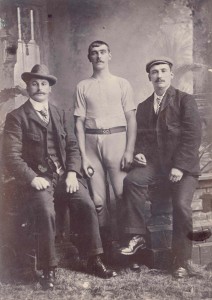

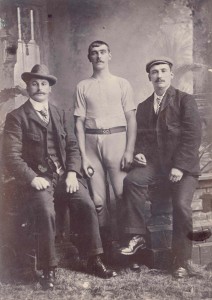

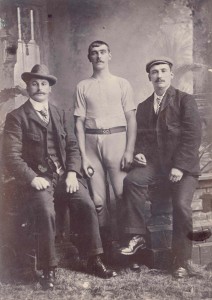

Potshare bowler with his handlers. Stripping to your underwear seems to have been the norm for bowling contests.

We are just coming to the end of ‘Home and Away’, a Heritage Lottery funded exhibition and project looking at the history of North East Sport and the modern Olympics. One of the aims of Home and Away was to provide opportunities for people to learn about, and have a go at, historic sports including some that have now disappeared such as Potshare Bowling.

Potshare bowling was a hugely popular sport in the North East of England right through the 19th century. It was played mostly by coal miners and only in the North East of England. Thousands of people would travel from all over the area to watch and bet on the matches. (1) As with rowing and other prominent sports of the time, gambling was an important factor in its popularity.

The aim was to throw a stone ball over a course, nominally ‘the mile’. ‘The mile’ varied in distance depending on where the match was taking place but on the Town Moor in Newcastle it was roughly 875 yards (800 metres). Two men would take it in turns to bowl with the first one to cross the finishing line being the winner. It was a bit like a very simple game of golf without the clubs or the holes. The bowler would be assisted by a man called a ‘trigger’ who would mark where the bowl stopped with a three foot long stick called a ‘trig’. The next throw would then be taken with the bowl being released when the bowler’s feet were astride the trig. Matches also took place on the Town Moor at Newbiggin, Blyth Links, on the sands at Hartlepool, and, it appears, on back roads and tracks all over the North East.

The origins of the potshare name are unclear. Most probably the ‘share’ part of the name refers to the entrance fees paid into the pot by bowlers when taking part in a knockout handicap competition. The winning bowler would take the lion’s share, or even all, of the ‘pot’ but there might also be cash prizes for other bowlers who performed well. The handicap system encouraged novices to risk their money in the hope that a generous handicap might enable them to beat stronger, more experienced bowlers.

I use the term ‘potshare’ because it has been commonly used in other pieces about bowling. However in a Newcastle Weekly Chronicle article of 2nd August 1884 and a subsequent exchange of letters over the next month, there is no mention of potshare: the sport is just called bowling or, in the vernacular, ‘booling’. All the correspondents have first hand knowledge of booling and had in the past made their own bools, but the word potshare is notable by its absence. My suspicion is that the potshare name came to be used during the last throes of the sport around the time of the First World War and has since stuck.

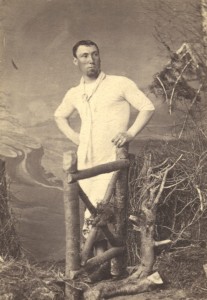

Despite Renforth's natural strength and rowing training he failed to win his only public bowling contest in 1867

The rower James Renforth took part in a contest on Newcastle’s Town Moor for a £4 stake in December 1867. He was up against John King, who was favourite to win at 7 to 4 on. King took the lead in the first throw and beat Renforth by half a throw, perhaps 45 metres.

We were lucky enough to be able to borrow a potshare bowl to display in the exhibition, but very few visitors had heard of the sport and not one uttered the magic words ‘I’ve got one of those at home, would you like it for the museum?’ So when the exhibition was dismantled in January 2013 and the borrowed bowl went back to its owner, the museum was left with no objects connected with this historically significant sport.

From the start we had planned to get a pair of replica bowls made. The scarcity of historic bowls and the lack of knowledge of the sport among our visitors made the production of the potshare bowl replicas increasingly desirable. Research done by me and my colleague Alex Boyd in preparation for the exhibition gave us some parameters for the production of our replicas.

- There was no standard size of bowl. Challenges were made in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle specifying the weight of the bowls to be used. Weights might vary from 5 to 50 ounces but weights between 15 and 30 ounces seem to have been most common.

- The bowls were made from whinstone, more specifically dolerite, a very hard igneous rock used for road chippings and for making dry stone walls. It is not easy to build with and its hardness makes it difficult to work.

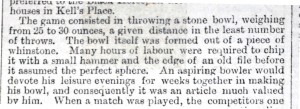

- A fascinating article, ‘NEWCASTLE FIFTY YEARS AGO – XLV BOWLS – BOOLING – “CUDDY RACES” – KITTY-CAT – AND BUCKSTICK, and subsequent correspondence published in the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle in August 1884 describes how bowls – or ‘bools’ in the vernacular – had been made 50 years previously. It is clear from what was written that, by 1884, different methods of manufacture were in use. Consequently, when commissioning the replicas we didn’t feel bound to specify the use of the slow and laborious process described below.

“Men made their own bools out of whinstone by the aid of a small hammer and an old file. Afterwards the bool was submitted to a grinding process in a hole made in hard freestone (sandstone). The bool in course of grinding shaped the matrix. The operation was a slow and long one. ………… This resulted in mysterious round holes with concave cavities sunk into hard freestones about the stone fences and sides of houses that are frequently to be seen in and around pit villages.”

I found a source of whinstone fairly readily at Hanson Aggregates’ Keepershield Quarry, Humshaugh but soon discovered that the quarry mostly produced stone chippings for road building. The end product was created by first blasting the rock and then crushing it to size. There was no equipment on site to cut neat blocks of stone ready for carving, because whinstone is rarely carved. Nonetheless, after blasting but before the rock was crushed, it seemed it ought to be possible to select rough pieces of stone of about the correct size.

Buoyed up by the knowledge that I could get hold of the stone, I searched for a stonemasonry firm that would be willing to take on the job. David France Stonemasonry Ltd of Darlington were used to making ornamental stone balls, but unsurprisingly, given my experience at Keepershield Quarry, they didn’t work with whinstone. David France, a stone mason himself and the boss of the firm, was not sure how difficult it would be to carve a bowl from whin, nor how long it might take. Despite that uncertainty he was willing to give it a go, so we were able to proceed.

I worked out the approximate diameter of bowl we would want to represent the mid – range of weights used in most contests.

Density (P) = mass/volume (grams/cubic centimetre)

Volume (V) of a sphere = 4/3πr3

I weighed a small whinstone pebble I had picked up on the Northumberland Coast. It weighed 325 gms.

Measuring volume by displacement - Measuring jug with whinstone pebble

Using a displacement method and a laboratory measuring jug half full of water I found that the volume of the pebble was approx 120 cc (cubic centimetres).

Measuring volume by displacement - Measuring jug with whinstone pebble and displaced water.

The approximate density could then be calculated.

325 ÷ 120 = 2.708 gms/cc.

A 25 oz bowl is a 708.75 gm bowl

A 25 oz whinstone bowl ought therefore to have a volume of 262 cc

The volume of a sphere is 4/3πr3 (where r is the radius)

For 25 oz: 262 = 4/3πr3 r = 3.97 cm

d (diameter) = 7.94 cm

Looking at old photographs of bowlers that would seem to be about right, although I’m sure many of them would have had hands like shovels so it is not always easy to judge!

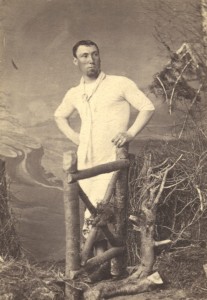

Potshare bowler holding his bowl

Now I knew the approximate diameter of ball we wanted to make, David France was able to tell me what size of rock would be needed in order to make it. The pieces of stone needed to be approximately 20 cm x 15 cm x 15 cm. David also told me that the stone would be prone to fracture as a result of the blasting. He suggested that I collect as many pieces of whin as I could to allow for the discarding of stone that had hidden fractures.

Quarry manager Peter Scott selecting pieces of whinstone

I drove out to Keepershield Quarry where Peter Scott, the manager, took me to the pile of blasted rock and help me select six likely pieces of stone. My assumption is that, in the past, pitmen made their bowls from whin dug or blasted out as waste material during coal mining operations, so their raw material was probably acquired for nothing. Peter kindly supplied our stone under the same conditions!

Whinstone picked off the pile after blasting.

Here’s how the bowls were made by the stonemason:

A diamond core drill being used to cut a cylinder of whinstone

A diamond core drill was used to cut out a cylinder a little greater in diameter than the final bowl.

Whinstone cylinder and the rock from which it was cut

The cylinder was then reduced in size with a saw to create a cylinder of the same diameter as the final bowl.

Whinstone cylinder with diameter reducing process under way.

The whinstone cylinder ready for carving

Finally the cylinder was carved into a ball by the stonemason using a mallet and chisel. Masons usually work wearing safety glasses but in this case the flying chips of whin were so hard and sharp that the mason had to wear a full face mask!

Half a bowl carved

The (wet) finished bowl

The finished bowls had a diameter of 8 cm, and weighed 845 gms (approximately 30 ounces). The 30 oz weight is towards the upper end of the normal range but 25 to 30 ounces was a typical weight of bowl for contests in the 1830s and 1840s.

Extract from the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle of 2nd August 1884 describing how bowls had been made in the 1830s and 1840s.

Replica potshare bowl TWCMS : 2013.498.1

Completed bowl with fracture. The fracture was only revealed near the end of the process so David France kindly supplied it as an extra on top of the matched pair. This bowl is now in a North East Sport loans box and will go out for use as a handling object in schools

They are now part of the museum collection – well recorded as 2013 replicas to avoid any confusion in the future!

As ever, some questions remain:

When was the term ‘potshare’ first used as a name for this very particular form of bowling?

Is there material evidence surviving of bowl making in the pit villages of Northumberland and Durham? This would take the form of mysterious ‘concave cavities’ in sandstone walls, or the sandstone walls of houses, created by grinding a roughly shaped whinstone bowl against the sandstone.

Reference.

1. ‘Potshare bowling’ in the mining communities of east Northumberland 1800 – 1914. by Alan Metcalfe. P29 – 44 in “Sport and the Working Class in modern Britain”, edited by Richard Holt. Manchester University Press 1990. Alan Metcalfe’s paper was used extensively in the preparation of this blog.