Work on the project has been progressing smoothly for the past month. Colin has now completed the cataloguing of the Bartram & Sons ships plans we hold and has started work on the plans of the Sunderland shipbuilding firm of John Crown & Sons Ltd.

While Colin has been keeping out of mischief (mostly), I’ve been working on the records of Austin Pickersgill Ltd and its two predecessor companies, S.P. Austin & Son Ltd and William Pickersgill & Sons Ltd. Most of the documents catalogued so far are typical of the shipbuilding records we hold and include annual reports, hull and engine specifications, contracts and ships cost files. However, a number of slightly unusual documents have also been unearthed. By a strange coincidence these all touch on the topical subject of credit.

Of particular interest is a series of records relating to the iron barque ‘Mary Roberts’, launched by William Pickersgill & Sons in 1887. The vessel was built for the Liverpool shipowner Richard Hugh Roberts. However, when Mr Roberts defaulted on his payments to Pickersgills in 1888 the firm set about repossessing the vessel. With the agreement of the ship’s other shareholders Charles Pickersgill was appointed manager of the ‘Mary Roberts’ and personally travelled to Hamburg in October 1888 to take possession of her. The ‘Mary Roberts’ completed its scheduled voyage and was then sold in December 1889 against the wishes of the previous managing owner, Mr Roberts.

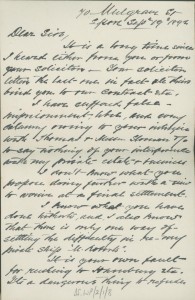

It appears that Charles Pickersgill may have been pretty ruthless in his dealings with Roberts, who certainly had hard feelings about his treatment. In a letter to William Pickersgill & Sons in 1892 Roberts wrote, “I have suffered false imprisonment … and every calumny owing to your intrigues with Thomas & Messrs Sloman & Co to say nothing of your interference with my private estate & business”.

The shipowner’s difficulties are also mentioned in a letter by Charles Pickersgill dated 11 February 1889 (TWAM ref. DS.WP/2/1/5) in which he passed on a report that Roberts was “still in a Lunatic Asylum”.

On the other hand, letters written in August and September 1888 (TWAM ref. DS.WP/2/1/3) by Captain Owen Lewis, the master of ‘Mary Roberts’, paint a slightly unflattering picture of Roberts’ behaviour and he certainly doesn’t appear to be blameless in his misfortune. The events surrounding the repossession and sale of the ‘Mary Roberts’ are intriguing and I hope that further research might one day shed more light on them.

The records of S.P. Austin & Son Ltd also contain a number of unusual items. A document that particularly caught my eye is a register of enquiries of the credit status of potential customers, kept between 1884 and 1927 (TWAM ref. DS.AP/3/4). The vast majority of the entries give a positive account of the potential clients. An interesting example is the entry dating from 17 September 1902 for C.S. Swan & Hunter of Wallsend, who were interested in ordering a pontoon. The enquiry into the firm’s creditworthiness concluded “that they are safe and have a lot of good work in hand”. History confirms that the firm went on to great things.

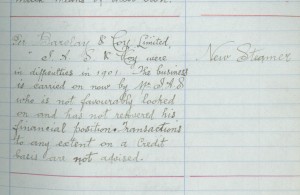

Not all reports are glowing, though, as is reflected by an entry dating from 26 November 1902 for J.A. Salton & Co. of 31 Lombard Street, London. The report sent by Barclay & Co. Ltd mentions that the firm “were in difficulties in 1901. The business is carried on now by Mr J.A.S. who is not favourably looked on and has not recovered his financial position”.

This register is also interesting because it includes details of proposed ship repair work. Ship repairing was an important part of the firm’s business but is poorly documented in the collection. Austins was well known for its Pontoon Dock, completed in 1903, which allowed the firm to carry out larger repair jobs on vessels up to 400 feet in length.

Over the next few weeks I’ll be completing work on the S.P Austin & Son and William Pickersgill & Sons collections. These include some interesting personnel records and I look forward to reporting on them in my next blog.