Ethnographers do not exclusively study historic cultures, or ‘world cultures’ or cultures different from our own. Ethnography simply means ‘study of human cultures’. That is a pretty broad remit.

For me, one of the most exciting aspects of ethnography is engaging with local communities. I love getting people excited about our collections and teaching them about other cultures. Even better is when I get to learn new things from my local communities. One upcoming cultural event being celebrated in the local community really caught my interest- Nowruz.

Nowruz, also called Persian New Year, occurs on the vernal equinox- the exact astronomical beginning of spring. (This year this falls on March 21st.) Nowruz, pronounced “no-rooz,” literally means ‘new day’ in Persian. The festival began thousands of years ago as a celebration in Zoroastrianism (a monotheistic religion founded inPersia approximately 3500 years ago), but Nowruz has been widely celebrated without religious connotations for thousands of years.

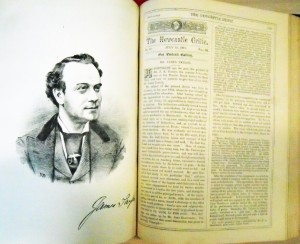

Qajar family celebrating Nowruz. Public domain {{PD-before 1970}}

Although Nowruz originated in Persia, it is celebrated by people all over the world and is a national holiday in 13 countries. Iranians consider Nowruz to be their biggest celebration of the year. It is also significant to the Zoroastrian community as their spiritual New Year, although their traditions differ somewhat from the secular celebrations of Nowruz.

Preparations for Nowruz begin with spring cleaning the home. It is also customary to buy new clothes for the family, and new furniture for the home. Many other varied traditions associated with Nowruz are for predicting the outcome of the new year, or ensuring that it will be a good one. Others symbolize a fresh start.

"Newroz celebration in Istanbul." Photo by Bertil Videt 2006. License: Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 Unported

On the last Wednesday of the year, people traditionally jump over bonfires, shouting “Zardie man az to, sorkhie to as man,” which means “May my pallor be yours and your red glow be mine.” The flames symbolically take away the unpleasant things from the last year.

But jumping over a fire is dangerous, and so many people today light the fire and say the words without jumping.

"Haji Firuz" Photo by Sina S. License: Creative Commons Non-Commercial 2.0 Generic

Traditionally, the character Hajji Firuz, heralds the approach of Nowruz. He wears bright red clothes and his face is blackened.

On the eve of the New Year, families wait together for Tahvil, the exact moment that the new year begins. After Tahvil, the family celebrates. The eldest member distributes sweets, and young children are given coins. Families and neighbours may also exchange gifts.

The most important part of the festivities is the making of the haft-seen table. ‘Haft’ is Persian for ‘seven,’ and ‘seen’ is the letter ‘S’. It means table of the seven things that start with the letter S. Creating this table is a family activity.

"Haft-Sin table, Iran" {{PD-released by author}}

Usually, the family first lays down a special table cloth. Then the table is set with the seven S-items, and other symbolic items. These items depend on the family’s and local tradition.

Haft-seen items:

Senjed (dried oleaster fruit): representing love

Serkeh (vinegar): representing patience and age

Seeb (apples): representing health and beauty

Sir (garlic): representing medicine and healing

Samanu (wheat pudding): representing fertility and a sweet life

Sabzeh (sprouted wheat grass): representing the renewal of nature

Some other traditional items include:

Mirror: representing reflection on the past year

Live goldfish in a bowl: representing life

Coloured eggs: representing fertility

Coins: representing prosperity

An orange in water: representing the Earth

Hyacinth flowers: representing the new spring

Candles: representing light and happiness

National colours: representing patriotism

Often, the table also contains a book. This could be the Avesta (Zoroastrian sacred texts), the Qur’an (Muslim holy book), the Divan-e Hafez (poetry by Hafez, commonly considered the Persian national poet), or another culturally or spiritually significant text.

"Sofre Haft Seen, Laleh Hotel, Tehran." 2007 Photo by Hessam M. Armandehi. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

- Like almost all cultural celebrations, many special foods are prepared for Nowruz. Noodle soup mixed with beans and green vegetables, called Ash, is traditionally served on the first day of the new year, symbolising the possibilities of the new year. Untangling the noodles is said to bring good fortune. Another dish, fish with rice mixed with green herbs, represents the greenness of nature in spring. Other traditional items include special sweets, like naan berengi (rice flour cookies), baqlava (sweetened flaky pastry) and noghl (sugar coated almonds).

-

"Persians (Iranians) in Holland Celebrating Sizdeh-Bedar," April 2011, Photo by Pejman Akbarzadeh / Persian Dutch Network. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

The haft-seen table remains up for thirteen days from the beginning of Nowruz. The thirteenth day is called ‘Sizdah beh dar,’ literally meaning ‘getting rid of the thirteenth’. Traditionally, families pack picnics and go to the park to eat, sing, and dance with other families. It is traditional to bring the sprouted wheatgrass, and to throw it into the grass or into water to symbolize the return of life to nature. This day marks the end of Nowruz.

If you want to wish someone a happy Nowruz, you can say “No-Rooz Mobarak” (translation: Happy New Year) or “Eid-eh Shoma Mobarak” (Happy New Year to you) or “No-Rooz Pirooz” (Wishing you a Prosperous New Year).

An event celebrating Persian New Year will be held on March 26 from 6-9pm, at Culture Lab in Newcastle University. This will include a talk, music, poetry, refreshments, and haft-seen decorations. For more information, visit http://on.fb.me/1j3hxnk.

If you’d like to get involved with Nowruz celebrations or learn more about Iranian heritage, check out the Iranian Heritage Project Facebook page. The Iranian Heritage Project is run by a local organisation, Northern Cultural Projects CIC, who work with the Iranian community documenting and celebrating Iranian heritage in the North East.