In recent months, myself and fellow volunteer Emma have been developing the digital records for Discovery Museum’s fan and sampler collections. In practice this has meant a lot of happy hours spent in the Museum’s costume store working with some interesting and beautiful objects. This blog posts marks the end of the project and also an opportunity to share with you some of the items I’ve been working with – Emma’s first post about the fan collection can be found here.

Myself and Emma in the costume store.

Sampler: A piece of embroidery worked in various stitches as a specimen of skill, typically containing the alphabet and some mottoes. (Oxford Dictionaries Online, 2014)

I was keen to get involved with this project because of a personal interest in sewing and a desire to learn more about the history of samplers. I had always thought of them as decorative objects and in my own family they were typically made to mark a life event such as a birth or marriage. What struck me when working with the collection was just how much the role of samplers changed over the centuries, developing from a practical record into something with both a decorative and educational value. With this in mind I decided to write a potted history of samplers, using some of my favourite examples from the collection.

17th Century sampler, object number TWCMS : D395.

1. My first choice is the oldest sampler in the collection and dates from the first part of the 17th Century (c.1600 – 1630).

The earliest documented reference to a sampler in England is from 1502 and although few survive from this period a number of pattern books are still in existence. Many of these early books included cutwork, or lacework, a technique in which sections of fabric are removed and the remaining material reinforced to create a lace effect. This first sampler contains elements of cut and drawn thread work (a related technique) and an array of stitches, including buttonhole, chain and satin stitch. This particular sampler is an example of whitework, where a base fabric and thread in the same shade are used. Given the fine level of detail this example would undoubtedly have been the work of an experienced adult hand, requiring both patience and skill to complete.

17th Century banded sampler, object Number TWCMS : H6069.

2. This sampler is a later 17th Century example, dated 1683. As with the previous example, this sampler is organised into banded sections that were typical of samplers from this period. However, an earlier form of ‘spot sampler’ (see here) would persist well into the century. Defined by its more random arrangement of motifs, the spot sampler’s form was indicative of their continued use as a practical reference piece during this period. The growing popularity of this banded style therefore marks a development in the function of samplers, which became an increasingly decorative means to showcase the skill of their maker.

In this example the selvedge of the base fabric (the finished edge that stops the material fraying) is clearly visible. It is thought that the long thin shape of these 17th Century samplers was dictated by the maximum loom width used to make the fabric, with the selvedges forming the top and bottom of the work.

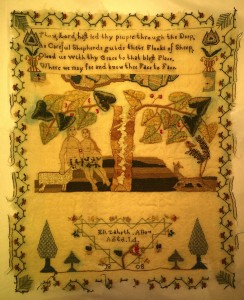

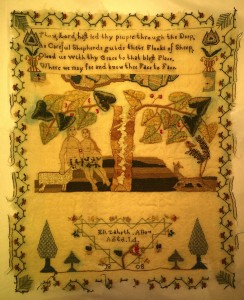

Sampler (1808) by Elizabeth Allon, object number TWCMS : H6769.

3. Jumping forward 100 years, there is a marked shift in the style of this sampler from 1808. The band structure is gone and replaced by a more loosely worked central panel, depicting Adam & Eve, a strawberry border and accompanying verse:

Thou Lord haft led thy people through the Deep,

As careful Shepherds guide their Flocks of Sheep,

Olead us With thy Grace to that blest place,

Where we may see and know thee face to face

Over the course of the 18th Century, samplers became increasingly decorative and it was common for them to be organised around a central image or verse like this. This sampler is also much squarer than its predecessors, a shift that is attributed to a greater tendency to frame the finished work, rather than storing it away for reference.

This sampler was made by Elizabeth Allon and contains a mention of her age as ’14 years’. From the early 1600s there was evidence that samplers had started to play a role in the education of young women and in the 17th C. they became a vehicle to demonstrate a girl’s knowledge in other fields, including religious education. Adam and Eve were among the first biblical figures to appear on samplers and some of the earliest depictions were executed in cutwork on white linen.

A comparable sampler illustrating the biblical story of Susanna and the elders can also be found in the Museum’s collection (Accession number: H6761).

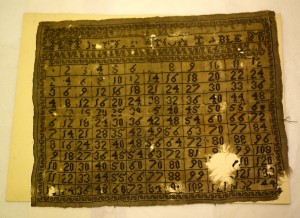

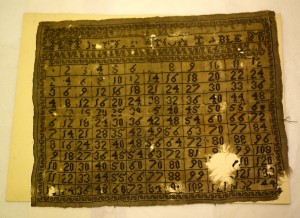

19th century ‘multiplication table’ sampler, object Number TWCMS: 2008.2630.

4. My last selection for this post is a ‘multiplication table’ sampler from the first half of the 19th C. (c.1825 – 1850).

In ‘Johnson and Walker’s A Dictionary of the English Language’ (1828), samplers are summarised as ‘…a piece worked by young girls for improvement’ and this type of multiplication sampler is testament to their continued role in educating young women. Throughout this period other types of educational sampler were also common, including maps and almanacs and these samplers would almost certainly have been completed as a school exercise, rather than at home.

Although this is a relatively simple example, this sampler has been skilfully worked and contains a decorative border and lettering across the top. The figures on this example have also have been filled in correctly, which wasn’t always the case with samplers of this type.

This first post includes some of the earliest samplers in the collection and in part two I will look at some more recent examples which show how the practice developed in to the 20th century. If you would like to find out more about the collection you can search the online catalogue here using the object number (listed below each image) or the simple search term ‘sampler’.

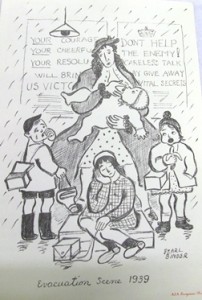

Pearl Binder captures here something of the pathos and sense of uncertainty and displacement caused by evacuation: it is more a detailed sketch or cartoon in its style, rather than some of the other more considered and painterly prints of early Wartime scenes in the Everyman series, and it reflects the candour and also the idiosyncracy of the artist: Pearl Binder was a remarkably versatile artist: described in her Wikipedia entry as a “writer, illustrator, playwright, stained-glass artist, lithographer, sculptor and a champion of the Pearly Kings and Queens”, she also produced fiction and journalism, was involved in the earliest days of British television from the mid 1930s, being a pioneer of children’s television in this country, and created a series of stained-glass windows for the House of Lords. She designed pottery for Wedgwood and costumes for theatre productions, designing a musical based on the historical figure Pocahontas, who fascinated her, for Joan Littlewood at the Theatre Royal Stratford East. She was an inveterate traveller and chronicler of her travels, particularly in Russia and China, illustrated several books and was a superb chronicler of East End life, particularly its Jewish community after the First World War, having moved to Whitechapel in the 1920s from Salford. Astonishingly enough, given her origins as the daughter of a Jewish Russian/Ukranian tailor, she became associated with the higher echelons of British society and political power when she left the East End in 1937 to marry a lawyer, Frederick Elwyn Jones, later Lord Elwyn Jones, who was appointed Lord Chancellor in 1974.

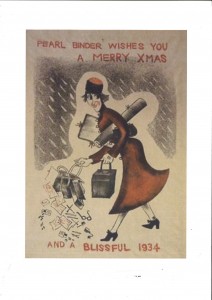

Pearl Binder captures here something of the pathos and sense of uncertainty and displacement caused by evacuation: it is more a detailed sketch or cartoon in its style, rather than some of the other more considered and painterly prints of early Wartime scenes in the Everyman series, and it reflects the candour and also the idiosyncracy of the artist: Pearl Binder was a remarkably versatile artist: described in her Wikipedia entry as a “writer, illustrator, playwright, stained-glass artist, lithographer, sculptor and a champion of the Pearly Kings and Queens”, she also produced fiction and journalism, was involved in the earliest days of British television from the mid 1930s, being a pioneer of children’s television in this country, and created a series of stained-glass windows for the House of Lords. She designed pottery for Wedgwood and costumes for theatre productions, designing a musical based on the historical figure Pocahontas, who fascinated her, for Joan Littlewood at the Theatre Royal Stratford East. She was an inveterate traveller and chronicler of her travels, particularly in Russia and China, illustrated several books and was a superb chronicler of East End life, particularly its Jewish community after the First World War, having moved to Whitechapel in the 1920s from Salford. Astonishingly enough, given her origins as the daughter of a Jewish Russian/Ukranian tailor, she became associated with the higher echelons of British society and political power when she left the East End in 1937 to marry a lawyer, Frederick Elwyn Jones, later Lord Elwyn Jones, who was appointed Lord Chancellor in 1974. Pearl Binder died in 1990 aged 86: what a shame that the work of such a multi-talented and charismatic artistic figure is so rarely discussed or shown today. Someone who does keep her memory alive is her son, poet and rhyme-collector Dan Jones: I am indebted to him for his permission to reproduce the Christmas card from 1934, one of “the litho greetings prints that she continued to produce every Xmas for the next 50 years, come hell or high water…” says Dan, plus the striking photograph of his mother shown above: he tells me it was taken by her friend the Viennese photographer and social chronicler (“and probably spy” he adds!) Edith Tudor Hart who, Dan believes, also produced the equally striking portrait of Pearl on the Spitafields blog.

Pearl Binder died in 1990 aged 86: what a shame that the work of such a multi-talented and charismatic artistic figure is so rarely discussed or shown today. Someone who does keep her memory alive is her son, poet and rhyme-collector Dan Jones: I am indebted to him for his permission to reproduce the Christmas card from 1934, one of “the litho greetings prints that she continued to produce every Xmas for the next 50 years, come hell or high water…” says Dan, plus the striking photograph of his mother shown above: he tells me it was taken by her friend the Viennese photographer and social chronicler (“and probably spy” he adds!) Edith Tudor Hart who, Dan believes, also produced the equally striking portrait of Pearl on the Spitafields blog.