Biba was one of the most popular fashion stores in London by the end of its life in 1975. It originally started out as a mail order service created by the Polish-born Barbara Hulanicki with the help of her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon. Biba’s postal boutique had its first significant success in May 1964 when it offered a pink gingham dress to readers of the Daily Mirror. The dress had celebrity appeal, as a similar dress had been worn by Brigitte Bardot. By the morning after the dress was advertised in the Daily Mirror, it had received over 4,000 orders. Eventually, some 17,000 outfits were sold.

The first store was opened in September 1964 on Abingdon Road in Kensington. As the Biba style of tight cut skinny sleeves, earthy colours and its signature logo became more and more recognisable, the more and more people wanted to be seen in it. The second store in Kensington Church Street opened in 1965 and series of a mail-order catalogues followed in 1968,which allowed customers to buy Biba and the style that came with it, without having to come toLondon. The next move, in 1969, was to Kensington High Street into a store which previously sold carpet. Again the shop was a unique mix of Art Nouveau decor and Rock and Roll decadence.

In 1974, the store moved to the seven-storey Derry & Toms department store know as the ‘Big Biba’, which immediately attracted up to a million customers weekly, making it one of the most visited tourist attractions in London. There were different departments, and each floor had its own theme, such as a children’s floor, a floor for men, a book store, a food market, and a “home” floor which sold items such as wallpaper, paint, cutlery, soft furnishings and even statues. Each department had its own logo or sign, which was based on the Biba logo and had a picture describing the department; these were designed by Kasia Charko.

The store had an Art Deco-interior reminiscent of the Golden Age of Hollywood interspersed with non-traditional displays, such as a giant Snoopy and his doghouse in the children’s department, where merchandise based on the Peanuts comic strip was sold. The Biba Food Hall was also designed ingeniously, each section being aimed at one particular kind of product. A unit made to look like a dog displayed dog food; a huge baked beans tin displayed tins of baked beans and so on. The new “Big Biba” was also home to “The Rainbow Restaurant”, which was located on the fifth floor of the department store and would become a major hang-out for rock stars, but which wasn’t solely the reserved of the elite.

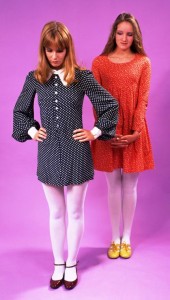

The Biba look appealed to mostly teenagers or twenty year old women. The employees were from the same demographic; among them at one point was a young Anna Wintour, later the editor of Vogue. The Biba look consisted of what Hulanicki called “Auntie Colours” – blackish mulberries, blueberries, rusts and plums. Biba smocks were uncomfortable and itchy, and stopped women’s arms from bending – something that didn’t prevent customers from buying the clothes. These clothes became the uniform of the era with the added bonus of matching accessories available to purchase with most of the clothing.

Miniskirts were causing a scene of their own, every week they got shorter. Although Mary Quant was the first British designer to show the mini skirt, Biba was responsible for putting it on the high street and as miniskirts were in fashion, everyone needed to be associated with them.

Biba’s second store inLondon, the Kensington Church Street boutique, looked like an old apothecary on the outside with an interior that was dark and boudoir like where the clothes were hung up on old fashioned coat racks.

The clothes in the beginning of Biba’s life were extremely affordable and reflected the sentiments of the fashion conscious teenagers of that era, with soft fabrics that were form fitting, very stylish and also extremely comfortable. At the time, Biba used bright colours like blue’s, gold’s and silvers in flouncy chiffons with whirls of muted psychedelic colours and bright boas. Many different kinds of fabric were used including satin, crepe, chiffon, metallic, a fabric that looked like soft felt (which had not been seen before). Biba also had dresses with sleeves that covered most of the hand with thumb holes.

Later in 1969 when Biba moved to its first upscale store on the north side of Kensington High Street, across from where they would later open up their department store, there was a radical change in that the clothes became more expensive and the styles of clothing appeared to be designed for more sophisticated and richer young women in their 20s. The Kensington High Street store also lost the cozy boudoir look of its predecessor, which had been so appealing to its teenage customers, and took on the more sophisticated look of the upscale Kensington/Knightsbridge designer stores.

After some years of severe financial difficulties, Dorothy Perkins and Dennis Day bought 75% of Biba. This led to the formation of Biba Ltd, which meant that the brand and the store could now be properly financed. However, after disagreements with the Board over creative control, Hulanicki left the company and shortly afterwards in 1975, Biba was closed by the British Land Company. There have been various attempts to re-launch the brand but few have been successful until the recent Topshop revival of the brand for which Hulanicki designed a capsule collection. Once again Biba is being enjoyed and appreciated by young women and teenagers around the country.