Was Girtin a better watercolourist than JMW Turner? Turner himself seemed to say so – after his friend’s early death, Turner remarked,

If Tom Girtin had lived, I should have starved.

He was exaggerating wildly, of course, but Turner’s words show his admiration for the impressive effects Girtin achieved. The Laing’s watercolour of Morpeth Bridge shows how Girtin was able to transform an ordinary view into a scene filled with light, weather and drama. His innovative techniques and creation of atmospheric space put Girtin at the forefront of developments that subsequently made British watercolours famous.

‘Morpeth Bridge’ 1802, by Thomas Girtin (1775-1802). Watercolour, ink, pencil on paper, 52.9 cm x 32.1 cm, Laing Art Gallery, purchased 1979 with grant-aid from the Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Fund, the Art Fund and the Wigham Richardson Bequest. D4812. CLICK to enlarge.

Girtin visited Morpeth in 1800 during a sketching tour of the north of England. He painted the Laing’s watercolour probably two years later. His picture shows the ancient stone bridge over the River Wansbeck, on the edge of the old town. Sunshine picks out the most important buildings – the bell-tower of the 13th-century Chapel of All Saints, on the left, and the later part of the Chapel, next to the bridge (together, they were known as Bridge Chantry). Although there’s no great cathedral or castle, the view would have had interest for collectors at the time, as the pioneering naturalist William Turner (1508-1568) attended the school in the old Chapel (it was a multi-purpose building – the chaplain also collected the tolls from users of the bridge.)

Old Morpeth Bridge from the river bank. CLICK image to enlarge.

I snapped this view from the top of the bank, peering between trees. At the time of Girtin’s visit, the view may well have been much more open, without those troublesome trees. The old bridge is now a footbridge (Chantry Footbridge) – the arches were removed about 30 years after Girtin visited, and a walkway added later. (It was damaged in the September floods this year, but has now been stabilized.) Trees now obscure much of the Chapel building behind the bridge, but it’s easier to see if you enlarge the photo. The fisherman standing in the river shows that it’s still (usually) as shallow as Girtin painted it. (The weir on the left was moved to this position about 29 years after Girtin’s visit, to enable water to be channelled to a new mill – the tall building on the far left.)

Distant view of old Morpeth Bridge from the river bank. CLICK image to enlarge.

This more distant viewpoint shows that Girtin’s watercolour view of the river and both banks was feasible. Since Girtin’s day, however, new buildings have been put up, including the church with a spire, and two mills on the left.

Chapel and river, detail of ‘Morpeth Bridge’ 1802, by Thomas Girtin. CLICK image to enlarge.

Girtin’s technique was very different to that of earlier artists, who had used blocks of grey for shaded areas, overlaid with thin, flat colour. When painting the buildings in this view, Girtin constantly varied the colour to recreate the effect of light through cloud on the stone. The attractively spontaneous quality of his painting method is evident in the blue brushstrokes dashed in around the bell-tower – they’re there to make the pale colour of the stone stand out more brightly. Paradoxically, Girtin’s picture is full of greys, but they’re complex hues mixed with blues and browns that give a rich and subtle effect against the pale gold stone and russet roofs of the buildings.

Sky and river, detail of ‘Morpeth Bridge’ 1802, by Thomas Girtin. CLICK image to enlarge

The sun shines brightly in Girtin’s picture, but it’s actually created just from bare paper, contrasted with the dark clouds. Girtin also initially left bare paper for the smoke and the tiny figures on the bridge, adding in little touches of colour to these areas after painting the sky.

Chapel and river, detail of ‘Morpeth Bridge’ 1802, by Thomas Girtin. CLICK image to enlarge

By layering transparent washes in shades of blue, grey and brown, Girtin was able to suggest the depth and transparency of the water. He created the shimmer of reflections by dragging dryish colour over the rough paper that he preferred to use. For an extra-bright gleam of light (behind the rider), Girtin scored through the paint with a sharp point to the paper below.

‘Morpeth Bridge’ 1802, by Thomas Girtin. CLICK image to enlarge.

Girtin used subtle colours to create harmony throughout his picture. At the same time, the resonant colours combined with light shining through threatening storm clouds create an emotional quality within the landscape.

Girtin greatly admired the pictures of Rembrandt, who composed landscape scenes in light and shade to create drama, while also ensuring a unified and balanced arrangement. As a very young man, Girtin copied Rembrandt prints during sketching evenings at the London home of art enthusiast Dr Thomas Monro. (For discussion of Rembrandt in relation to some of Girtin’s watercolours, see here and here.) The wide vista and weather-filled sky of Morpeth Bridge are features that Girtin also learnt from other Dutch landscape painters, such as Salomon Ruysdael and his nephew Jacob van Ruisdael. Their pictures were admired by many British 18th-century collectors and artists.

Girtin combined the examples of Dutch art with his own observation of landscape. In the later part of his career, he often went to great lengths to record the colours and atmosphere of a scene. The writer of his obituary in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1803 gave the example of a sketch Girtin had painted:

…which was principally coloured on the spot where it was drawn, for he was so uncommonly indefatigable, that, when he had made a sketch of any place, he never wished to quit it until he had given it all the proper tints. This we particularly notice because it was generally supposed he was careless in taking his sketches, when, in fact, he was remarkably accurate in making them, though very careless of them after they were made.

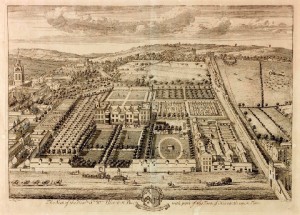

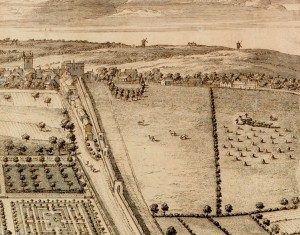

Detail from John Wood’s ‘Plan of Morpeth’, 1826, University of Newcastle, Robinson Library. CLICK image to enlarge

No study for Girtin’s Morpeth Bridge seems to have survived (a small watercolour in the British Museum collection, dated 1800, seems to be an experiment in idealising the scene, and doesn’t have the verifiable detail that’s in the Laing’s watercolour.)

John Wood’s ‘Plan of Morpeth’ of 1826, shows that Girtin was pretty accurate. (The detail illustrated is from Wood’s map on the Tomorrow’s History website.) The buildings of varying heights in front of the old Chapel bell-tower in the watercolour are marked on Wood’s map just below the bridge on the left, next to the river. The Chapel and its extension are marked on the map in dark grey a little above these, and are numbered 6 and 7. On the right side of the map, just below the bridge, there are buildings in a right-angle around a triangle of land – this too corresponds to Girtin’s watercolour. (The weir is shown in its original position on the map – it was moved to allow a new road bridge to be built in 1829-34.)

So, presumably Girtin made an on-the-spot study, carefully painted but carelessly discarded, as the Gentleman’s Magazine, says he often did. It may have been a quite elaborate colour study such as he made for some other pictures.

Girtin’s Morpeth Bridge is part of a change in British watercolour painting towards focusing on light and weather in landscape. Girtin’s mastery of light and the emotional charge it created in his pictures would have particularly impressed his friend JMW Turner.

Thomas Girtin’s watercolour of Morpeth Bridge and another of his paintings will be on display at the Laing Art Gallery from October 20th to November 25th 2012. Two watercolours by JMW Turner will be on show at the same time, so come along and see which you prefer – Turner or Girtin. These pictures will be exhibited together with a watercolour by JR Cozens, whose art Girtin admired, and a scene by Peter de Wint, who continued Girtin’s innovations.

*******************************************************

For further information on Girtin, see

Greg Smith, Thomas Girtin and the Art of Watercolour, Tate Gallery Publications, 2005.