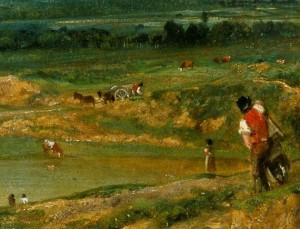

John Constable, Hampstead Heath with the House Called ‘The Salt Box’, © Tate, London 2013

A bright patch of colour – a man wearing a red waistcoat – pulls our eyes out to the far right of this picture, ensuring that we don’t miss the full width of this airy panorama. It shows the view from the high ground of Hampstead Heath, with London behind us. This picture is on show in the Laing’s current exhibition (ticket entry) of naturalistic landscape sketches and paintings – Sketching from Nature, selected from the Tate collection, London. The Tate collection page for this painting can be seen here.

The man in a red waistcoat seems to be tipping up a wheelbarrow. The action has angled his body towards another man, also marked out with a red waistcoat, on the other side of the pond. He’s apparently digging sand to load into a cart (pulled by donkeys, it seems, rather than horses).

John Constable, Hampstead Heath with the House Called ‘The Salt Box’ (detail), © Tate, London 2013

Sand-digging must have been a familiar sight over a lot of Hampstead Heath. As it was common land, villagers had the right to dig sand and gravel, which were variously used for building, road construction, and in glass and iron industries. Constable seems to have thought of the people and animals as a natural and characteristic part of the Heath. He and his patrons may also have seen the labourers as evidence of praise-worthy work, contributing to Britain’s progress and prosperity. However, sand digging over the next 50 years had severe consequences for the Heath. In 1871, The Illustrated London News recorded that:

The whole space on the summit of the hill…has been ruthlessly dug up for gravel and sand…leaving a dreary, desert prospect of hideous pits and shapeless heaps…Holes are scooped out close to the high road thirty feet or forty feet deep…

The Heath was taken over by the Metropolitan Board of Works, and digging banned (there are some details of the Heath’s history here and here.)

At the time of Constable’s picture, Hampstead was still a village, with the advantage of being within reasonably easy reach of the artist’s London house. It was an idyllic spot, and sand digging had not yet noticeably damaged the landscape. Constable rented a house for the summer of 1819 and again in following years, until he moved there permanently in 1827. He described the Heath’s appeal in a letter:

I am three miles from door to door – can have a message in an hour – & I can always get away from idle callers – and above all see nature – & unite a town & country life.

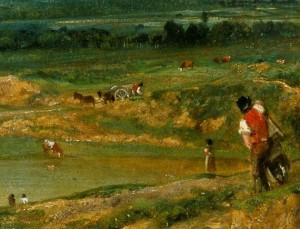

John Constable, Hampstead Heath with the House Called ‘The Salt Box’ (detail), © Tate, London 2013

This wider detail of the right side of the painting features Branch Hill Pond. Constable has depicted a lush green landscape beyond the Heath, creating a subtle progression to the bluish tints of the distant hills. At the bottom of the scene, there’s a narrow band of shadow created by a cloud overhead. Sun shines on the clouds from a westerly direction, and the clouds break up the light into patches on sunshine over the ground.

For Constable, the sky was a fundamentally important part of naturalistic landscape painting. In a letter to his friend Archdeacon Fisher, in 1821, Constable wrote:

That landscape painter who does not make skies a very material part of his composition neglects to avail himself of one of his greatest aids. The sky is the source of light in nature and governs everything

As Constable was living on the Heath, he was easily able to take his easel, canvas and paints outside. Though of fairly modest size, it’s still quite large for an outdoor picture. Constable’s careful observation of nature in this painting was admired by his friend and fellow artist C.R. Leslie:

Constable’s art was never more perfect…as at this period of his life…The sky is of the blue of an English summer day… The distance is of a deep blue, and the near trees and grass of the freshest green; for Constable could never consent to parch up the verdure of nature to obtain warmth. These tints are balanced by a very little warm colour… Yet I know no picture in which the mid-day heat of Midsummer is so admirably expressed; and were not the eye refreshed by the shade thrown over a great part of the foreground by some young trees, that border the road, and the cool blue of water near it, one would wish, in looking at it, for a parasol…. [It] appears to have been wholly painted in the open air…

John Constable, Hampstead Heath with the House Called ‘The Salt Box’, © Tate, London 2013

Although the scene is naturalistic, Constable has incorporated some structure. The sweeping curve of the road directs our eyes across the picture and round into the distance towards the central house. A line of dark trees leads into the picture on the left, contrasting with the brightly coloured and varied forms of the open vista on the right. The asymmetry creates energy, while the central position of the house helps stabilise the pictorial composition. The junction of the building’s red and white roofs marks a vertical line through the centre of the composition, though this isn’t very apparent because both trees and road extend beyond it. Houses with long sloping roofs, like the pale-coloured roof of this building seems to be, were known as ‘salt box’ houses because of the resemblance to the outline of an old-fashioned box for table salt.

In addition to this outstanding picture, the Laing’s current exhibition gives visitors the chance to see two more of Constable’s Hampstead scenes, including one of his fascinating cloud studies. Other pictures by Constable on display cover a range of his outdoor subjects – his father’s mill at Dedham, the coast at Brighton, a sky study made on a visit to his friend Archdeacon Fisher at Salisbury, a country village in full summer sunshine, and an evening study of lush parkland.

Naturalistic landscape sketches and paintings by JMW Turner are also on show as well as pictures by fellow artists who followed a similar path.