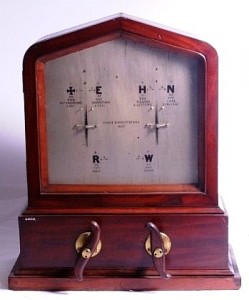

This view of soldiers in a trench on the Somme battlefront around Péronne was drawn by Victor Noble Rainbird, a local artist who fought with various battalions of the Northumberland Fusiliers during the First World War. His sketch shows a trench bell, set up to warn of gas attacks. Both sides in the war used gas – originally tear gas and subsequently mustard or phosgene gas. (There’s an eyewitness account of a gas attack on the Somme battlefield here.) Péronne is situated on a bend in the River Somme and was an important town in the war. It was absolutely devastated before its capture by the British army in March 1917, as can be seen in photos of King George V’s visit in July (photos here). Rainbird might also have been there in July when some Northumberland Fusilier battalions arrived on rubble-clearing duties. Others were at Péronne briefly in September. (Péronne is marked on a map showing the changing front lines on the Somme battlefront in early 1917 here, together with Arras, which was also part of Rainbird’s wartime story. There’s a map here of the Western Front battlefields in France and Belgium.)

This view of soldiers in a trench on the Somme battlefront around Péronne was drawn by Victor Noble Rainbird, a local artist who fought with various battalions of the Northumberland Fusiliers during the First World War. His sketch shows a trench bell, set up to warn of gas attacks. Both sides in the war used gas – originally tear gas and subsequently mustard or phosgene gas. (There’s an eyewitness account of a gas attack on the Somme battlefield here.) Péronne is situated on a bend in the River Somme and was an important town in the war. It was absolutely devastated before its capture by the British army in March 1917, as can be seen in photos of King George V’s visit in July (photos here). Rainbird might also have been there in July when some Northumberland Fusilier battalions arrived on rubble-clearing duties. Others were at Péronne briefly in September. (Péronne is marked on a map showing the changing front lines on the Somme battlefront in early 1917 here, together with Arras, which was also part of Rainbird’s wartime story. There’s a map here of the Western Front battlefields in France and Belgium.)

This sketch is one of a small group of Rainbird’s battlefield drawings currently on show in Paintings of World War 1 at the Laing Art Gallery until October 19th. The sketches, which seem to date from 1917 to 1918, open a window on Rainbird’s experiences and those of other North-East soldiers during the war. The drawings are tiny, sketched in a notebook the artist could carry in a pocket.

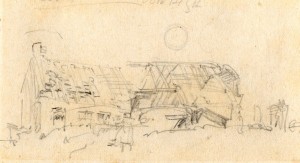

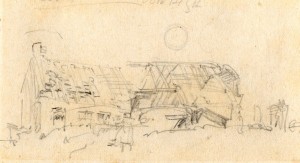

Rainbird titled this sketch Wancourt, Moonrise. It may show the ruined house on Wancourt Ridge alongside the tower (apparently the ruins of an old windmill reinforced with concrete), which had been a German observation and machine-gun post, causing a lot of trouble for British soldiers before it was captured in April 1917. The victorious soldiers were from Rainbird’s original Brigade (made up of the 4th, 5th, 6th & 7th Battalions of Northumberland Fusiliers) in the 50th Division. However, at the time, Rainbird himself was almost certainly at Arras, 7 miles further north, with the 34th Division (they arrived in Wancourt later). Francis Buckley of the 7th Northumberland Fusiliers described the battle, which took place in appalling weather:

Rainbird titled this sketch Wancourt, Moonrise. It may show the ruined house on Wancourt Ridge alongside the tower (apparently the ruins of an old windmill reinforced with concrete), which had been a German observation and machine-gun post, causing a lot of trouble for British soldiers before it was captured in April 1917. The victorious soldiers were from Rainbird’s original Brigade (made up of the 4th, 5th, 6th & 7th Battalions of Northumberland Fusiliers) in the 50th Division. However, at the time, Rainbird himself was almost certainly at Arras, 7 miles further north, with the 34th Division (they arrived in Wancourt later). Francis Buckley of the 7th Northumberland Fusiliers described the battle, which took place in appalling weather:

…about April 16 [actual date, April 15], 1917, Lieut.-Col. F. Robinson of the 6th N.F. discovered the enemy approaching the ruined buildings on the Wancourt Tower Hill, and promptly ordered a platoon to attack them. This plan succeeded admirably and the Tower and house were captured. The place was of vital importance to us as it commanded direct observation on all the roads leading to our part of the front. On April 17 the enemy shelled the Tower with 8-inch howitzers—generally a sign that he meant to attack sooner or later. The Tower contained a formidable concrete machine-gun emplacement, facing of course our way, but by General Rees’ orders it was blown up by the Engineers. Sure enough the enemy attacked the Tower that night, and at an unfortunate time for us, for the 7th N.F. were in the process of relieving the 6th N.F. in the front line, and it was a vile night, with a blizzard of snow.

The German attack succeeded in driving our men out of the Tower and buildings, and though several bombing attacks were made that night to recover the position it could not be done… next day…it was arranged to attack across the open supported by a barrage from five brigades of field artillery. The hour was fixed for twelve noon (German time) just when the enemy is thinking about his dinner. Without any preliminary bombardment, the barrage opened out at the appointed hour, and fairly drove the enemy off the hill top. The 7th N.F. advanced in perfect order and with little opposition recaptured the Tower and the neighbouring trenches….As this operation was carried out in full view of all the surrounding country it attracted considerable attention, and congratulations soon poured in from all sides.

Francis Buckley’s sketch, from his history of the 7th Battalion of Northumberland Fusiliers, shows the land around Wancourt and the tower. This is probably the kind of field observation drawings that Army Headquarters had sent Rainbird to make for the 34th Division Northumberland Fusiliers, who were in the centre of the Arras Offensive battlefront, near Arras itself. (The front extended south to Wancourt and Croisilles, and north to Vimy Ridge.) The troops would have needed sketch views marked with trenches, roads, hills, gun positions and other features. The ability to make views, rather than flat maps, would have been enormously helpful for soldiers to visualise the terrain they would be moving through. The army was able to print maps and plans in towns they held, like Arras, to supply to soldiers before important attacks. Rainbird was later congratulated for his drawings at Army Headquarters.

Francis Buckley’s sketch, from his history of the 7th Battalion of Northumberland Fusiliers, shows the land around Wancourt and the tower. This is probably the kind of field observation drawings that Army Headquarters had sent Rainbird to make for the 34th Division Northumberland Fusiliers, who were in the centre of the Arras Offensive battlefront, near Arras itself. (The front extended south to Wancourt and Croisilles, and north to Vimy Ridge.) The troops would have needed sketch views marked with trenches, roads, hills, gun positions and other features. The ability to make views, rather than flat maps, would have been enormously helpful for soldiers to visualise the terrain they would be moving through. The army was able to print maps and plans in towns they held, like Arras, to supply to soldiers before important attacks. Rainbird was later congratulated for his drawings at Army Headquarters.

Why had Rainbird moved from his original unit? During the war, some soldiers could find themselves moved around a lot, according to battle need. Rainbird apparently had Lewis gun skills and had already been separated from his first battalion to go to an anti-aircraft unit to protect the massive Zeneghem ammunition depot and canal/rail interchange, which was built in 1916, very close to Watten in France.

These soldiers at Wancourt are standing in front of the sandbagged entrance to a trench dugout (similar to the dugout illustrated on a BBC virtual tour of a World War 1 trench, here). As Rainbird noted in the title of the sketch, Wancourt was on the Hindenberg Line, which was originally a series of strong German defensive positions. The course of war brought the 34th Division Northumberland Fusiliers to Wancourt from early November 1917 to the end of January 1918. Rainbird had returned to these troops after special leave in England to take part in a military memorial plaque design competition, sometime during the competition period of mid August to the end of December 1917.

These soldiers at Wancourt are standing in front of the sandbagged entrance to a trench dugout (similar to the dugout illustrated on a BBC virtual tour of a World War 1 trench, here). As Rainbird noted in the title of the sketch, Wancourt was on the Hindenberg Line, which was originally a series of strong German defensive positions. The course of war brought the 34th Division Northumberland Fusiliers to Wancourt from early November 1917 to the end of January 1918. Rainbird had returned to these troops after special leave in England to take part in a military memorial plaque design competition, sometime during the competition period of mid August to the end of December 1917.

The relatively quiet time the Northumberland Fusiliers were having at Wancourt came to an end in March 1918, when the Germans launched a major offensive to retake the Somme area. Rainbird took part in fighting at St Leger, near Wancourt. He then moved north with the 34th Division to Armentières, near the River Lys, in the French Flanders region adjacent to Belgium. The Division lost thousands of soldiers killed or wounded in these battles. In a huge German gas and explosives attack on Armentières, Lieutenant John Shakespear, author of the 34th Divisional history, recorded that from gas alone, “we had about nine hundred casualties. Two companies of 25th Northumberlands … were practically all gassed”. The British front line troops were forced into a withdrawal, described by Lieutenant Shakespear:

I don’t think that anyone who was concerned that night’s operation will ever forget it. The troops had been engaged heavily for three days and nights, and had suffered heavy losses. The night was very dark, detailed maps were scarce, the positions alike of friends and foes were very uncertain and were constantly changing. The plan of retirement was for the 101st, 102nd, and 103rd Brigades to retire by the Armentières-Bailleul railway and road… The enemy barraged the railway so heavily that the troops had to leave it and find their way across country in small parties…

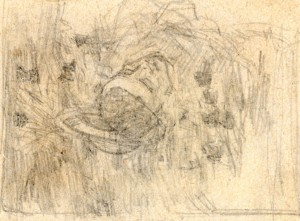

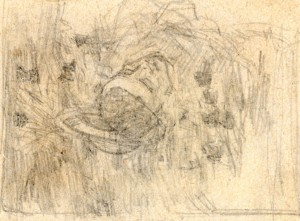

After moving in April to St Jans Cappel on the border with Belgium, the troops of the 34th Division found themselves almost immediately in the middle of another battle, to try to prevent the Ypres area being overrun and protect the route to Dunkirk and the other French Channel ports. Thousands of British soldiers fell on the battlefield at this time, like the soldier in this sketch, who lies surrounded by poppies. The German troops also suffered severe losses.

Rainbird titled this sketch Poppies (from a shell hole). It was often impossible to bury dead soldiers immediately after a battle, and huge numbers lay on the battlefields until they could be reached. Poppies bloomed there from April (if the weather was warm) to September. The shelling of the war churned up the earth, releasing the poppy seeds, so that the battlefields were covered in poppies, and the flower has become the symbol of the sacrifice of the wartime soldiers.

Rainbird titled this sketch Poppies (from a shell hole). It was often impossible to bury dead soldiers immediately after a battle, and huge numbers lay on the battlefields until they could be reached. Poppies bloomed there from April (if the weather was warm) to September. The shelling of the war churned up the earth, releasing the poppy seeds, so that the battlefields were covered in poppies, and the flower has become the symbol of the sacrifice of the wartime soldiers.

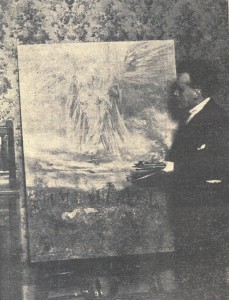

Rainbird’s little pencil sketch of the dead soldier on the battlefield is linked to a painting he produced in 1930, revealing the continuing impact the war had for him, even 12 years after it ended. In the photograph, Rainbird is posing with his painting, All Quiet on the Western Front, which was illustrated in the Shields Daily News of 7th May 1930 (reproduced courtesy North Shields Local Studies Centre). It’s difficult to see all the details as newspaper photographs of the time were not very high quality, but the caption gives interesting information:

Rainbird’s little pencil sketch of the dead soldier on the battlefield is linked to a painting he produced in 1930, revealing the continuing impact the war had for him, even 12 years after it ended. In the photograph, Rainbird is posing with his painting, All Quiet on the Western Front, which was illustrated in the Shields Daily News of 7th May 1930 (reproduced courtesy North Shields Local Studies Centre). It’s difficult to see all the details as newspaper photographs of the time were not very high quality, but the caption gives interesting information:

At a special interview granted to a “Shields Daily News” representative Mr. Rainbird said the idea for the title of his picture was gathered from the oft repeated phrase in Earl Haig’s official communiqué, “All Quiet on the Western Front”. The picture… portrays a soldier of the 5th Battn. Northumberland Fusiliers killed in action lying amidst the barbed wire entanglements and Flanders poppies. Mr. Rainbird used his own likeness as a model for the soldier, and his own regimental number is on the gas mask on the soldier’s breast. The dead soldier’s likeness to the artist is remarkable. The whole picture is an expression of what Mr. Rainbird actually saw at the last battle of the Somme. In the background we can see the barrage slowly creeping over “No Man’s Land”. The soldiers have gone on ahead, leaving their fallen comrade behind, while from the clouds we have gazing down three Angels of Peace on “All Quiet on the Western Front”.

After the enormous losses suffered by the 34rd Division in late 1917 and early 1918, the remaining troops were withdrawn from fighting. They spent a few weeks building a new defensive line close to Poperinge, near Ypres, in Belgium. Then, in mid May, Rainbird moved with the remnants of the 34rd Division to near Lumbres, south of Calais. There, he was involved in training American shock assault troops in the use of the Lewis gun. He was in England for officer training when the war ended in November 1918. After this, Rainbird returned to his home town of North Shields to pick up his career as an artist, exhibiting at the Laing Art Gallery and elsewhere. Sadly, he apparently developed a drink problem, possibly linked to his wartime experiences. He died at the age of 49.

Sources and related information

Victor Noble Rainbird Obituary, Shield Daily News, March 9th 1936, copy in the Victor Noble Rainbird folder at North Shields Local Studies Centre, North Shields Library.

WW1 Battlefields of the Western Front

Victor Noble Rainbird Wikipedia page

The changing battlefronts following the German withdrawal to the Hindenberg Line in 1917 is shown here, with Arras and Péronne marked.

The History of the Fiftieth Division 1914-1919. By Everard Wyrall, 1921

The History of the Thirty-Fourth Division 1914-1919. By Lieut.-Colonel John Shakespear, 1921. (One of the illustrations is a sketch view by Major Vignoles, showing military features in the landscape for a forthcoming attack. Perhaps Rainbird contributed field observations for this sketch.)

King George V at Péronne, July 1917, The Royal Visits To The Western Front, 1914-1918

First World War Official Photographs

British troops crossing the Somme into Péronne, March 1917

British troops watching shelling at Wancourt

The daily routine of front line service, Imperial War Museum online

Gas Attack, 1916, The Somme, Eyewitness History online

Dug-out Entrance Virtual Tour, BBC online

Photograph of an officer, sargeant and private soldier of the Northumberland Fusiliers in World War 1

Photograph of British soldiers in tents in a mine crater on the Somme

The Project Gutenberg EBook of ‘Q.6.a and Other places, Recollections of 1916, 1917 and 1918’ by Francis Buckley, eBook (history of the 7th Battalion of Northumberland Fusilers)

Northumberland Fusiliers War Diaries (microfiche) Local Studies, Newcastle City Library; & the National Archives

The War Diary of the 1/7th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers

April 1915 – January 1918

The 4th Battalion of Northumberland Fusiliers. Gives research resources, etc