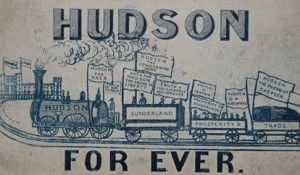

Dan Snow’s History of Railways on BBC 2 recently featured the story of George Hudson (http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b01q7brf/Locomotion_Dan_Snows_History_of_Railways_Episode_2/) Hudson was a man who became loathed by many, especially those who lost their money when the ‘Railway Mania’ bubble burst in in the 1840s. However it was not a black and white situation and whilst his home town of York tried hard to expunge all links to Hudson, had the programme come to Sunderland they would have seen that there was at least one place where he was admired, even loved, long after the exposure of his financial ‘wrong doings’.

Hudson and Sunderland joined forces in 1845 when he became Member of Parliament for Sunderland. He kept his seat in Parliament right up to 1859. He not only developed railways locally, but was responsible for the building of the South Docks enabling Sunderland to compete with other developing ports on the north east coast in the trade that had made it so rich and vibrant by the mid nineteenth century, the coal trade. Hudson himself said at the time that “When all have forsaken me, Sunderland has remained firm to me.”

Monkwearmouth Museum’s star object is Sir Francis Grant’s 1846 painting of Hudson.

Who was Hudson?

Born a farmer’s son in 1800 at Howsham, Yorkshire, Hudson worked his way up from being an apprentice draper aged 15 to partner in the company by the time he was 21. He invested a £30,000 inheritance in the North Midland Railway Company, later becoming a director.

Hudson’s ambition was to turn York into a major railway hub. In 1839 he promoted a railway that connected York to the mainline network for the first time. By 1845 he controlled over 1000 miles of track.

Hudson’s business methods were not always sound. It could take years for a railway to show a profit, so he illegally used money raised for new ventures to pay ‘profits’ to the shareholders of previous ones. This encouraged ongoing investment but when railway expansion slowed in the late 1840s the money dried up, and the ‘Eastern Railway Frauds’ scandal eventually ruined him.

Hudson had become a popular national hero as his enterprises created employment for thousands and he never lost favour in Sunderland. Hudson was sent to debtors’ prison in 1865 but his friends raised money to secure his release. He retired to London and died in 1871.

In 2008 Monkwearmouth Museum staged an exhibition about this complicated character. The star attraction was a letter owned by the National Railway Museum in York (NRM)signed by many prominent people in Sunderland supporting Hudson in 1849 (http://www.nrm.org.uk/~/media/Files/NRM/PDF/archiveslists2012/personal/Introduction%20to%20Petition%20Borough%20of%20Sunderland%20supporting%20George%20Hudson.pdf). The letter was conserved with costs shared by Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums and the NRM. Here is the text from that exhibition.

George Hudson

Railway Napoleon; Capitalist; Humanitarian; Crook . . .

George Hudson has been called all these things, but in Sunderland he is remembered as a hero. George Hudson, MP for Sunderland 1845-1859, was responsible for the development of Sunderland’s railways and building the South Docks. A gutsy and daring entrepreneur, he provided employment for thousands of labourers in Sunderland and the North East region.

The development of railways revolutionised the speed of travel and communications and the growth of towns. It transformed the way wars were fought and empires were run. It was the internet of its day . . . and at the forefront of this wave of change was George Hudson.

Was he a hero or a villain? You be the judge.

George Hudson Comes to Sunderland

George Hudson came to Sunderland in 1845 with a record of achievement in promoting the railways and creating employment, and a firm belief in that the economy should be protected by the Corn Laws, which protected British farmers by placing duties on imported wheat if the prices fell below 80 shillings a quarter although this kept food prices artificially high. What the people of Sunderland wanted most was a successful and prosperous town and this is what Hudson offered them.

With his wife and children in tow, he charmed the traditionally Whig voters of Sunderland into voting Tory. There was speculation that Hudson spent £10,000 charming people to vote for him, and that hundreds of supporters were brought in by train from York. He beat his rival Colonel Perronet Thompson by 627 votes to 497 on 14 August 1845.

‘A more formidable opponent he could not have been . . . with an intangible bribe for every class – the Capitalist would hope for premiums – the smaller fry . . . jobs for their sons in the vast railways . . . the rope, iron, coal and timber merchants all bid for his patronage . . .’

(Richard Cobden, written during the 1845 election campaign)

Entrepreneurial Sunderland

An entrepreneur is a person with a business idea who makes it happen. If the business is a success they make a profit. To start a business they raise money through bank loans and by asking people who have spare money that they want to see grow to buy shares in the project. If the business is a success, people share in the profits based on the size of their investment. If the business fails, people lose their money and can be become bankrupt. In the 19th century you were sent to prison for this.

Sunderland’s economy depended on people risking their money on businesses that could exploit Sunderland’s position on the River Wear and in the Durham coalfield. In the 17th and 18th centuries men like George Lilburne, William Russell and John Thornhill sold coal on from local collieries and made fortunes. In the 18th and 19th centuries thisprofit was used to fund other industries, including shipbuilding, which in turn attracted other maritime industries such as rope and sail cloth making. Sunderland’s position at the mouth of the River Wear allowed it to export coal and import raw materials. Industries such as glass, pottery, lime making and heavy engineering were located here to exploit the easy transport links and availability of coal for steam power.

Railway Mania

The development of the railways in 19th century Britain has been compared to the expansion of the internet. Both were new technologies that promised to change the way we live and work. Both technologies delivered . . . but not without controversy.

The Railway Mania of the 1840s had many parallels to the dot.com mania of the 1990s: many people invested, often more than they could afford, in dramatically new technologies. Some became millionaires, but many investors lost a lot of money. Some losses were due to outright fraud, but most losses resulted from bad business practices, especially poor planning and low initial financing. In the end, both technologies altered the world on a global level and expanded our previously limited horizons. They have had a massive impact on our lives and our sense of who we are.

Election Fever

The 19th century saw fundamental changes in the way British politics were run. The Great Reform Act of 1832 granted seats in the House of Commons to towns like Sunderland that had sprung up or grown massively during the Industrial Revolution. It also increased the number of people entitled to vote from approximately 366,000 to almost 8 million by 1885. Sunderland did not have parliamentary representation of its own until 1832, when the Reform Act allowed the borough to send two representatives to Westminster. Further reforms included the Ballot Act of 1872, which abolished public voting in the hope that secret ballots would make it far more difficult for voters to be bribed or intimidated.

Hudson’s Railways

In 1833, George Hudson entered the new and exciting world of railway investment as the treasurer and largest shareholder of the newly created York Railway Committee. Hudson quickly expanded operations by combining smaller, existing railway lines into larger companies. This included lines such as the York Railway and the North Midland Railway. By 1840, these two companies had become the York and North Midland Railway (YNM). The YNM Railway boasted a 217-mile uninterrupted track from London to York with only a ten-hour travel time.

By 1841, the race to construct a direct route from London to Edinburgh was on. Over the next few years Hudson, by combining railway companies and getting richer in the process, had earned his nickname ‘the Railway King’. By the end of 1848, the face of Britain had changed. In less than 25 years over 5000 miles of railway track had been laid in Britain, and ‘the Railway King’ George Hudson controlled over 1000 of those miles.

South Dock Boost for Sunderland

By the middle of the 19th century Sunderland was fighting competition for the shipment of coal, not only from Tyneside but also from new docks at Seaham Harbour, developed by Lord Londonderry,and Ward Jackson’s new docks at West Hartlepool. In Sunderland ships were unloaded and loaded in the river or along the quaysides. This could only happen when the tide was right. Hedworth Williamson’s North Dock of 1837 was too small and on the wrong side of the river to connect with the railways from most of Durham’s coalfield. A dock on the south side was talked about for many years and Hudson was elected on his promise to build one. A significant part of the capital for the work came from the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway Company. Managed by Hudson’s South Dock Company, the new dock helped to restore and build Sunderland’s share of the market. However, the South Dock Company was overcharged for access to its dock by the rival River Wear Commissioners, and failed to make profits for itself. In 1858 the River Wear Commissioners took control of the dock and went on to expand it, building a second dock in the 1860s.

The Bubble Bursts

The mid-1840s were the beginning of the end for the wild financial speculation of Railway Mania. The 1844 Railway Act controlled the development of the railways, and in 1845 interest rates went up from 3% to 5%. An economic downturn was blamed on the railways for absorbing too much of the country’s wealth – about half of Britain’s investment was going into railways, of which a third was by Hudson. Whatever the cause, the result was less investment in the railways. This exposed Hudson’s ‘sharp practice’ of paying out dividends to shareholders from the capital raised for projects, rather than from revenue income raised by the business (which was necessary because new railways weren’t always immediately profitable). This came to light in 1848, and by the end of 1849 the game was up. Many people who had invested their savings lost out. They appear to have known what Hudson was doing and did not mind when the shares were paying out at 10%. When it all collapsed, however, they wanted a scapegoat, and Hudson was pursued for many years by his companies’ shareholders, to whom he owed £16,000.

Sunderland Remains Firm

Hudson did not shrink from public life. He continued to believe in himself and found that his support in Sunderland remained as strong as it had done since he was elected MP. This was because he was delivering what he promised: a new dock, linked to the new railway network, that could improve the port’s ability to ship coal. In the South Dock’s first eight years of operation, coal exports from Sunderland increased by 56%. Hudson remained Sunderland’s MP until 1859. While Parliament was in session he could not be declared bankrupt, but when it was on holiday he had to leave the country to avoid his creditors. This meant that he could not always be a good MP for the town. Eventually, because of this, he lost his seat and parted company with Sunderland. However, his transformation of the local and regional economy meant that he remained a hero in the town. The South Dock was renamed the Hudson Dock after his death.

Hero or Villain?

Hudson was not a simple character, and many have questioned his methods and even his honesty. However, he could be a generous man who worked incredibly hard for what he believed in, and he was passionate about building and promoting railways. He unleashed the potential of Britain’s industry and trade by creating a transport system second to none in the world at the time. What is left of those railways is still a crucial element of our transport network. And although Sunderland’s economy has changed beyond recognition since Hudson’s day, the docks still exist and run at a profit, albeit with very different cargos.