made out of coconut fibre.

Kiribati is mainly formed out of low lying coral atolls, meaning that few raw materials were historically available. Coconut plants, however, were plentiful and were thought to possess special protective powers, so armour was woven together from coconut fibres. Could the idea of Moana’s little coconut pirates have originated from these coconut clad warriors from Kiribati ? Well, that’s my theory.

On a side note, while exploring the ethnographic collections to try and explain about Moana’s coconut people, I came across a couple of objects that initially led me to think that they had been more of a literal depiction than I previously thought…

But alas, this jovial duo originated from Jamaica, over 5,000 miles away from Polynesia. I’m sure they have their own story. Maybe one day we’ll see a Disney film about it…

One Response to Exploring Moana at the GNM: Hancock