Recently, one of our visitors has shown us some interesting First World War drawings by his grandfather, Private James McGarrigle. A coal miner at Seaton Delaval before he joined up, Private McGarrigle was a soldier with 7th Northumberland Fusiliers Observation Corps throughout the war. He wasn’t a trained artist, but the sketchbook he kept during the war gives us a picture of life in the trenches as ordinary soldiers experienced it.

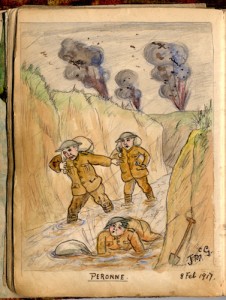

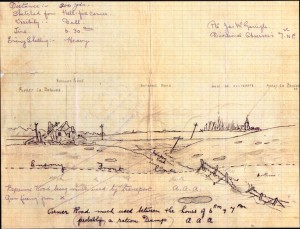

Soldiers tried to keep their spirits up with humour. A photo (here) shows the reality of the River Somme system around Péronne in 1917 – Private McGarrigle drew his sketch just a month before the town was taken by the British army in March 1917, following German occupation.

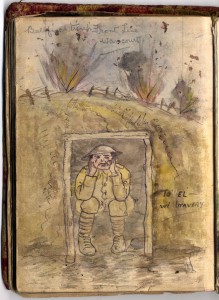

McGarrigle’s humour is a bit darker in this sketch – “To ‘El wi’ bravery”, he’s written on the picture, showing a soldier weeping in his dugout as the bombs explode around him. At the top of the drawing, McGarrigle noted that the sketch showed a new trench that the soldiers were building at Wancourt. A lot of fighting took place around Wancourt, near Arras, in 1917 and 1918, and there’s a photo here. McGarrigle’s experiences must have been fairly similar to those of Northumberland Fusilier Victor Noble Rainbird, whose sketchbook drawings are in our collection (previous post, here). Rainbird was also at Péronne and Wancourt, though not at the same time as McGarrigle.

Although McGarrigle has used a comic style for this drawing, the subject is anything but humorous. He’s titled it, “Twas a night I’ll ne’re forget as long as I may live”. He’s shown a soldier clinging to a mule while another mule tries to turn back in alarm. The supplies of Stokes mortar bombs they’ve been carrying lie scattered on the ground. McGarrigle may have been picturing the pack mule track to the area named Tyne Cottages at Passchendaele, where the 7th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers were operating in late 1917. The battalion historian, Captain Francis Buckley, mentions the dead pack mules on the track and the awful mud of at Passchendaele.

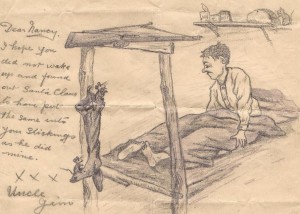

One Christmas, Private McGarrigle sent his niece a sketch of rats in his sleeping area on Christmas morning, saying, ‘I hope … Santa Claus [did not] put in your stockings the same as he did mine.’

One Christmas, Private McGarrigle sent his niece a sketch of rats in his sleeping area on Christmas morning, saying, ‘I hope … Santa Claus [did not] put in your stockings the same as he did mine.’

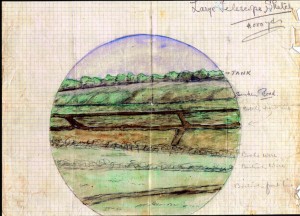

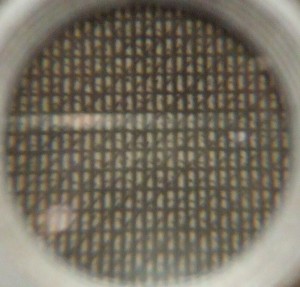

Private McGarrigle’s duties in the Field Observation unit involved making sketches of the countryside and the front lines so the unit commanders could plan for action. This drawing shows the view through a telescope with a tank position and barbed wire lines marked. Much of the observation work was done under cover of darkness. In an interview with James McGarrigle in 1938, the Blyth News & Ashington Post reported that, ‘many were the nights when he and Capt. Francis Buckley used to crawl beyond the lines and sketch the “lay of the land.” The information collected in that way … proved of great use to the Allies’.

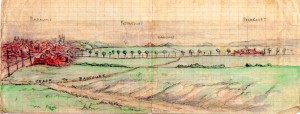

This sketch shows the ruined town of Bapaume on the left. Bapaume had been badly damaged in March 1918 during the German offensive to retake the Somme area. It was retaken by the British army in September along with Riencourt, which is also marked on the map. The 7th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers were here for a few weeks in September, as Francis Buckley’s history of the battalion records.

Bapaume also features in this map, on the left, with a sunken road leading to the town, and observations noted on the drawing. Buckley recorded in the battalion history, ‘At dawn on September 28 [1918] the grand assault on the Hindenburg Line began….McGarrigle went to the O.P. [observation post] in the front line on September 28 and had rather a rough passage.’ Later, the battalion moved on to near Viesly. Francis Buckley noted that ‘McGarrigle made a useful sketch of the view in front.’ Conditions were dangerous for the observers – Buckley recorded, ‘Our only cover was a shallow trench about one foot deep; and for an hour whilst I was trying to sketch the details of the landscape the enemy’s 4.2-inch howitzers shelled the hill persistently.’ Buckley was responsible for bringing all the information in the observers’ sketches together, and then using them ‘to make a drawing of the panorama in front, which was printed out for the use of the troops in the line.’

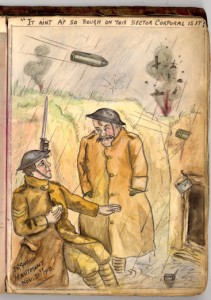

The two soldiers in this drawing are up to their calves in water in the trench as bombs fly overhead. It’s ironically titled “It ain’t a’f so rough on this sector Corporal is it”. At the bottom McGarrigle’s written the note “Hautmont November 21st 1918”. The 7th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers were near Hautmont in France when the Armistice was declared on 11th November 1918. McGarrigle’s battalion must still have been in the area on the 21st, and his humorous image presumably records conditions just before the war ended.

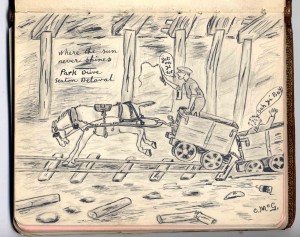

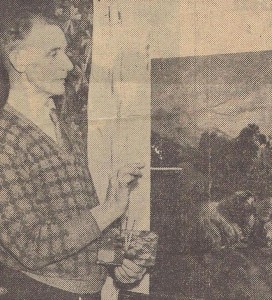

After the war, James McGarrigle returned to the mine at Seaton Delaval. This drawing of a pit pony down the mine is signed with the initials of his brother Charles, who was also a miner and an artist. The two shared a cottage. The mine sketch probably dates from before the war, as the page next to the drawing in the sketchbook is dated 1916. The waggon driver seems to be wearing his safety lamp around his neck. James McGarrigle carried on with his painting in his spare time. He told the Blyth News & Ashington Post reporter, “If I am busy with a painting in such a week as this when I don’t come in from work until after tea, I spend the evenings putting in the ‘bottom’ [base layers of paint] and I leave the real colour work until Saturday”, so that he would have daylight to blend the oil colours properly.

After the war, James McGarrigle returned to the mine at Seaton Delaval. This drawing of a pit pony down the mine is signed with the initials of his brother Charles, who was also a miner and an artist. The two shared a cottage. The mine sketch probably dates from before the war, as the page next to the drawing in the sketchbook is dated 1916. The waggon driver seems to be wearing his safety lamp around his neck. James McGarrigle carried on with his painting in his spare time. He told the Blyth News & Ashington Post reporter, “If I am busy with a painting in such a week as this when I don’t come in from work until after tea, I spend the evenings putting in the ‘bottom’ [base layers of paint] and I leave the real colour work until Saturday”, so that he would have daylight to blend the oil colours properly.

Maybe one of your relatives was involved in the Great War and you have information or photos you’d like to share? You can share your family First World War stories with the world on these websites – Lives of the First World War & First World War Centenary history pin. You may also be interested in these local websites – Durham at War & Sunderland in the First World War. Information about Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums’ First World War project can be found here – Wor Life : Tyne and Wear in the First World War & worlife1914.tumblr.com.