For the past five months I have been exploring, documenting and re-packing the fan collection at Discovery Museum, and as part of the project I was asked to produce a ‘top ten’ list. Unwrapping each of the 157 fans was a different experience each time, some very fragile, some ornate and some very unusual. Each fan told its own unique story.

It has been an exciting collection to research due to its variety. The oldest fan in the collection dates from 1730 and the most recent is from 1962. As well as the large date range it also became clear during my project that there were many specific trends in fans, just like any other fashion accessory. This became more recognisable as my project progressed and the trends were not only identifiable by the materials used but also the size of the fan, and the style of decoration.

It was a hard task to choose just ten from this beautiful collection, but after a lot of deliberation I managed to narrow down my findings, all of which are distinctly different and take you on a journey through the collection.

The oldest fan from my top ten dates from around 1760 – 1770 and is a typical example of a French fan from the Rococo period. The bone fan sticks are highly ornate and have been pierced with the most intricate pattern and then embellished with metal pique detailing. The fan leaf is a cream satin jacquard that has been hand painted and depicts a garden scene. Fans like this were often commissioned by the wealthy to show exaggerated scenes of outdoor pursuits. Although the front of the fan is full of beautiful detail, it was the back of the fan with its floral design that I really loved.

Fans similar to this one were often used as celebration fans to mark royal weddings or family christenings. Some were romantic marriage fans, given to the bride from the groom, and have remained in good condition due to only being used once and then being kept as a keepsake.

It was hard to believe some of the dates of the fans as they were either in very good condition or looked more modern due to their colour or materials.

This example caught my eye immediately with its vibrant yellow feathers and bold painted decoration. However this fan, which was made in China, was a popular style throughout the 19th Century, this particular example dating from 1860.

In complete contrast to this vibrant example is an all black mourning fan of the same date. There are only a few mourning fans in the museums collection, but one stood out to me due to its design. The fan sticks, made from black grosgrain satin, have been fashioned into shapes to replicate feathers. This was a typical style at the time due to the limited availability of feathers. Feather fans were quite rare until the last quarter of the 19th Century. Before then shaped feather fans made from other materials were produced instead.

The fan’s wooden sticks are fastened with a mother of pearl rivet and a metal loop is attached along with a piece of black satin ribbon. I had came across a few late 19th Century fans with metal loops or satin ribbon attached and it made me wonder if this was a style feature or a practical addition. After some research I found that metal loops were typically attached to fans from the beginning of the 19th Century as the number of accessories women carried was increasing. Along with a fan they would also carry a parasol and a purse so the loop and ribbon would enable a lady to carry the fan at ease by slipping the ribbon over her finger or wrist. I like to think that a lady would change the colour of the ribbon to match her outfit or personal taste.

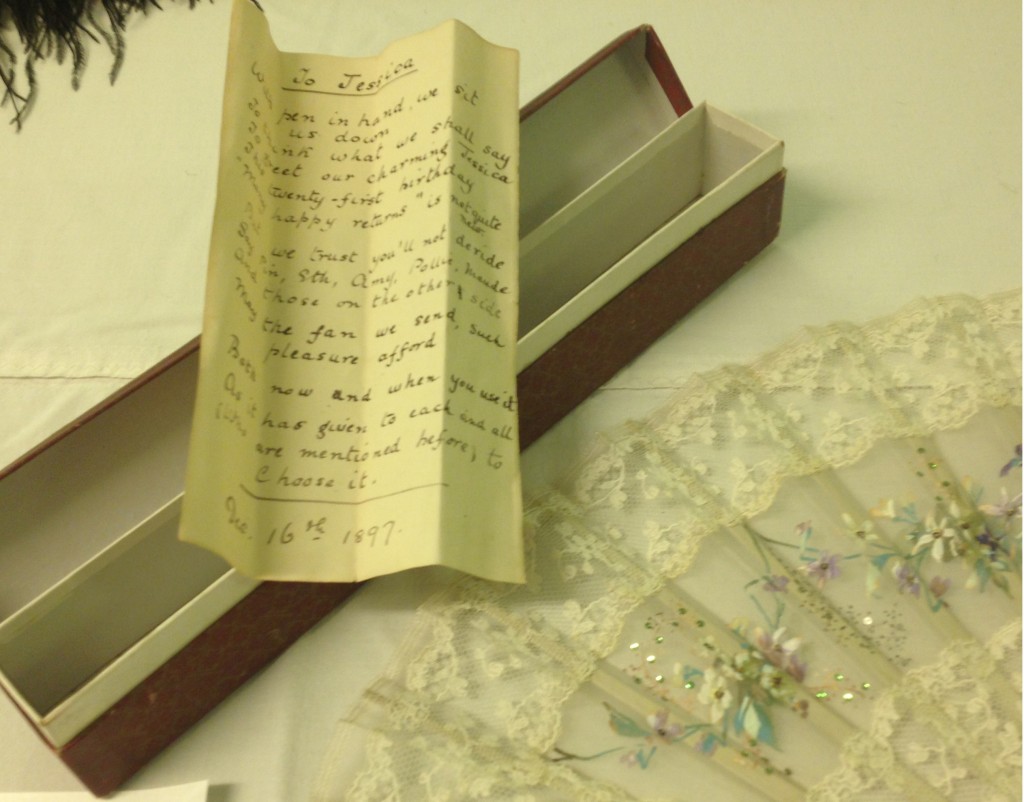

I had spent a lot of time while looking through the collection imagining who would own certain fans and where they would have been used, so there was great excitement in the store on the day that I unpacked a fan and box with a letter enclosed.

The letter, which is dated December 16th 1897, shows that the fan was given as a 21st birthday present, it reads:

To Jessica,

With pen in hand, we sit us down

To think what we shall say

To greet our charming Jessica

This twenty-first birthday

‘Many happy returns’ is not quite new.

But we trust you’ll not deride

Say Pip, Eth, Amy, Pollie, Maude

And those on the other side

May the fan we send such pleasure afford

Both now and when you use it

As it has given to each and all

(Who are mentioned before) to choose it.

Dec, 16th 1897

The fan is in pristine condition considering its age and is very similar to those used at that time by a bride on her wedding day. Bridal fans at the time were typically made of gauze and pieces of lace matching the brides’ wedding gown would be appliquéd to the fan.

Fans were not only used as a decorative accessory, some also had more practical uses. Fans like this one, including a cassolet, which means ‘with rouge for the cheeks’, were seen as early as 1900.

This particular fan dates from 1890. The sticks and guards are made of bone and have been pierced with a delicate design. The cassolet is a very ornate gold plate and is attached to the outer fan guard. The fan leaf is made up of two layers of paper, in silver and blue. The paper has been pierced with small stars letting the silver shine through and glisten in certain lights.

Although very subtle, I believe this could be an early advertising fan. Advertising fans became popular from the 1890s. Shops and restaurants in Paris would often advertise using fans and even later in the 1950s the influential fashion designer Christian Dior used fans to promote his fashion house.

In my next post I will talk about the remaining five fans from my top ten, which also includes my favourite from the whole collection.