Costume collections are typically inundated with women’s clothes and accessories, while menswear remains to be relatively under represented. There could be many reasons for this; men tend to wear their clothes for longer eventually wearing them out and having to throw them away, as opposed to women who seem to replace their clothes more frequently! Regardless of this limitation, the items we do have in our collection are just as beautiful and intricate in their tailoring and design as the women’s wear.

This blog will be the first of a two part look at menswear through the ages and the shapes, styles and trends that dominated the eras.

From 1813 to around 1825, the cut away coat was fashionable for both evening and day wear; however it was gradually replaced by the double breasted tailcoat. This coat, unlike earlier versions, had a low waistline and tails which curved back over the hips and finished a few inches above the back of the knees. It is clear that men were attempting to create the same silhouette as women of the time with a narrow waist and wide hips. This shape was achieved mainly in two ways: the bodice was tapered to a tight waist and the tails cut separately from the bodice, were pleated and flared out over the hips. This narrow waist was further accentuated, sometimes by the use of corsets or back laced waistcoats!

After 1825 the frock-coat became the fashion for daywear and tail coats were retained for evening dress.

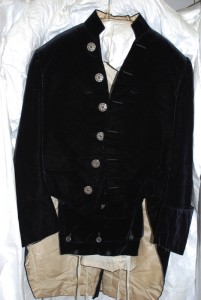

This frock-coat was generally single breasted with a full skirt and large buttons from the neck to the waist. Like the tailcoat, the frock-coat was fitted at the waist and the skirt flared just above the knee.Breeches were no longer worn for everyday wear, but were saved for court dress. In their place, pantaloons were worn by all classes throughout Europe. They varied considerably in length and cut according to the wearer, however for evening dress they normally reached about two inches above the ankle and for daywear they were usually full length and strapped under the foot in the same way that ski pants are today.

Neck wear was the most important feature of male costume in the Romantic period and was considered to be an art form. There were many different ways of tying a cravat and there was even a step by step guide published by H, Le Blanc in 1828 which demonstrates the importance of this accessory in male fashion.

In the 1850s and 1860s male costume showed all the characteristics which would dominate for the rest of the nineteenth century. The two basic coat forms survived; the frock coat for day wear and the tail coat for evening dress.

The frock coat was no longer nipped in at the waist and fell to just above the knee. This coat changed very little until the First World War, however it was to be replaced by other types of coat for less formal occasions, such as the morning-coat which developed from the cut away riding coat of the 1840s.

Knee breeches were now totally obsolete and the peg top trousers of the previous decade also disappeared. The tubular trousers which survive today were left. They were generally a little tighter than those worn in the twentieth century and were neither creased nor fitter with turn ups. Rather than being strapped under the foot, these trousers were now longer and covered the shoes.

By the end of the century the menswear had lost nearly all its colour. Sobriety was the ideal characteristic of the gentleman’s costume which was to be of excellent cloth and cut but in dark, or muted colours. The top hat remained an essential item in every man’s wardrobe until the First World War. It was so popular that is was worn by all classes and professions.

Stay tuned for the final instalment of menswear from 1900-1980!