Mermaids have been part of myth and legend from as early as 2000 BC and the Assyrian goddess, Atargatis. She flung herself into the sea in grief over accidentally killing her mortal lover. She wished to become a fish, but her beauty was so great that it could not be destroyed and she became a half-female half-fish: the first mermaid.

From Atargatis, to the Greek nereids and tritons, to European folklore of mermaids and sirens- mermaids have always been beautiful and dangerous creatures. They were signs of bad luck, or harbingers of watery doom. Now, most of us associate the myth of mermaids with Disney’s Ariel.

But this particular mermaid is as far from that image as possible.

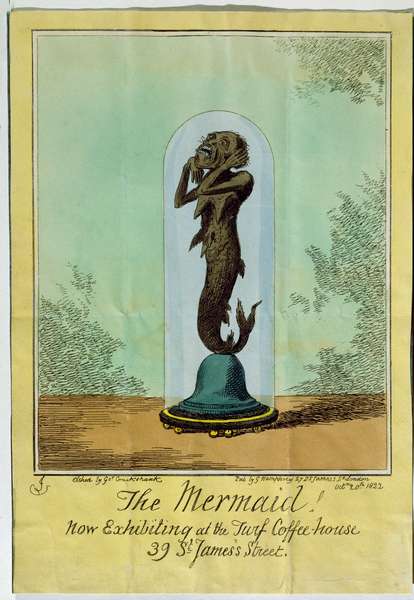

(Copyright Great North Museum: Hancock, TWAM)

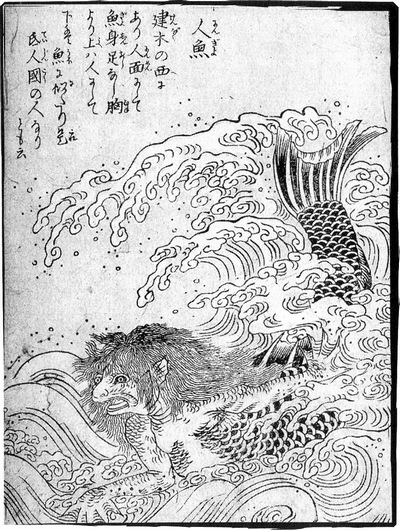

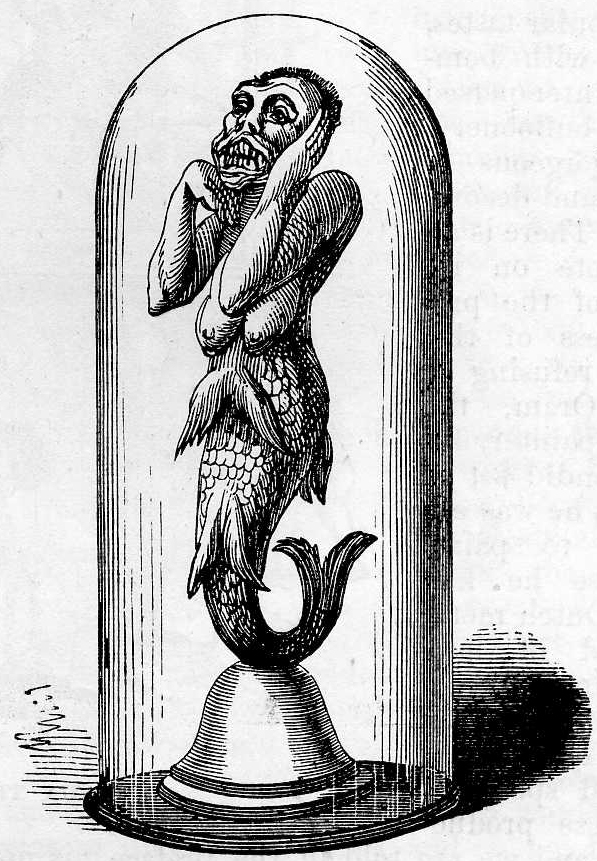

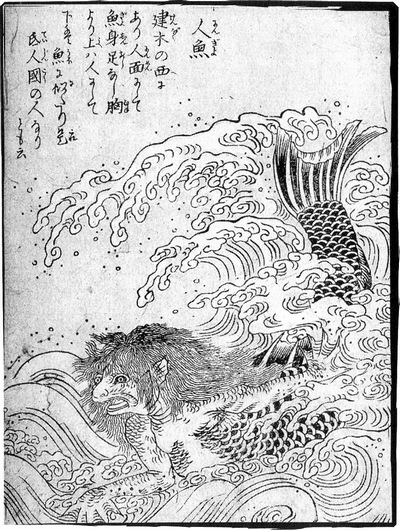

This is our ‘Fiji Merman’… but it is not from Fiji. This name comes from one of the most famous of these specimens. It is actually Japanese; a representation of the Japanese mermaid legend: the ningyo. This legend differs from the common image of the beautiful, human-like upper body and long fish tail. The ningyo is between the size of a baby to that of a large seal. They are hideous to behold, with disfigured fish-like faces, long bony arms, fingers tipped with long claws, and glowing golden scales. Eating their flesh is supposed to give eternal life and youth. But they are powerful and can curse humans who attempt to do them harm.

- Ningyo illustration {{PD-Japan-oldphoto}}

The museum’s specimen is, of course, not a real mermaid. Although there is some variation, these ‘Fiji’ or ‘Feejee’ mermaids are generally a monkey torso attached to a fish tail, often with a ceramic, wooden, or plaster section disguising the juncture of the two. The tradition of making these mermaids began in the Edo Era in Japan (1630-1867), when sideshows including misemono (literally, ‘fake things’) became popular. Many yokai (Japanese supernatural creatures) were manufactured for these shows, and the art form took off. Japanese fishermen began making and selling the mummified ‘mermaids’ to supplement their income.

In the 19th century, shows like sideshows, circuses, freakshows, etc, became popular in America and Europe. Mid-century trade opened between the West and Japan, and trade in these mummified ‘mermaids’ grew.

One particular ‘mermaid’ would make these specimens famous in the West. It was acquired by Captain Eades of the Pickering. He encountered the specimen in Batavia, and completely enamoured of it, sold the ship (of which he owned only 1/8th) to purchase the dried mermaid.

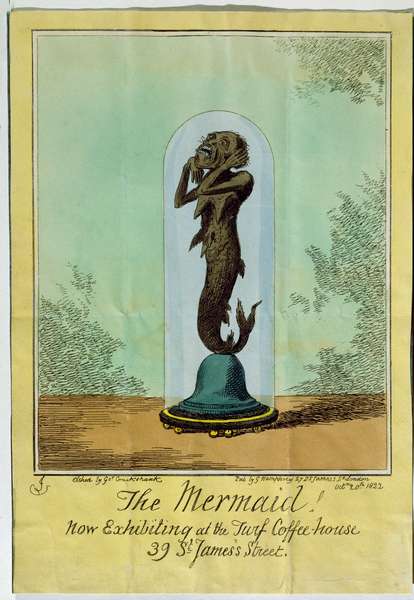

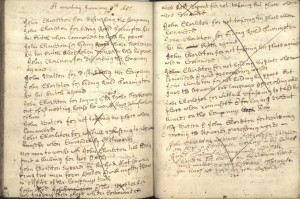

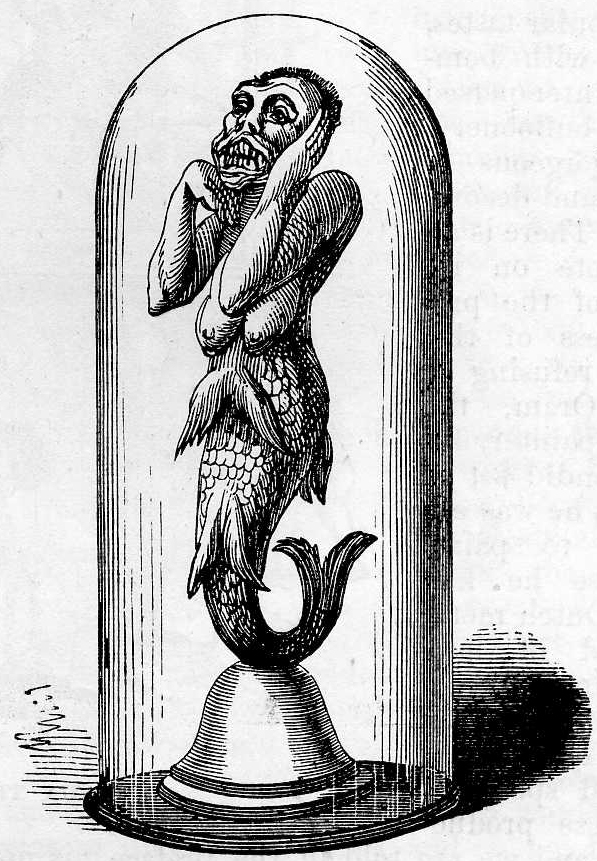

Illustration of Eades' 'mermaid' {{PD-US}} {{PD-OLD}}

September 1822, Eades brought the mermaid to London. William Clift, accomplished biologist and assistant to Sir Everard Home, examined the specimen minutely, and declared not only that it was a fake, but how it was made.

It’s body was 86 centimetres long. The cranium and torso were of a female orangutan, the jaws and teeth of a baboon, and the eyes were artificial. The skin of the face was reconstructed to form the nose, ears, and other features. The bones of lower arms had been sawed through under the skin to shorten them to human proportions and the nails were of horn or quill. The fish was a large salmon, detached just below the head, artfully manipulated to give the impression that a single spine continued through the whole creature.

Fortunately for Eades, Clift and Home were sworn to secrecy before their examination. After several weeks held by confused customs agents, who presumably had never before encountered a mummified mermaid, Eades was able to exhibit his mermaid.

Advertisement for mermaid exhibit, 1822 {{PS-US}}

During the autumn of 1822, Eades’ mermaid was a sensation. It was estimated that every day 300-400 people paid a shilling to see it. The public, less skeptical than scientists, were largely convinced of its authenticity. Other naturalists recruited by Eades to examine the specimen mostly supported this belief.

However, in November 1822, Eades advertised that Sir Everard Home declared the mermaid genuine. This infuriated Home, who decided that this rendered their secrecy agreement void, and ordered Clift to write an article debunking the mermaid.

This was the beginning of the end for Eades’ mermaid. Those scientists who had confirmed its legitimacy were ridiculed for believing in a half-mammal, half-fish. The London public’s interest dwindled away and the exhibit closed in January 1823. The mermaid toured around Britain and Europe with mild success, and within 10 years record of its location was lost.

Eades’ big mistake eventually caught up with him, when the ship’s 7/8ths owner, Stephen Ellery, demanded his money back from the sale of the ship. After a protracted legal battle, Eades was commanded to work off his debt to Ellery, and died at sea still trying to pay it off.

It is at this point in the story we lose the mermaid’s trail for a time, and must travel to America to pick it back up…

In 1842, Mr. Moses Kimball, proprietor of the Boston Museum, informed P.T. Barnum (businessman and entertainer who would go on to found Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus) about a new artefact acquired from a Boston seaman- a mermaid. The Boston seaman told a tale of his father, who had acquired it by selling his ship, and was sentenced to pay back the money for the ship through indentured servitude at sea, eventually dying there with nothing more to his name than this mermaid.

It was Eades’ mermaid!Rediscovered almost 10 years later, thousands of miles away from its last known location. Barnum took the specimen to a naturalist, who immediately pronounced it a manufacture. But Barnum was unconcerned, knowing that he would be able to turn it to his own profit.

He convinced newspapers that a ‘Dr. Griffin’ (really his friend Levi Lyman) from the London Lyceum of Natural History was coming to the United States and bringing a mermaid, caught off the ‘Feejee’ Islands, which he hoped to display to the public. ‘Feejee Mermaid’ (or ‘Fiji’) became become the name by which all of these fabricated mermaid specimens are known. Barnum’s associate, playing the fake Dr. Griffin drummed up interest for the mermaid. Soon, Barnum contacted local papers, telling them that he was trying to persuade Dr. Griffin to allow him to exhibit his Feejee Mermaid, but had failed. He offered each editor the exclusive rights to the drawing of the mermaid he had commission, and each accepted. When the papers were printed, they realized Barnum had given different drawings of the mermaid to each paper. The same day, Barnum distributed 10,000 leaflets advertising the mermaid’s exhibition for 1 week only. The fraudulent Dr. Griffin discussed the mermaid as the missing link between humans and fish in lectures and pamphlets.

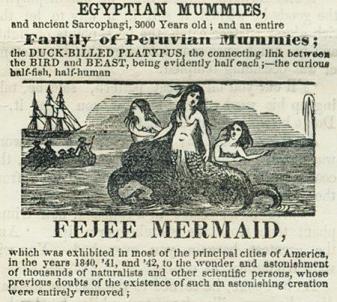

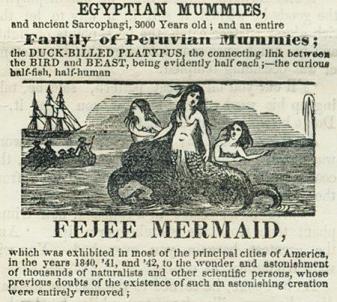

Barnum mermaid advertisement {{PD-US}}

Barnum’s advertising suggested a beautiful womanly figure with a fish tail, but what visitors saw after they had paid their fee left many disappointed and some irate.

By the summer of 1843, New Yorkers were growing bored with the mermaid, so Barnum arranged a tour of the southern states. However, it soon fell apart when, in Charleston, the show got caught between two rival newspapers. It was very popular and drew large crowds, but when it was declared fake, the Charleston public was humiliated and enraged. The mermaid and its manager had to be removed back to New York for safety.

{{PD-US}}

In 1859, Barnum returned the mermaid to Kimball and the Boston Museum. Although Barnum toured with a mermaid again in the 1880s, this was most likely another specimen.

The Boston Museum burnt in early 1880’s, but it was claimed the specimen was rescued, and later donated to Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Ethnology and Archaeology. However, when this specimen was displayed, it was discovered that this “Feejee Mermaid” was not the real fake mermaid, but is another, which differed greatly from the drawings and descriptions of the original ‘Feejee Mermaid’.

So where is the real fake?

Probably destroyed, unfortunately. Most likely, a tinder-dry taxidermy would have burnt with the Boston Museum in the early 1880s, or was destroyed by an unwitting individual ignorant of its worth. No examples yet found in Europe or America have matched the specimen Eades, and then Barnum, displayed.

Our own Fiji Merman was featured in the The Journal this week in an article about the many different magical, mystical, and legendary stories that will be told in the upcoming Magic Worlds exhibition opening March 22 2014.

http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/newcastles-great-north-museum-set-6389046