Turner showed the castle apparently cut off by sea – a way of expressing its isolated and exposed location. It’s possible to get that kind of view from rocks at high tide, but only if you don’t turn your head too much to the left, when you’d see the curve of the shoreline. The castle walls extend along a long, thin finger of land that sticks out into the sea.

Visiting Dunstanburgh today, the gigantic double-towered gateway and ruined towers are some of the most striking features of the castle. The steep hill and sheer cliff on the far side of castle also make quite an impact. Turner’s watercolour takes liberties with the actual view but in a way that expresses the character of the place.

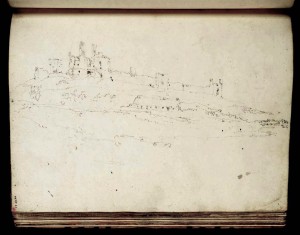

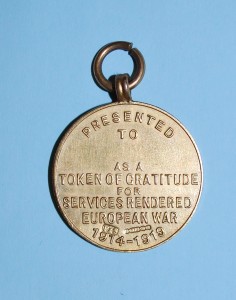

Turner made only one drawing of the main front of the castle in his 1797 sketchbook, and it’s very similar to the view in the photograph. Turner’s pencil sketch is very faint, so the image has been enhanced to make it a little easier to see. In the sketch, we can see the outline of the dark green bank below the castle – it’s covered in low-growing gorse bushes, and probably hasn’t changed much since Turner’s time.

Dunstanburgh Castle from the South 1797, Tate D00952. Photo: © Tate, London 2012, enhanced image. Click the image to enlarge

The main difference to the photo view is the closeness of the Lilburn Tower (on the left) to the entrance gateway. This has the effect of giving a more unified appearance to the castle front. I don’t think it’s possible to get a view from the shore that shows the Lilburn Tower like this – I’ve tried and failed. So, I think that Turner was already making picture composition choices in the sketch.

I’m pretty sure also that the cottage was a pictorial invention, added to contrast with the ruined grandeur of the castle. The land there is marshy – the remains of a medieval lake that was dug in an arc around the landward sides of the castle – and there’s no evidence of a cottage on the ground.

Dunstanburgh Castle from the hill. Click the image to enlarge

Turner would have needed quite a close view for details he recorded on his sketch, like the decorative line of stonework above the entrance arch of the castle gateway. From this viewpoint, the Lilburn Tower does appear closer to the main gateway, but it has lost the height it had when seen from the high distant viewpoint, as it dips behind the brow the gateway stands on. Turner’s sketchbook drawing is very accurate in many respects, but it does seem to be a composite with a bit of invention.

Dunstanburgh Castle: Rocks in the Foreground, 1797-8, Tate D01114. Photo: © Tate, London 2012. Click the image to enlarge

In his sketchbook drawing, Turner was composing a fairly straightforward view of Dunstanburgh. However, his thinking soon changed. In a preparatory sketch, Turner concentrated on the idea of a wild and dramatic coast, with jagged rocks quite unlike the actual flat-topped rocks at Dunstanburgh.

JMW Turner (1775-1851), ‘Dunstanburgh Castle’, about 1798-1800, G5656. Click the image to enlarge

The essentials of the Laing’s watercolour are present in Turner’s sketchbook drawing, although at first sight the two views look quite different. Turner just moved the double gateway towers and shortened the castle walls on the right for the watercolour. The outlines of shadows on the cliff and the lines of the castle walls follow pencil marks on the sketch.

Turner increased the drama and energy of the watercolour view by upsetting the compositional balance, placing the castle off-centre. However, he didn’t take this to extremes – the double towers of the gateway are only just to the right of the picture centre.

Detail of ‘Dunstanburgh Castle’ by JMW Turner. Click the image to enlarge

Poetry was very important to Turner, and it influenced the way he chose to represent Dunstanburgh. In 1798, Turner exhibited an oil painting of Dunstanburgh, very similar to the view in the Laing’s watercolour, but representing the castle at dawn. To accompany the picture, he chose lines of verse praising the sun (the sun was an obsession of Turner’s) from James Thompson’s poem Seasons. They describe:

The precipice abrupt…Rude ruins glitter; and the briny deep Seen from some pointed promontory’s top,

These lines of poetry are most probably the reason for the sharp cliff – a ‘precipice abrupt’ – in Turner’s watercolour. They are probably also why he showed a pool of light on the Lilburn Tower – to make the ‘rude ruins glitter’, in contrast to the shadow over the rest of the castle.

This kind of intellectual and imaginative association gave landscape views value in the eyes of critics and collectors. Artists were expected to use their creative powers, not just copy nature. Turner himself stated the importance of imagination in his work:

…it is necessary to mark the greater from the lesser truth: … namely that which addresses itself to the imagination from that which is solely addressed to the Eye.

The sombre effect of the shading over the massive gateway and cliff in the watercolour, together with the castle ruins, jagged rocks and rough sea, were all in keeping with the Sublime style of painting. This style emphasised the awe-inspiring aspects of wild nature, and often included evidence of how even the most mighty achievements of mankind were no match for the power of natural forces.

Dunstanburgh Castle in sun and shade. Click the image to enlarge

Turner’s imagination was founded on his knowledge of nature. When he was at Dunstanburgh, he may have seen something like the view in this photo, when clouds have briefly created pools of light and shade over the castle.

Turner had a lifelong interest in the effects of light in landscape, and the Laing’s watercolour illustrates one aspect of how he expressed this in the early part of his career.

Turner painted Dunstanburgh several times during his career, though he made only one visit. (All Turner’s Dunstanburgh pictures can be seen here.)

Of course, blog images can’t do justice to Turner’s watercolour. However, you can see the Laing’s picture of Dunstanburgh in Watercolour Stars, October 21st to November 25th 2012, along with many other outstanding pictures from the Laing’s collection.

********************************************

Some Turner books and web pages

Eric Shanes discusses Turner’s imaginative approach to art in ‘A Turner Biography’ here.

There are some details on Romantic and Sublime landscape painting here and here.

David Hill, Turner in the North: A Tour Through Derbyshire, Yorkshire, Durham, Northumberland….in the Year 1797 (1996)

Eric Shanes, Turner’s watercolour explorations, Tate exhibition catalogue (1997)

Andrew Wilton, Turner and the Sublime, British Museum Publications (1980)