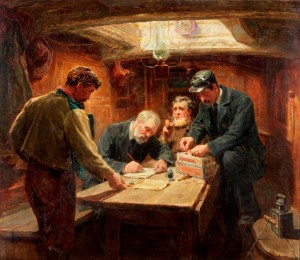

I’ve sometimes heard that the Geordie phrase ‘gan yem’ for ‘go home’ has Viking connections, and it certainly sounds like the Danish equivalent, ‘gå hjem’. Viking rule was established in Northumbria in the 9th century (ruling through a puppet king). Their leader was Guthrum, King of the Danes. He’s shown here in his tent, leaning back with a pretty girl’s head on his shoulder. The picture Guthrum appears in is Daniel Maclise’s Alfred the Saxon King (Disguised as a Minstrel) in the Tent of Guthrum the Dane (1852), in the Laing Art Gallery collection.

I’ve sometimes heard that the Geordie phrase ‘gan yem’ for ‘go home’ has Viking connections, and it certainly sounds like the Danish equivalent, ‘gå hjem’. Viking rule was established in Northumbria in the 9th century (ruling through a puppet king). Their leader was Guthrum, King of the Danes. He’s shown here in his tent, leaning back with a pretty girl’s head on his shoulder. The picture Guthrum appears in is Daniel Maclise’s Alfred the Saxon King (Disguised as a Minstrel) in the Tent of Guthrum the Dane (1852), in the Laing Art Gallery collection.

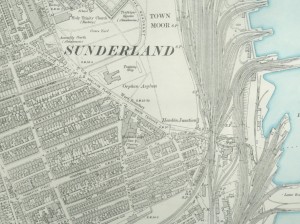

Northumbria was once part of Viking-controlled Danelaw, which covered roughly what’s now the northern areas of England, the East Midlands and East Anglia. In 878, this division was formalised in an agreement between Guthrum and King Alfred of Wessex, who ruled the southern part of England. The story behind Maclise’s picture says quite a lot about national identity and also about migration – in the brutal form of invasion.

Northumbria was once part of Viking-controlled Danelaw, which covered roughly what’s now the northern areas of England, the East Midlands and East Anglia. In 878, this division was formalised in an agreement between Guthrum and King Alfred of Wessex, who ruled the southern part of England. The story behind Maclise’s picture says quite a lot about national identity and also about migration – in the brutal form of invasion.

It looks like there’s a great party going on in Maclise’s picture. People are laughing and singing. All the colours are bright and attractive, and pretty blossom hangs over the tent. But this is a war party, and there are weapons scattered around.

Maclise has shown King Alfred disguised as a wandering harp-player, spying on the Danes (he’s looking super suspicious in the picture). This story was part of the heroic myth of King Alfred. Actually, it would have been fantastically foolhardy for a king because of the risk of capture. Alfred has been regarded as a great English king for his leadership in war and peace. However, Alfred’s heritage was Saxon, from earlier invasions by Germanic tribes.

Maclise has shown King Alfred disguised as a wandering harp-player, spying on the Danes (he’s looking super suspicious in the picture). This story was part of the heroic myth of King Alfred. Actually, it would have been fantastically foolhardy for a king because of the risk of capture. Alfred has been regarded as a great English king for his leadership in war and peace. However, Alfred’s heritage was Saxon, from earlier invasions by Germanic tribes.

Viking settlement in Northumbria was not peaceful. The monks of Lindisfarne were the earliest victims of the Viking invasions of England, with a raid in 793. Around 80 years later, the monks fled with their holy relics and books, including the Lindsfarne Gospels, eventually settling at Durham (the Gospels will be returning to Durham for an historic exhibition at Durham Library from 1 July to 30 September 2013 – more details here).

Those strong Viking genes will now be part of the make-up of some of the population of the North East. They’re mixed with Celtic and Anglo-Saxon genes, plus the genetic heritage of people who’ve moved to the region since. Scandinavian Viking culture (Vikings came from Norway and Sweden as well as Denmark) was once influential over large areas of what is now England, as well as parts of Scotland, Ireland, and Normandy in France. We can get an inkling of the influence of Viking Norse on the English language in the names of the weekdays from Tuesday through to Friday (named after Viking gods Tyr, Woden, Thor, and Frigg). Viking power reached its peak from 1016 to 1035, when the Danish King Canute (Knut) ruled all of England as well as Denmark and Norway. However, soon after Canute’s death, Saxon kings took power again.

An online article from Sheffield University Linguistics Department points out that there was an earlier divide between regions of England following invasion by Germanic groups – Angles settled in East Anglia and the north, while Saxons occupied more southern areas. The article discusses the way different accents and patterns of speech can act as a focus of identity, as well as other aspects of attitudes to life in northern and southern regions (details here). There has been quite a lot of comment in recent years about economic disparity and perceived cultural divisions between North and South England. Another online article brings together reports of research on these subjects (details here – www.fhv.umb.sk/app/cmsFile.php?disposition=a&ID=17880), including a claim by The Economist magazine in 2012 that the gap between the North and South was growing to the extent that they were almost separate countries (details here). These are complex subjects – maybe you have a view on them?

Do you think the North/ South divide still exists?

What does the heritage of your region and national identity mean to you?

We’d really like to hear your views on this and any issues that interest you in this blog. It is part of a series of blogs linking museum objects to the topics of ‘Migration’, ‘Britishness’ and ‘Culture in an Industrial Region’. Later in the summer, there’ll be a debate on the most popular topics featuring Northumbria University academics, museum staff and the general public. You’re welcome to come along to listen or contribute – details will be posted later. Do let us know what you think!

Here’s some links to more Viking information, in case it’s of interest – Viking Northumbria; Vikings in Britain; Alfred the Great; Vikings in Ireland; Danelaw; Guthrum, Danish king.